For some time now, I have been eager to share my thoughts on how transactional language has infiltrated the discourse of educational reform and associated continuing teacher education. I refer specifically here to how the terminology of related policy has adopted a rather corporate flavour, mimicking patterns of the economic and business world. In the Teaching and Learning International Survey ( OECD, 2018) this ‘resignification of educational language’ (Flubacher & Del Percio, 2017, p. 7) was difficult to ignore. Populated by phrases such as ‘cost effective mechanisms to deliver professional training ‘( p.160) and ‘individual teacher performance in the workplace’ (p. 156), the word ‘indicators’ appears no less than 69 times.

Here in Ireland, recent policy to guide ambitious reform efforts which are aimed at upper secondary education (Department of Education and Youth, 2025) uses the term ‘delivery’ when describing the teacher professional development and learning to support the reforms. The same document is peppered with the term ‘tranche’ in reference to an incremental “roll out” of revised subjects. Notably the Oxford dictionary defines tranche as ‘a financial instalment’ with Investopedia describing tranches as ‘segments of a whole divided up to be more marketable to investors’.

Neoliberalism made us do it!

We should not be surprised that this transactional tenor has infiltrated education policy speak. Since the 1990s, Europe, like much of the western world, has succumbed to the marketisation of education as a competitiveness resource (Sahlberg, 2012) wherein education policy is frequently characterised by successive action plans, target setting and frantic timelines. Cue a distinct catalogue of what Hood (1995, p. 105) once described as ‘new managerial catchwords’ enshrined in a ‘new global vocabulary’ for education. An analogous critique below of three such catchwords often used in the context of education reform and continuing teacher development, attempts to highlight their unsuitability for the sphere of education.

DELIVERY – Quality professional development and learning for teachers during periods of reform is not a ready- made product that travels by courier from some warehouse of ‘packages’ for recipient teachers to unwrap on its arrival. The corpus of research ( Timperley et al., 2007) and direct experience has long shown that knowledge and learning is constructed by the self-identified needs of teachers informed by those of their young learners. Skilful facilitation and dynamic exchange realises this potent process where teachers become the knowledge constructors and shapers of policy, as opposed to mere consumers of that created by others.

ROLL-OUT – Quality professional development and learning is not a vaccine injected en masse into our teacher population during periods of reform ‘…to pep them up, calm them down, or ease their pain’ (Hargreaves, 1994, p.430). Framing it in this way suggests a national marshalling of ‘one shot’ remedies to protect them against the next wave of ‘viral’ reform.

TRAINING – With no disrespect to the process of training in its appropriate context, teacher professional development and learning is not a technical endeavour operated by PowerPoint saturation and rehearsed scripts. The purpose of continuing teacher education is not to ‘indoctrinate’ teachers (Gibbons et al., p.1994) using standard slideshows, but to craft an environment where teachers as thinking professionals navigate complex dilemmas and make sense of reforms according to their unique schools and classrooms.

Deeply pervasive yet unnoticed

I’d like to emphasise here that there is nothing inherently wrong with this kind of terminology. However, it becomes problematic when crudely applied to the messy nature of educational reform and the equally uneven but richly reflective process of teacher development and learning. The voice afforded to this ‘uneducational’ terminology has been amplified with the advent of unprecedented reform associated with the aforementioned subordinance to neoliberal doctrine policy.

Ironically, the big idea of teacher agency is presented as a rationale across many of these current reforms. In this case however , we see teacher agency manifesting at the level of discourse where it is arguably restricted through an uncontested lexicon of reductive terms. Research into teacher agency (Priestley, Biesta & Robinson, 2015) shows that many teachers already overwhelmed by the volume of change simply adopt the language of the latest policy without critically questioning what that language suggests, or how it colours perceptions of who teachers are, what they do and how they learn best.

‘Be kind to our language while alert to how we use particular words and to how words use us’

Timothy Snyder

Snyder (2016, p.59) reminds us that the language we adopt constructs and constrains the meaning applied to reality. It is, therefore, more than just a matter of words which themselves ‘are not some kind of decorative wrapping paper in which meaning is delivered’(Collini 2017, p. 3), but of powerful neoliberal undercurrents steering our thinking and behaviours with important implications for how our professional development and learning is perceived, enacted, and valued.

Call to action

Given that ‘the fault lines are always in danger of becoming visible when language is looked at critically’ (Gray et al., 2018, p. 474), I do believe it is time to disturb the rhetorical structure of language that has found a cosy home in the discourse of educational reform and continuing teacher education. More profoundly, we need to challenge the slavishness to neoliberal ideas and economic persuasion that is helping it to thrive when its very connotations are antithetical to what we value about meaningful reform and the complexities of teacher growth.

There is no room for transactional language in the transformational space we occupy as educators .

There is an alternative and we as a profession have an option to critically deconstruct these blindly accepted terms towards welcoming a glossary that respects our highly skilled work and honours the deeply sophisticated nature of how we develop and learn .

Key messages

- A certain body of terminology synonymous with corporate doctrine has gained a foothold in the discourse of teacher continuing professional development .

- Largely rooted in a deference to the marketisation and consumerism of education, it features regularly in the discourse of education reform and associated teacher learning and development efforts

- An affront to teacher agency, the use of such language promotes a perception of teachers’ work and learning as technical, linear and unproblematic while fundamentally misrepresenting its complex nature particularly during times of reform.

- A universal blind acceptance of this business-like language register renders it largely unchallenged despite its incompatibility with all things educational.

- It is time to open the conversation about the legitimacy of such terms in the education context and explore more suitable alternatives

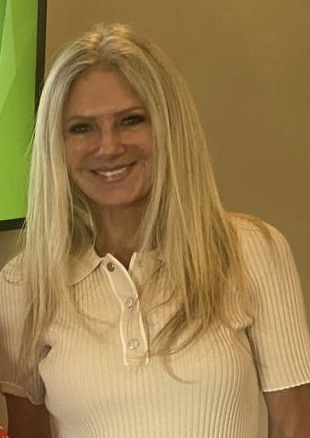

Dr. Ciara O' Donnell

Dr. Ciara O’Donnell has worked in the area of Continuing Professional Development for teachers for over 20 years. From 2013 to 2022 she was the National Director of the Professional Development Service for Teachers (PDST), Ireland’s first multi- disciplinary and cross-sectoral national CPD support service for teachers and school leaders.

Commencing her career as a primary school teacher, she has held a number of leadership positions in Irish teacher education in the areas of school leadership, educational disadvantage, curriculum development , CPD policy, design and research. Ciara now works as an independent education consultant and speaker specialising in teacher education, curriculum and school leadership while also working as a tutor with Maynooth University. Her published research explores the experiences and learning of teachers seconded to continuing teacher education and its impact on their future careers.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

References and further reading

Collini, S. (2017). Speaking of universities. London: Verso.

Del Percio, A. & Flubacher, M. ( 2017) Language, Education and Neoliberalism. In M. Flubacher, M. & A. Percio ( Eds) Language, Education and Neoliberalism. Bristol: Multilingual Matters

Department of Education and Youth (2025) Senior Cycle Redevelopment Implementation Support Measures. Dublin: The Department of Education and Youth. https://www.gov.ie/en/department-of-education/publications/senior-cycle-redevelopment-implementation-support-measures/

Gibbons, M., Limoges, C., Nowotny, H., Schwartzman, S., Scott, P. & Trow, M. (1994) The new production of knowledge. London: Sage Publications. https://ia801409.us.archive.org/30/items/mode1_2/mode1_2.pdf

Gray, J. O’Regan, P. & Wallace, C . (2018) Education and the discourse of global neoliberalism, Language and Intercultural Communication, 18:5, 471-477. https://doi.org/10.1080/14708477.2018.1501842

Hood, C. (1995) Contemporary Public Management: a new global paradigm? Public Policy and Administration, 10, 104-117.https://doi.org/10.1177/095207679501000208

Hargreaves, A. (1994) Changing Teachers, Changing Times: Teachers’ Work and Culture in the Postmodern Age. London: Cassell . https://www.scirp.org/reference/referencespapers?referenceid=1385110

Priestley, M., Biesta, G.J.J. & Robinson, S. (2015) Teacher Agency: An Ecological Approach. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Sahlberg, P. (2012). How GERM is infecting schools around the world? Retrieved from https://pasisahlberg.com/text-test/

Synder, T. (2017) On Tyranny: Twenty Lessons from the Twentieth Century : New York , Crown Publishing.

Timperley, H., Wilson, A., Barrar, H., & Fung, I. (2007) Teacher professional learning and development: Best Evidence Synthesis Iteration. Wellington: Ministry of Education.https://bibliotecadigital.mineduc.cl/bitstream/handle/20.500.12365/17384/154%20Teacher%20professional%20learning%20and%20development.%20best%20evidence%20synthesis%20iteration.pdf?sequence=1