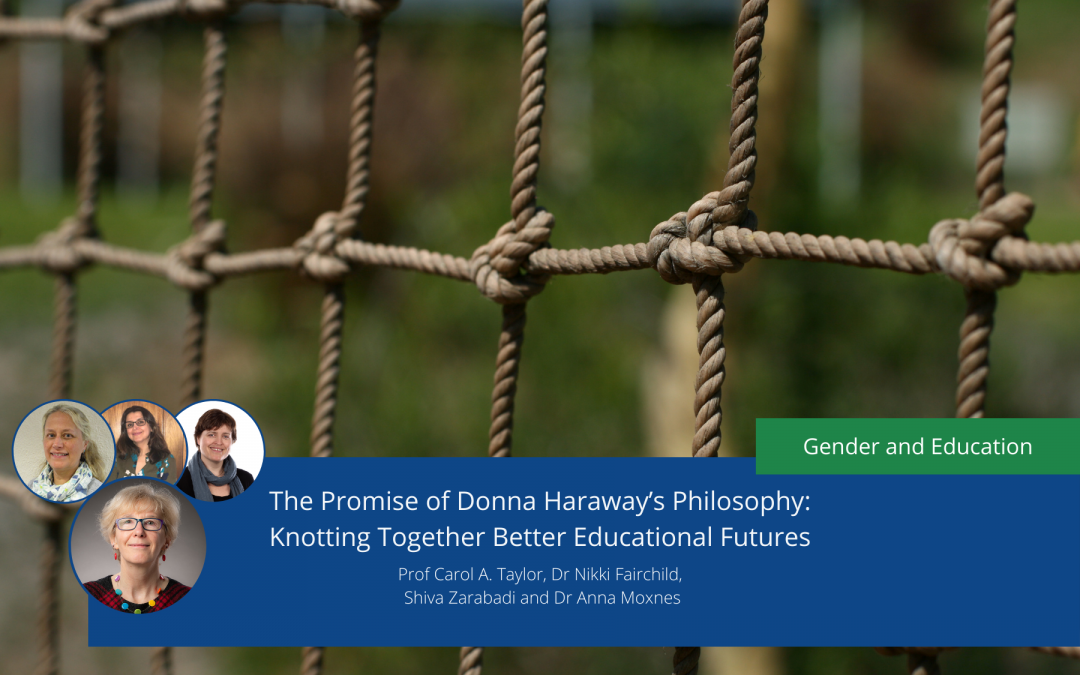

The Promise of Donna Haraway’s Philosophy: Knotting Together Better Educational Futures

As we have grappled with critical questions in our research and teaching, all of us contributing to this blog have been energised by Donna Haraway’s work. This blog explores the promise of Haraway’s philosophy for knowledge, learning and education. Donna Haraway’s philosophy offers conceptual and practical resources for navigating the complexities of contemporary educational problems.

Reconceptualising knowledge, learning and education with Donna Haraway

Haraway’s major early intervention was to challenge traditional notions of objectivity – which she called ‘the God trick’ (Haraway, 1988). She argued that objectivity was a Western masculinist, patriarchal tradition, which presumed researchers could be impartial, observe and produce ‘Truth’. This damaging fallacy has conferred epistemological status on science delegitimizing many other ways of knowing. Haraway opposes ‘the God trick’ with the concept and practice of ‘situated knowledges’ which pose a feminist critique demonstrating that knowledge practices are ‘political’ and that some knowledges have been (illegitimately) disqualified by dominant science. Recognising that all knowledge is located and relies on partial perspectives allows for the inclusion of lived material realities and feelings that shape our educational experiences.

The concept and practice of learning is central to Haraway’s oeuvre. Learning happens in the world, attending to our being-in-relation with the world and other species. Learning is an enactment: she calls it a ‘corporeal cognitive practice’ (Haraway, 2016a: 277), a material semiotic co-composition of relational acts of thinking and doing. Learning comes about through specific, mundane, embodied acts of communication that forge partial connections across the differences (of race, class, geography or species) that divide us.

Haraway’s philosophy, and its promise for education, demonstrates the need to move beyond human exceptionalism. It is an urgent call for us to take responsibility for how humans have produced alarming natural-cultural conditions, and to take action to address these. The task of shaping better human/planetary futures has been recognised as core to education as an ethical-political project (Strand, 2020). Haraway’s philosophy offers an affirmative biopolitics that can be useful in extending curricula on global education (Barratt Hacking and Taylor, 2020). Her transdisciplinary thinking, feminist situated ethics, and situated politics of knowledge might be the basis for renewing educational approaches for composing more relational futures.

How has Haraway’s philosophy been influential in our research?

Carol has taken up Haraway’s philosophy outlined in When Species Meet (2008) to rethink what comes to matter in educational relations. Her work addresses the question: How can multispecies knowings and matterings give us hope to build a better world for the future? Haraway (2008: 134) uses multispecies thinking to argue for ‘compassionate action’ to promote well-being for individuals, species and communities. Carol has considered how such thinking can be the foundation for different forms of educative flourishing by fashioning education as a form of posthuman Bildung that bring new possibilities for knowledge/praxis (Taylor, 2016). Carol has also considered how nonhuman-human relations can centre around play and pleasure in ways which make consequential differences in our lives as academics (Taylor, 2017).

Nikki (Fairchild, 2017) has drawn on The Cyborg Manifesto (1991) to reconceptualise young children’s gender identities. Haraway uses the cyborg both as figuration and ontological position to explore the breakdown and fluidity of technological, natural and cultural bodily boundaries. Nikki’s research shows how the cyborg figuration ‘moves beyond traditional notions of the feminine body’ (Benozzo et al., 2019: 89). Her doctoral thesis considered how girls are expected to perform and act in certain ways (Fairchild, 2017) and how the cyborg can ‘produce[s] new articulations of gender at the same time as making traditional gendered societal roles ‘available’’ (Taylor & Fairchild, 2020: 520). The cyborg subverts gender and provides new political possibilities for women.

In Staying with the Trouble, Haraway posits ‘lived storying’ (2016b: 150) as ‘the most powerful practice for… becoming-with each other’. Shiva has written of co-storytelling as a way of making-together, co-theorizing and co-enduring (Niccolini, Zarabadi & Ringrose, 2018). Lived storying foregrounds the care-full response-ability required when researching participants’ experiences. Towards the end of her PhD thesis writing, the COVID pandemic put the world into multiple lockdowns and made racism intelligible in new ways. Shiva’s PhD participants are from British Bangladeshi backgrounds, they live in overcrowded households and, like other BAME populations, suffer disproportionate social and educational inequalities (Booth, 2020). Their COVID storyings speak of histories of exclusion, troubled times and uncertain futures.

‘No adventurer should leave home without a sack’ writes Haraway (2016b: 40) in Staying with the Trouble. Haraway learned about the carrier bag theory of storytelling from Ursula Le Guin (1989). During her PhD, Anna experimented with a Bag-lady positionality (Moxnes, 2019), figuring herself as an (elderly) woman collecting whatever she found carrying everything with her in bags. For Anna, the carrier bag theory became a story of research, a methodological and methodic concept, a feminist force enabling her to do research differently. Carrier bag research provides a compass ‘to think otherwise’ – it changes our understandings of the world we live in and how we make meaning about it.

In our work together, Haraway’s philosophy gives us the courage to find philosophical and practical ways of troubling dominant educational thinking, research and writing (Zarabadi et al., 2019). Haraway’s philosophy informs our collaborative research experiments in theory, method and practice enabling us to continue to think of new ways to produce academic knowledge differently.

Some Final Thoughts

Haraway’s books are not easy, but they repay the focus, immersion and concentration needed. Haraway makes you think about how you can do research and teaching differently and in more creative ways. Her writing is an encouragement to slow down, ponder, not rush to action too quickly, and to focus on details and specificities. She offers intellectual resources to contest neoliberal imperatives of competitive individualism, performativity and measurement. Haraway’s philosophy provides a stimulus to new, creative, experimental ways of producing knowledge; her generative, ecological, life-affirming thinking offers important insights for reshaping educational thinking to contest the damages of the Anthropocene.

Citations and Further Reading

Situated Knowledges: The Science Question in Feminism and the Privilege of Partial Perspective – Haraway, 1988

Situated Knowledges – Monika Rogowska-Stangret

Manifestly Haraway – Haraway, 2016

Rethinking Ethical-Political Education – Strand, Torill

Reconceptualizing international mindedness in and for a posthuman world – Barratt Hacking and Taylor, 2020

When Species Meet – Haraway, 2008

Is a posthumanist Bildung possible? Reclaiming the promise of Bildung for contemporary higher education – Taylor, 2016

Producing Pleasure in the Contemporary University – Taylor, 2017

Earthworm disturbances: the reimagining of relations in Early Childhood Education and Care – Fairchild, 2017

Simians, Cyborgs, and Women (The Cyborg Manifesto) – Haraway, 1991

Disturbing the AcademicConferenceMachine: Post‐qualitative re‐turnings – Benozzo et al., 2019: 89

Towards a posthumanist institutional ethnography: viscous matterings and gendered bodies – Taylor and Fairchild, 2020

Staying with the Trouble – Haraway, 2016

Spinning Yarns: Affective Kinshipping as Posthuman Pedagogy – Niccolini, Zarabadi & Ringrose, 2018

BAME groups hit harder by Covid-19 than white people, UK study suggests

Dancing at the Edge of the World – Ursula Le Guin

Working Across/Within/Through Academic Conventions of Writing a Ph.D.: Stories About Writing a Feminist Thesis – Moxnes, 2019

Feeling Medusa: Tentacular Troubling of Academic Positionality, Recognition and Respectability – Zarabadi et al., 2019

Authors

Professor Carol A. Taylor

Professor of Higher Education and Gender in the Department of Education, University of Bath

Professor Carol A. Taylor is Professor of Higher Education and Gender in the Department of Education at the University of Bath where she is Director of Research and leads the Learning, Pedagogy and Diversity Research cluster. Carol’s research focuses on the entangled relations of knowledge, power, gender, space and ethics in higher education and utilizes trans- and interdisciplinary feminist materialist and posthumanist theories and methodologies. She is currently exploring the relations between feminist praxis and quiet activism, women’s academic leadership and mentoring, and institutional power. She is engaged in various experiments in doing academic writing differently. Carol is co-editor of the journal Gender and Education. Her latest books are Taylor, C. A., Ulmer, J., and Hughes, C. (Eds.) (2020) Transdisciplinary Feminist Research: Innovations in Theory, Method and Practice. London: Routledge and Taylor, C. A. and Bayley, A. (Eds.) (2019) Posthumanism and Higher Education: Reimagining Pedagogy, Practice and Research.

Dr Nikki Fairchild

Associate Head (Research and Innovation), School of Education and Sociology, University of Portsmouth

Dr Nikki Fairchild is Associate Head (Research and Innovation), School of Education and Sociology, University of Portsmouth. Her research interests include posthumanist and material feminist theorizing to articulate more-than-human subjectivities in Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC). Her recent research centres on place/space in classrooms and gardens, this has been enacted using walking-with methodologies. She is also part of any International collective which challenges the knowledge practice in conference spaces. The collective enacts arts-based research-creation workshops at conferences to consider how human, non-human and other-than-human bodies interact. The collective has recently been awarded a Special Commendation for the BERA Anna Craft Creativities in Education 2020 Prize.

Shiva Zarabadi

PhD research candidate at UCL Institute of Education

Shiva Zarabadi is PhD research candidate at UCL Institute of Education. Her research interests include feminist new materialism, posthumanism and intra-actions of matter, time, affect, space, humans and more-than-humans. In her PhD she uses walking and photo-diary methodologies to map these relational materialities. She is the co-editor of the book Feminist posthumanisms/ new materialisms and Education (Routledge 2019) and the leading author of the journal article “Feeling Medusa: Tentacular troubling of academic positionality, recognition and respectability” (2020) in Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, and chapters “Post-Threat Pedagogies: A Micro-Materialist Phantomatic Feeling within Classrooms in Post-Terrorist Times”(2020) in Mapping the Affective Turn in Education Theory, Research, and Pedagogies, “Re-mattering media affects: pedagogical interference into pre-emptive counter-terrorism culture” in Education Research and The Media(2018) and a co-authored article ‘Spinning Yarns: affective kinshipping as posthuman pedagogy in Parallax(2018).

Dr Anna Moxnes

Associate Professor at the department of Pedagogy, University of Southeastern Norway

Dr. Anna R. Moxnes is an Associate Professor at the Department of Pedagogy at the University of Southeastern Norway. Anna’s research interest is feminism and new materialist perspectives. Her recent projects involve both higher education and early childhood practices, including children and animals, and children and aesthetics, in Early Childhood Education and Care institutions, but also classroom teaching and materiality in Early Childhood Teacher Education ECTE) and research connected to education of mentors for students in teacher education. These research interests brought her in contact with international researchers, which have expanded her professional network and her writing experiences. Right now, she is co-editing a book about research-projects in ECTE in Norway. In 2019, she was honored with a Norwegian national prize for teaching.