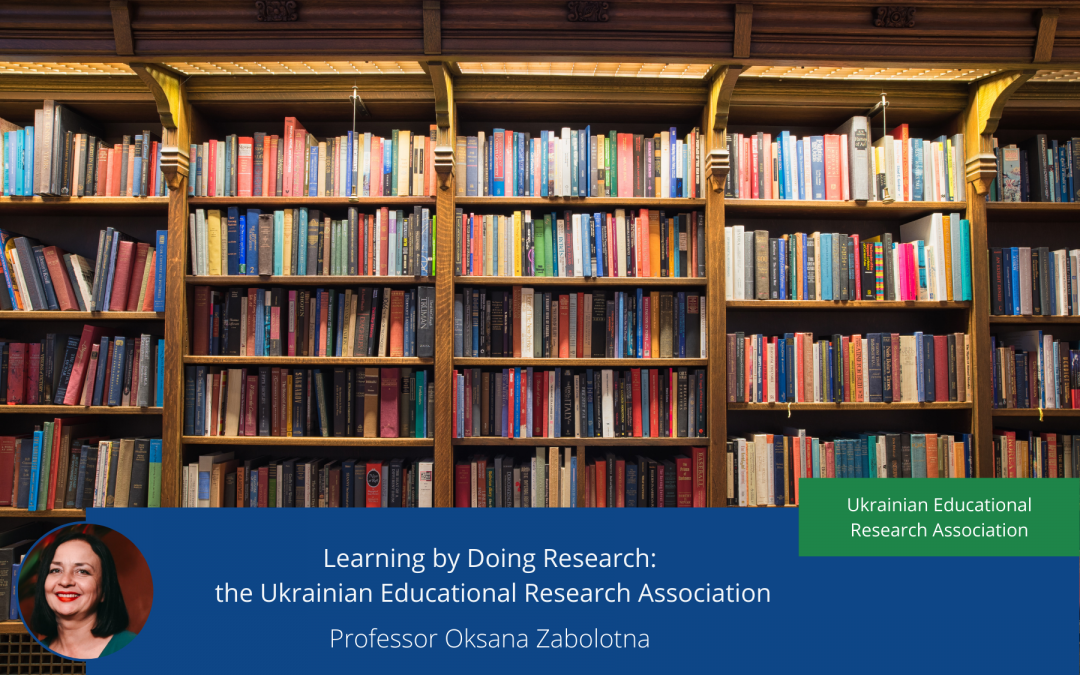

Refugees and Education – Voices, Discourses and Policies

The issue of refugees and asylum worldwide is a topical debate, where statistics and states play a major role with regard to research. Research focuses almost exclusively on the now, on themes like borders, trafficking, and human rights. In Europe in particular, the years 2015 and 2016 marked a turning point, because the numbers of refugees who arrived and applied for asylum reached the highest level in the Post-World-War II era. The so-called ‘refugee crisis’ underlines the necessity to integrate the incomers into established communities. This is, however, not a new phenomenon.

In political discourses and other actual debates around the entry, asylum process, and integration of refugees, historical comparisons to argue against refuge or to raise empathy are commonly used.

Why historical research of refugees matters for present policy decisions

From an educationalist view, there is an urgent need to historicize the topic of forced migration to improve our understanding of the present age of movement. Europe has a long history of refugees and providing asylum and nation-states were the main actors in making refugees in the 20th century. The reason why we inquire about the relation between present and past in discourses about refugees and providing asylum is that our frames of reference are coined by this history. We would like to give voice to the experiences of violence. Throughout history nations received refugees, schools have a long history in receiving traumatised children and still are often left helpless with regard to personnel, materials, etc. And each time the public discourse only seems to focus on the now, the new, the particular.

Reconnecting EERA Online Conference – Refugees and Education throughout Time in Europe

During ‘Reconnecting EERA’ NW 07 Social Justice and Intercultural Education and NW 17 Histories of Education hosted a number of sessions in conjunction with the special call “Refugees in/and Education throughout Time in Europe: Re- and Deconstructions of Discourses, Policies and Practices in Educational Contexts”.

Anke Wischmann of Europa-University Flensburg, Germany, and Susanne Spieker of University Koblenz-Landau, Germany initiated the call. The aims of our joint call were: to bring the history of refugee-immigration into focus; to highlight continuities as well as changes; and to understand refuge not only as a single event, but also in a historical context, with particular discourses and practices around education, and as an inter-generational social process, which sees migrants as actors transforming education in states. This call was quite successful, as 25 abstracts were submitted.

On 26th August 2020, Network 17 organised a series of three informal sessions. In the 2nd session, Susanne Spieker (presenting) and Anke Wischmann introduced the special call and historical research on refugees. We discussed ideas, sources, and approaches for historical research on refugees and forced migration. For example, we looked at the problem of complexity concerning the history of refugee movements. These histories need to be transnational and global. They have to take into account the voices of refugees themselves as well as the practitioners working with them. For historical research, the accessibility to experiences is related to historical sources such as letters.

On 26th August 2020, Network 17 organised a series of three informal sessions. In the 2nd session, Susanne Spieker (presenting) and Anke Wischmann introduced the special call and historical research on refugees. We discussed ideas, sources, and approaches for historical research on refugees and forced migration. For example, we looked at the problem of complexity concerning the history of refugee movements. These histories need to be transnational and global. They have to take into account the voices of refugees themselves as well as the practitioners working with them. For historical research, the accessibility to experiences is related to historical sources such as letters.

Time perception is another aspect, which seems to make historical research on forced migration challenging. For instance, if one asks or reads documents from different age groups about the same event, grandparents or parents, small children or adolescents have their own perceptions of the same situation. Each age group will offer a different view.

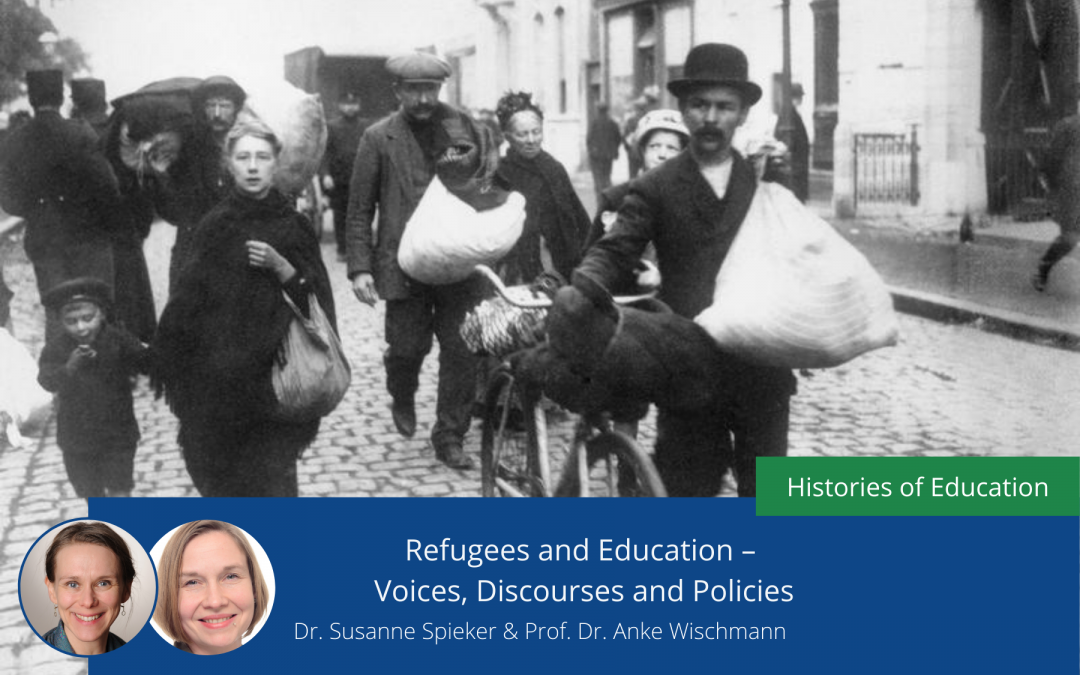

Family migration is common, as visualised in the above copper engraving from 1698, which depicts Huegenots leaving France. Women and children are a marginalised group with regard to migration in general because former research presumed that mainly men migrate. The opposite is the case. As these families travelled, skills and handicrafts, religious ideas, and educational approaches spread across Europe. These individuals were also actors in the education of their children.

On August 27th, 2020, both networks cooperated in holding a virtual forum. Fourteen individual papers were presented in four parallel sessions. The regional focus of presentations ranged from Denmark to Namibia and from France to Australia. The presentations in the first two break-out sessions covered a range of topics, such as the practical experiences of adolescent refugees and participants of higher education and vocational education in Poland, Bangladesh, and New Zealand, to the empowerment of women from ethnic minority backgrounds in various European countries.

Another break-out session presented and discussed different approaches and experiences with Unaccompanied Minors (UAM) arriving in France and Italy in recent years. Researchers shared their experiences with various educational approaches, and the challenges children and adolescents face.

The second set of parallel sessions introduced school practices and captured the voices of practitioners. In another session, presenters shed light on hidden curricula by analysing exclusionary practices experienced by Ju|’huan students in Namibia, representations of refugees in Polish children’s literature, and a Latvian Gymnasium and its history in the context of the cold-war in Western Germany.

There were many parallels noticed with regard to the seemingly unique experiences that refugees and minorities face in different regional settings. We realised that the complexity of the topic united quite a broad spectrum of methodological approaches, which we found inspiring. However, linking history and present-day research is not evident at first sight.

The responses to the presentations were engaged and positive. In the closing session, researchers valued the opportunity to reconnect, which for most of us was badly needed, due to the restrictions related to the COVID-19-pandemic. We decided to organise a new special call for the Geneva (online) ECER, with a slightly broader scope. We will keep you posted!

In addition to the initiators, the following members assisted with the organisation, planning, and implementation: Lisa Rosen (Link-convenor of NW 07) and Iveta Kestere (Link-convenor of NW 17). Throughout the two days sessions were chaired by Klaus Dittrich (Hong Kong), Geert Thyssen (Norway), Iveta Kestere (Latvia), and Lisa Rosen (Köln). Fenna tom Dieck (Köln) supported us with Zoom.

Dr. Susanne Spieker

Substitute Professor at the department for educational theory, intercultural and comparative education at Hamburg University

Susanne Spieker is currently a substitute professor at the department for educational theory, intercultural and comparative education at Hamburg University (Germany). She is a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Koblenz-Landau, Campus Landau in the research unit on Heterogeneity in education. Her research expertise lies in the history of education. She has published on colonialism and its impact on educational thought. Her research interests include migration and inequality in education (race/ethnicity, gender, class). She was a member of the Editorial Assistant Board (2017 – 2018) of Paedagogica Historica, International Journal of the History of Education, and serves as an external reviewer for History of Education Researcher (UK) and Paedagogica Historica. Since 2016 she is editor of the Journal Jahrbuch für Pädagogik.

Prof. Dr. Anke Wischmann

Professor for Education at the Europe-University Flensburg

Anke Wischmann is a professor for education at the Europe-University Flensburg (Germany). Her research focuses on social justice in education, in particular concerning race and ethnicity, analysed from a critical and qualitative perspective. She got her Ph.D. in 2010 at the University of Hamburg and her habilitation in 2017 at Leuphana-University in Lüneburg. In 2018 her article “The absence of race in German discourses on Bildung” won the emerging researcher award of the German Educational Research Association (GERA). Since 2016, she has been the editor of the Journal Jahrbuch für Pädagogik.