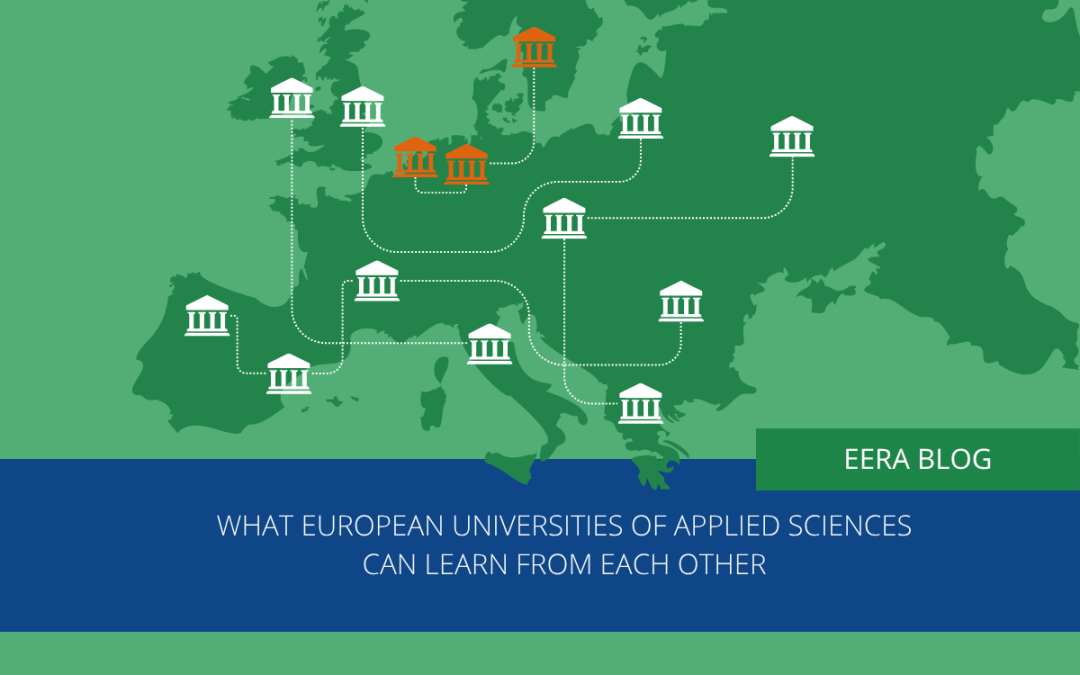

What European universities of applied science can learn from each other

New requirements for studying, teaching, and lifelong learning at European universities of applied sciences – An invitation to join the discussion

In Germany, challenges such as shrinking student numbers, shifting demands in the labour market, and the growing importance of lifelong learning are reshaping the role of academic organisations – including traditional (research) universities (Universität), universities of applied sciences (Hochschule für Angewandte Wissenschaften), colleges of education (Pädagogische Hochschule), and cooperative state universities (Duale Hochschule). These challenges affect universities of applied sciences (UAS) in particular, and this issue goes beyond Germany, extending to other European universities of applied sciences. But what exactly does that mean? Should we pay attention, and if so, why?

As European universities of applied sciences have to adapt, the Centre for Teaching and Learning at Bremen City University of Applied Science is investigating new paths for their strategic positioning.

What are universities of applied sciences (UAS)?

The difference between the two types of higher education institutions, (research) university and UAS in Germany, may not seem logical, but has developed over time. Universities have a long tradition of scientific-theoretical orientation and basic research. UAS have their origins in engineering colleges, academies, and colleges for design, social work, or business. In other words, they emerged from educational institutions with an applied focus. Consequently, they have always been practice-oriented, conducting applied science and focusing in particular on preparing their students for a profession.

In addition, although UAS, like universities, can acquire third-party funding for research projects, they lack the human resources to carry out this research. This restriction is also due to their practical orientation, since teaching loads at UAS are much higher than at universities. As German UAS are increasingly given the right to award doctorates, the separation between the two institutions is gradually disappearing. It can be assumed that this will lead to a shift in UAS from being primarily teaching-focused to becoming more research-focused institutions.

The clock is ticking: Challenges of UAS in Europe

Germany – Competition from private UAS

UAS in Germany are caught between a rock and a hard place. They are not full universities, so their opportunities to acquire third-party funding and conduct research are limited but they face fierce competition from private UAS, which are experiencing a rapid increase in student numbers. Although the currently prevailing right to award doctorates in many German federal states brings us closer to solving the first problem, the competition with higher education institutions in the private sector remains (Autor:innengruppe, Bildungsberichterstattung, 2022, p.195).

Sweden – Demographic pressure

Sweden is also affected by a decline in student numbers. This is the result of demographic change and primarily affects smaller UAS, such as Trollhättan (Universitetskanslersämbetet, 2023, p.50). The challenge, and at the same time the goal, is to strengthen internationalisation without compromising the quality of teaching.

Netherlands– Diversity-sensitive teaching as a challenge

While demographic change has played a major role in the first two cases, the difficulty of the Netherlands UAS lies in heterogeneous student populations and a high level of diversity among learners. This requires target group-oriented teaching, which in turn demands additional resources (OECD, 2024, p.5).

The international SLW@HAW project aims to address these and other challenges and to identify the strategies of the affected UAS.

Introducing the research project SLW@HAW

The project “Strategic Positioning of Universities of Applied Sciences in the Context of Studying, Teaching and Lifelong Learning” – or SLW@HAW – investigates how UAS across three European countries are positioning themselves in the key areas mentioned above. Our research team will examine governance approaches and institutional strategies in response to demographic, social, and geopolitical change.

In order to achieve this, we chose a mixed-method approach. At the beginning of the project, a document analysis of strategic university papers (e.g., policy papers) of the respective countries will be carried out to identify key topics. In addition, expert interviews will be conducted with selected university leaders. Subsequently, we intend to perform a quantitative survey of the activities and developments within lifelong education at UAS. To validate the results, a focus group will be organised with those already involved. It allows us to gain a comprehensive understanding of the strategies employed by UAS.

Our goal is to identify innovative strategies that help UAS remain relevant and resilient. On the micro level, education leaders, researchers, and policymakers can stay informed on promising strategies while contributing to a dialogue and shaping the future of higher education and higher education research. On the meso level, European universities can connect and learn from each other.[1]

The SLW@HAW research project runs from December 2024 to November 2027. It has been funded by the Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF, Germany) and is being carried out by an international research team at Hochschule Bremen City University of Applied Sciences (HSB).

Bremen University of Applied Sciences (Germany) enrolls nearly 9,000 students in 72-degree programs across engineering, natural sciences, economics, and social sciences. About 60% of these programs have an international focus, reflected in partnerships with 360 universities in 70 countries. International students make up 20% of the student body, representing around 110 nations. One of HSB’s greatest strengths is connecting the local with the global: it combines international orientation, strong practical relevance, a commitment to lifelong learning, and deep regional roots. In particular it can be seen through dual study programs and close collaboration with local industry, which drive innovation and workforce development in Bremen.The cooperation with UAS in Netherlands and Sweden provides valuable international perspectives that enrich the project.

Hanze University of Applied Sciences (Netherlands) is one of the oldest and largest UAS in the Netherlands, with over 28,000 students, including 2,500 international ones.

University West (Sweden) is a young UAS – founded in 1990 – located in Trollhättan, Sweden, with around 15,000 students. It offers practice-oriented programmes in close cooperation with the world of work.

The first results of the SLW@HAW research project are expected to be available by the end of 2025 or the beginning of 2026. We invite you to stay tuned and join in the discussion.

The SLW@HAW research team

Professor Dr. Annika Maschwitz

The project is led by Professor Dr. Annika Maschwitz. She is Professor for Lifelong Learning at Hochschule Bremen City University of Applied Sciences, School of International Business. She is also Academic Director of the Centre for Teaching and Learning and Vice President of Academic Affairs and Internationalisation

Dr. Johanna Bruns

Andrea Boerens M.A.

Andrea Boerens M.A. is currently completing her doctoral studies. She studied Social Sciences, Sociology, and Social Research. Her research focuses on programme development, higher education, and lifelong learning, with a special emphasis on the opening of higher education institutions. Since July 2023, she has worked at Bremen University of Applied Sciences in the Curriculum Lab. As a research associate in the SLW@HAW project, she conducts expert interviews and qualitative analyses.

Jessica Langolf M.A. (Blog author)

With a background in Educational Science, Philosophy, and Empirical Educational Research, Jessica Langolf M.A. is an early career researcher at the Centre for Teaching and Learning at Hochschule City Bremen University of Applied Sciences, focusing on higher education and organisational research. She has accumulated experience in diverse academic fields, including the writing center, qualitative research on organisational culture as part of the Excellence Cluster “Internet of Production,” science communication at the Center of Excellence Women and Science (CEWS), and worked in the Research and Transfer Department focused on (academic) female entrepreneurship.

Greta Kottwitz M.A.

Greta Kottwitz M.A. completed her Bachelor’s degree in Cultural and Gender Studies and went on to deepen her focus on sociological questions during her Master’s studies at the University of Oldenburg. She has gained experience in a variety of academic contexts, including transfer management, human-computer interaction, as well as continuing education and education management. She is currently pursuing a PhD at Bremen University of Applied Sciences, where she is researching lifelong learning in Universities of Applied Sciences.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

[1] Similar to another project at Bremen University of Applied Sciences: STARS EU.

Autor:innengruppe Bildungsberichterstattung. (2022). Bildung in Deutschland 2022: Ein indikatorengestützter Bericht mit einer Analyse zum Bildungspersonal. wbv Publikation.

OECD. (2024). Education at a glance 2024: Country note – Netherlands. OECD Publishing. Retrieved May 15, 2025, from https://www.oecd.org/en/publications/education-at-a-glance-2024-country-notesfab77ef0-en/netherlandsf17c5d6a-en.html

Universitetskanslersämbetet. (2023). An Overview of Swedish Higher Education and Research 2023. Retrieved May 15, 2025 from https://www.uka.se/download/18.2215701c18c6242f0141e50f/1702630438362/UK%C3%84_An%20overview-engelska%20%C3%A5rsrapporten_webb_enkelsidor.pdf