What PhD Dissertations Reveal About Early Childhood Education in Spain

In educational research, peer-reviewed journal articles often take centre stage. Yet another rich source of knowledge is frequently overlooked: doctoral theses. These in-depth works capture new, exploratory directions and provide a unique window into how research evolves in specific national contexts.

This study analysed 84 doctoral dissertations in Early Childhood Education (ECE) defended in Spain between 2020 and 2024, retrieved from the Spanish repositories TESEO and Tesis en Red. Using a descriptive–retrospective methodology supported by bibliometric analysis, it mapped emerging research priorities, identified the universities most active in ECE scholarship, and examined how this output aligns with current educational policies, including the LOE–LOMLOE reforms on competency-based learning, inclusivity, and cross-curricular values.

Why look at doctoral theses?

PhD dissertations represent the culmination of years of academic inquiry and often capture new, exploratory directions that may not yet appear in mainstream literature. As Fuentes and Arguimbau (2010) note, a dissertation contributes original and specialized knowledge, offering valuable context to assess what matters most in a given field. This is especially true in Early Childhood Education, a stage recognized for its importance in long-term child development.

A research gap and a unique methodology

Despite their potential, doctoral theses have historically been classified as “grey literature,” meaning they are not always easily accessible. However, thanks to open repositories such as TESEO and Tesis en Red in Spain, it is now possible to conduct large-scale bibliometric and content analyses.

This study began by identifying 96 theses defended between 2020 and 2024. After applying inclusion criteria focused on Early Childhood Education—such as relevance of the topic, educational stage addressed, and methodological transparency—84 dissertations were selected for analysis.

Data extraction followed a structured protocol including:

- Thesis title and year of defence

- University and department

- Author and supervisor gender

- Main research theme (coded into thematic categories)

- Methodological approach and sample characteristics

Thematic classification was conducted using both manual coding and keyword mapping, ensuring reliability through inter-coder agreement checks. Quantitative data were analysed descriptively to identify trends, while qualitative insights from abstracts and introductions provided context to interpret the statistical patterns.

We focused on variables such as thesis topics, authorship gender, supervising institutions, and frequency of certain methodological approaches.

The goal was not only to quantify scientific output, but also to understand how it aligns with current educational needs and policies, including the recent reforms in Spain such as LOE-LOMLOE — a legal framework updated in 2020 that emphasizes competency-based learning, inclusivity, and the integration of cross-curricular values like sustainability, gender equality, and digital literacy.

Key findings: What the data shows

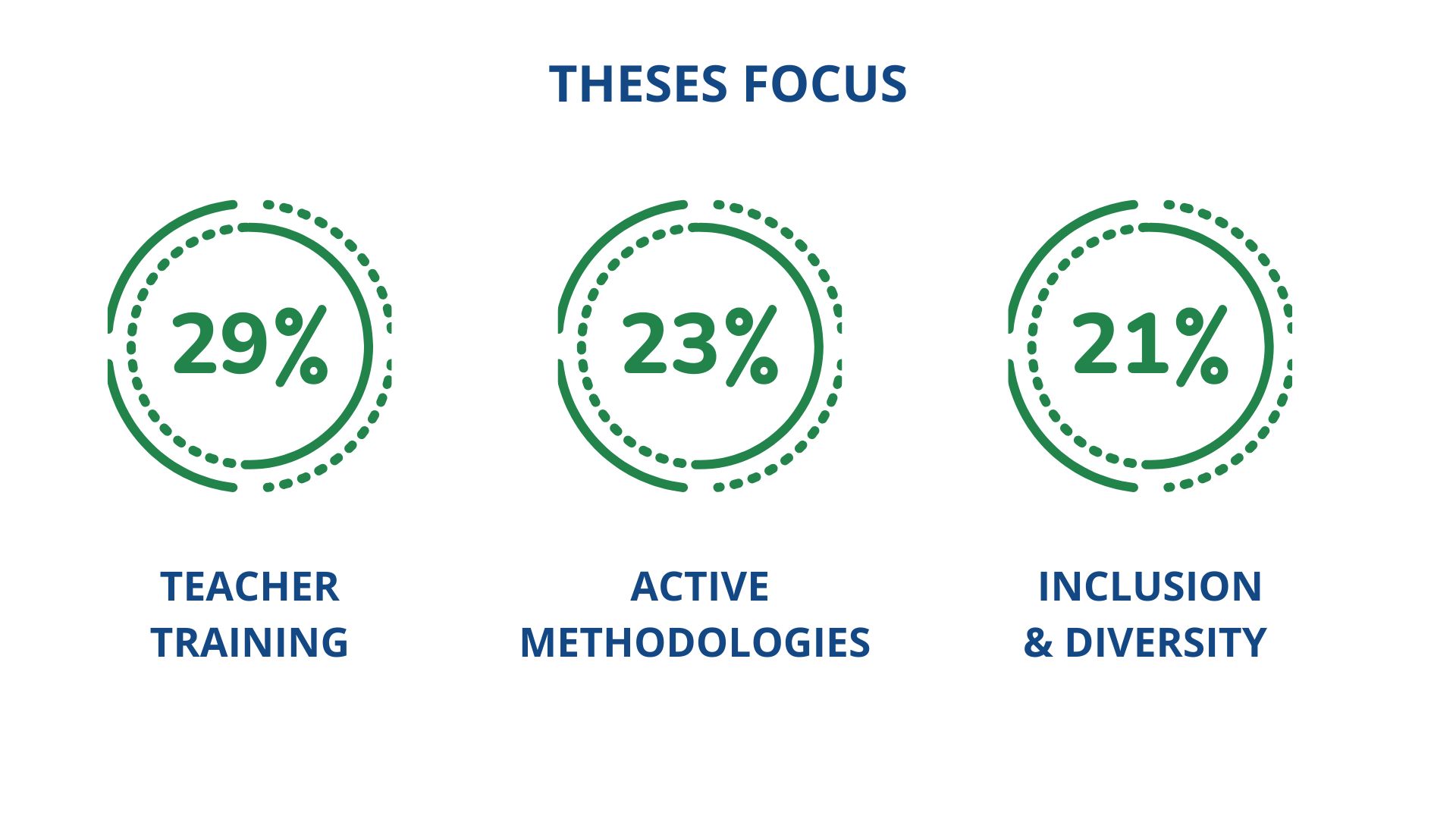

The analysis revealed clear thematic patterns. Teacher training was the most prevalent focus, appearing in nearly 29% of the theses, followed closely by research on active methodologies at 22.6%. Inclusion and diversity were central in 21.4% of dissertations, highlighting the field’s attention to equity in early learning environments. Other areas such as socio-emotional development, digital competence, and neuropsychology were represented to a lesser extent but still contributed to a diverse research landscape.

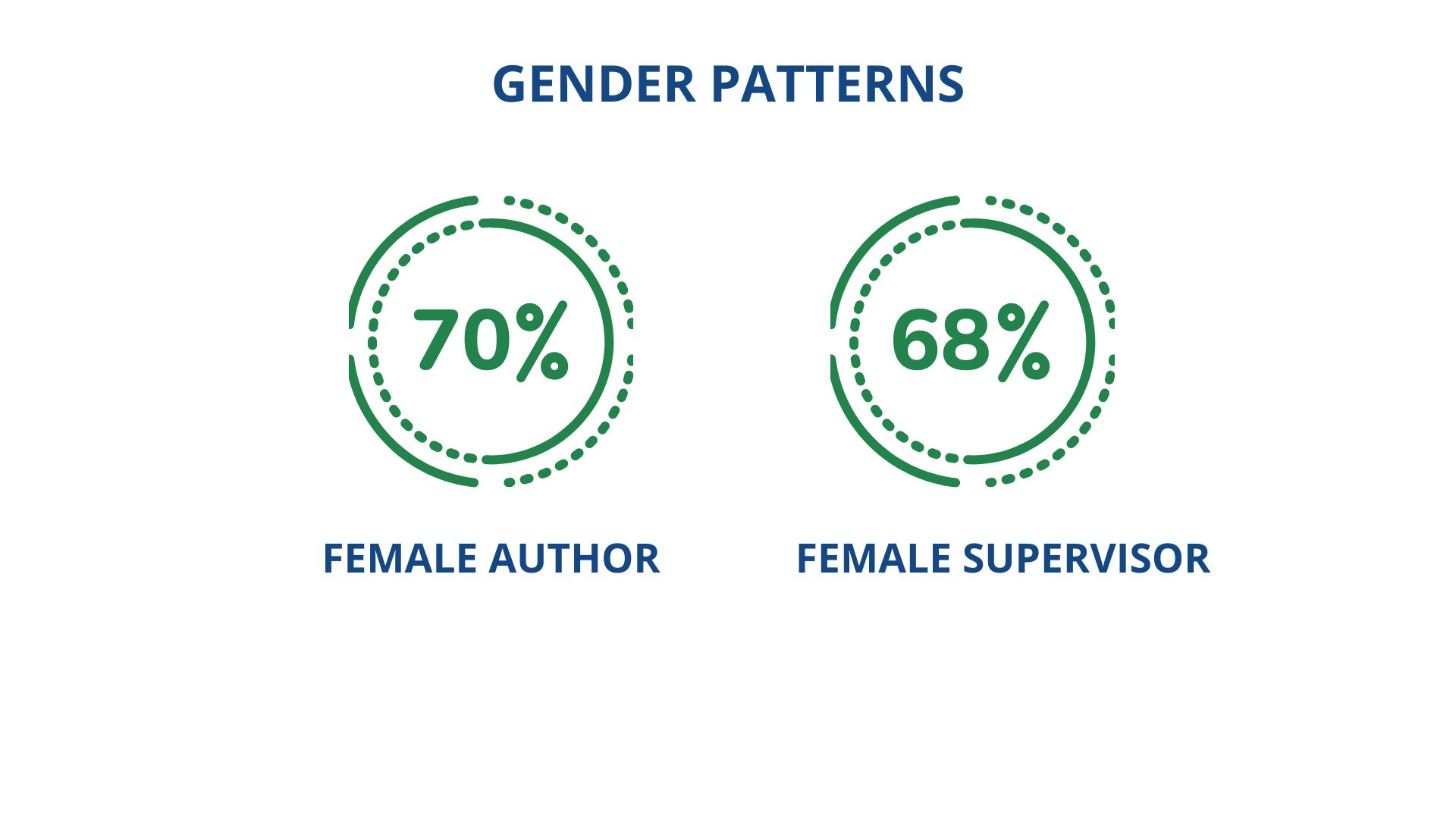

Gender patterns were also striking. Women authored over 70% of the dissertations and supervised 68% of them, reflecting a strong female presence in ECE research. The data further suggested gendered differences in research focus: female authors more frequently explored inclusion, diversity, and emotional development, whereas male authors were somewhat more represented in technology-related studies.

Institutional analysis showed that doctoral production was concentrated in a few universities, which acted as hubs for innovation and scholarly collaboration. Departments specializing in Didactics and Scholar Organisation, and Developmental and Educational Psychology stood out for their volume of research, indicating the presence of focused academic communities with shared research priorities.

The findings point to a vibrant yet uneven research ecosystem in Spain’s Early Childhood Education doctoral output. While dominant themes like teacher training and inclusion align with both national and international priorities, there are emerging areas—such as digital competence in early years and socio-emotional skill development—that remain underrepresented despite their growing relevance in 21st-century classrooms.

The gender patterns observed are not only statistically significant but also sociologically meaningful. The strong female representation among both authors and supervisors may influence the thematic focus of the research, possibly reinforcing inclusive and affective dimensions in ECE scholarship.

The concentration of doctoral production in a handful of universities—particularly in Murcia, Valencia, Castilla-La Mancha, and Salamanca—indicates that these institutions have become influential research hubs, often developing ‘scientific schools’ focused on specific ECE themes. Interestingly, these are not Spain’s largest universities, yet they play a central role in shaping national ECE research agendas. While this concentration creates opportunities for strong collaborative networks, it also raises questions about whether the diversity of perspectives and equitable access to doctoral research opportunities are being fully ensured across the country.

Why this matters for policy and practice

Understanding the trends in doctoral research offers policymakers a unique, evidence-based perspective on where Early Childhood Education (ECE) is heading and what areas may require strategic support.

For example, the prominence of teacher training in nearly 30% of theses signals a continued need for professional development programs that equip educators with the skills to implement active and inclusive methodologies effectively. Similarly, the strong focus on diversity and inclusion suggests that policy measures should prioritize resources for supporting children with diverse learning needs, as well as monitoring the impact of these policies in the classroom.

Beyond guiding policy priorities, the findings also highlight gaps where intervention may be required. Certain research areas, such as digital literacy in early years or socio-emotional development, remain underexplored relative to their growing importance in 21st-century education.

Identifying these gaps allows education authorities to design targeted funding programs, encourage collaborative research initiatives, and foster innovative pedagogical practices. Additionally, recognizing which universities act as research hubs can inform decisions about where to concentrate partnerships, training initiatives, and dissemination of best practices, ultimately strengthening the national ECE system.

A call to recognize hidden knowledge

Doctoral theses contain rich insights that are often invisible to mainstream education stakeholders, yet they can significantly influence practice and policy. By treating these works as valuable sources of evidence, institutions and policymakers can expand their understanding of emerging trends and innovative methodologies in ECE. For instance, the clear gender patterns observed among authors and supervisors highlight not only the strengths of female representation in the field but also the need to examine how these dynamics may influence research focus and professional development.

Moreover, integrating knowledge from doctoral theses can enhance collaboration between research and practice. Educators can draw inspiration from experimental or pilot approaches documented in dissertations, while universities and research centres can use these findings to foster cross-institutional networks. Encouraging access to and discussion of grey literature promotes a more inclusive academic ecosystem, where evidence from diverse sources informs educational reform. Ultimately, acknowledging and leveraging the insights hidden in doctoral work is a step toward a more reflective, innovative, and effective Early Childhood Education system in Spain.

Overall, doctoral theses should be recognised as more than academic milestones; they are strategic sources of evidence for shaping educational policy, informing teacher training curricula, and identifying innovation opportunities in early years pedagogy.

Key Messages

— Doctoral theses offer deep insights into emerging research trends in Early Childhood Education (ECE) in Spain.

— Between 2020 and 2024, key themes included teacher training, active methodologies, and diversity/inclusion.

— Women represented the majority of thesis authors and supervisors, showing significant gender patterns.

— Academic production is concentrated in specific universities, pointing to strong institutional research hubs.

— The findings help identify current educational challenges and guide future improvements in ECE policy and practice.

Paula Martínez-Enríquez

International Doctoral School of UNED (Spain)

Paula Martínez-Enríquez is a PhD candidate in Education at the International Doctoral School of UNED (Spain). Her research focuses on quality assurance in education and emerging trends in Early Childhood Education, as well as Project-based methodology in Early Childhood Education and democratic pedagogies. She is currently funded by the Regional Government of Madrid through the 2023 predoctoral research training program.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Eliasson, S., Peterson, L. & Lantz-Andersson, A. A systematic literature review of empirical research on technology education in early childhood education. Int J Technol Des Educ 33, 793–818 (2023). https://doi.org/10.1007/s10798-022-09764-z

Yu, S., & Cho, E. (2022). Preservice teachers’ attitudes toward inclusion. Early Childhood Education Journal, 50(4).https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10643-021-01187-0

Fuentes, M., & Arguimbau, M. (2010). Tesis doctorales y conocimiento pedagógico. Editorial UOC.

Repiso, R., Torres-Salinas, D., & Delgado, E. (2011). Scientific grey literature and doctoral dissertations. ICONO 14, 11(2).

López-Gómez, E. (2016). Analysis of doctoral theses in educational tutoring. Revista General de Información y Documentación, 26(1).http://dx.doi.org/10.5209/rev_RGID.2016.v26.n1.53047