Fostering Creativity in the Classroom – developing a cross-curricular module in ITE

Outside of the core curricular content that makes up initial teacher education (ITE) programmes, there are increasing callsfor input on a variety of pedagogical, social, cultural, and competence-based issues that impact future teaching practice (MacPhail et al., 2022). Most higher education institutions possess expertise in a range of innovative areas, but the practicalities of timetables, student availability, and academic structures often mean students must choose one or two five-credit, level nine modules from a range of electives. This blog outlines an effort to combat this through an integrated module on the Professional Masters in Education PME (Post-Primary) at Dublin City University, Ireland, which combines Digital Competencies, English as an Additional Language, and Drama-based learning under the umbrella of ‘Fostering Creativity in the Classroom’.

Fostering creativity in the classroom – developing the module

We know that cross-curricular and integrated teaching can facilitate students in making creative connections and solving complex problems (Harris & de Bruin, 2017). Motivated by this, we began examining our content, values and teaching approaches and quickly realised a common thread of creativity ran through our work. Our module, ‘Fostering Creativity in the Classroom’ places explicit focus on the role of the teacher in fostering creativity and innovation in the post-primary classroom. Using a multidisciplinary approach, we allowed students to explore and experience a range of creative, collaborative and playful approaches to fostering creativity in teaching and learning. This was achieved through lectures, workshops, and a range of strategies from the Digital Learning(e.g. digital storytelling), Drama (e.g. soundscapes), and Linguistic Responsiveness (e.g. multilingualism) domains.

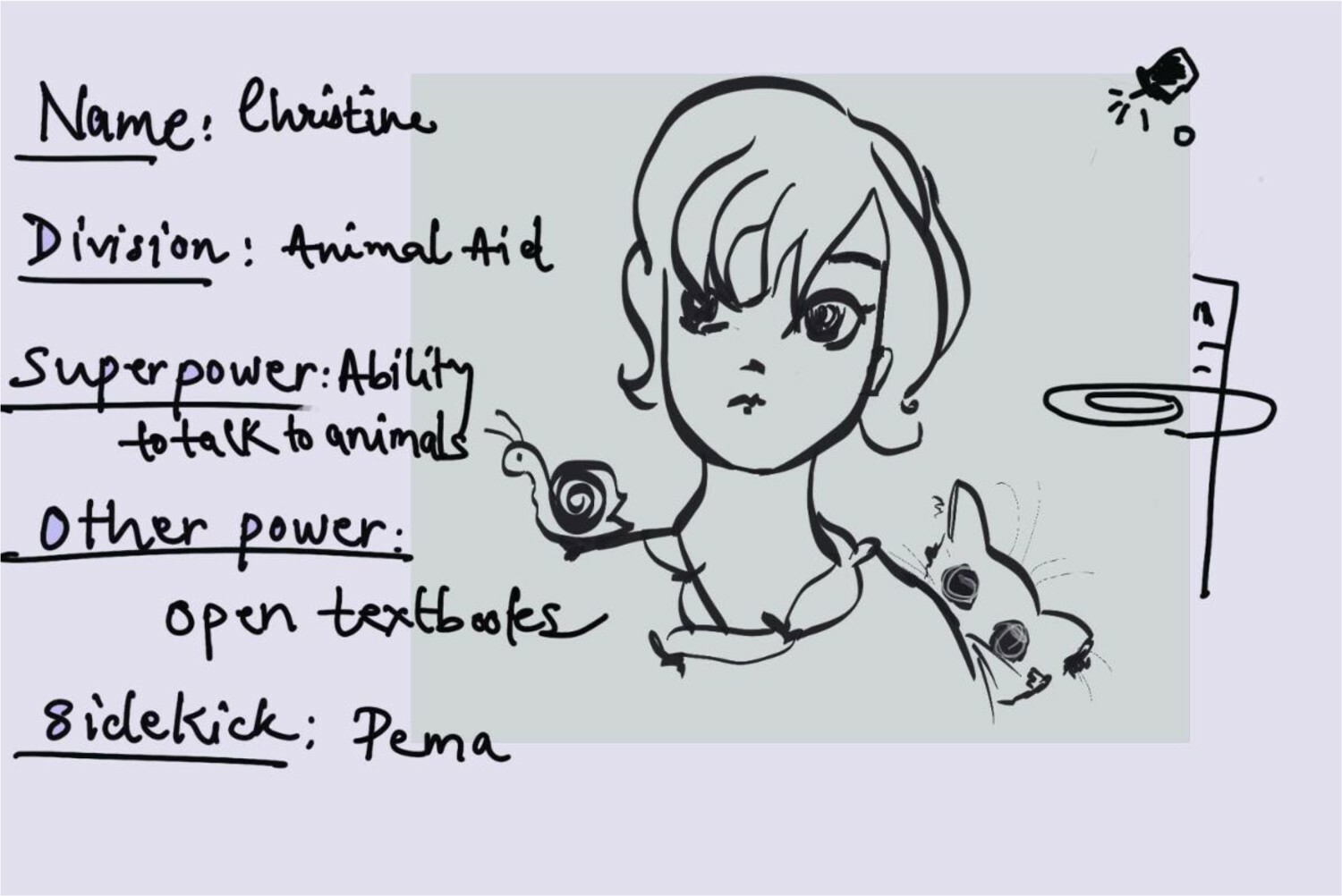

Underpinned by theories of creativity in education (e.g. Gilhooly & Gilhooly, 2021), our students, who are pre-service teachers, worked together to experiment with creative approaches, reflect on their experiences, and plan their practical implementation in the future. In order to draw the different strands together under the theme of creativity, we designed an innovative assignment. The assignments tasked students (in small groups) with creating a digital story on the theme of ‘fostering creativity and innovation in the post-primary classroom’. Their target audience was future PME students and practising teachers. Videos considered how digital media, drama and linguistically responsive strategies can enhance practice and encourage pupil creativity. Groups reflected on the strategies explored during the module and considered their application across curricular subjects. Videos were to be presented as a cohesive narrative or story and include a variety of audio-visual content.

Our reflections

Reflecting on the process, we were pleased it did not result in merely fitting our ‘pieces’ together, but in creating something unique that was enriched by our individual curricular areas. As academic staff, collaborating on the design and delivery provided us with opportunities to learn from each other’s curriculum design and facilitation approaches while demonstrating to students the connections that exist between subject areas. Our challenges were primarily around articulating our vision and structuring the delivery. While, as academic staff, our initial vision for the module was clear, our individual ‘flavours’ of that vision came through at first. It wasn’t until the second iteration of the module that we began to speak in one voice. The structure of the module delivery was another aspect that we found challenging initially and that we improved over time. In the first iteration of the module, we split the content into ‘blocks’, where each team member delivered their content in sequence after one another. We found that this meant students saw the module as three separate parts, and while that made sense in terms of the coherence of each aspect, it took away from the overall flow and interconnected nature of the work we were trying to achieve. Rectifying this was more than the simple act of moving lectures from one week to another. Instead, it necessitated the alteration of certain aspects of content so they more naturally connected to the other areas of study. We also spent more time ‘in’ each other’s lectures in order to display a unified voice.

Students’ impressions

Feedback from students on the experience of participating in this integrated module contained positives and potential areas for improvement. Students commented on the module’s ambitious and forward-thinking nature, saying it was ‘pretty ambitious’ and ‘very relevant in modern education’. They noted that they learned a lot from each strand and, perhaps most importantly, they learned more from how the strands linked together. Comments included: ‘Lovely to have different strands (E.g., Digital Media, Drama-based learning) each week. Helped the creativity’ and ‘It helps shift your focus from the ways in which you were taught at school and to focus on all of the possibilities that exist for enhancing your lessons and making them more meaningful’.

On the other hand, students also found areas challenging. For example, they found that the three strands meant there was a lot to take in. Comments included ‘There was a lot of information in each module[strand] and not enough time to get to grips with all of it’. Some also found it difficult to see how everything aligned under the umbrella of developing pupils’ creativity in the classroom. Comments included ‘personally felt that there was a bit of a disconnect between the three strands’ and that they ‘did not find the necessarily all aligned under the umbrella of creativity’.

Fin

Our efforts to combine three elective strands into one coherent module were not without their challenges. However, as lecturers, we found that the process not only allowed us to examine connections across curricular areas but facilitated the development of a more nuanced version of ‘creativity’ than we had delivered before. Students also recognised the value of our integrated approach, which is encouraging. However, their comments also provide scope for improvements in the future. For example, further work may be needed to increase the connection between strands so that students see the module as a cohesive approach to develop pupils’ creativity in the classroom.

Key Messages

- The practicalities of ITE programmes often make the provision of additional pedagogical, social, cultural, and competence-based initiatives challenging

- We document the development of a cross-curricular, integrated module “Fostering Creativity in the Classroom”

- The module integrates Digital Learning, Drama-based Learning, and Linguistic Responsiveness

- The process provided us, as academic staff, with the opportunity to enrich our individual curricular areas and practice by learning from each other’s design and facilitation approaches.

- Students found the module to be ambitious and forward-thinking, and learned more from how the curricular areas fitted together to ‘foster creativity in the classroom’.

Dr Peter Tiernan

Associate Professor in Digital Learning and Research Convenor for the School of STEM Education, Innovation and Global Studies in the Institute of Education at Dublin City University.

Peter is an Associate Professor in Digital Learning and Research Convenor for the School of STEM Education, Innovation and Global Studies in the Institute of Education at Dublin City University. He lectures in the areas of digital learning, digital literacy and entrepreneurship education. His current research focuses on digital literacy at post-primary and further education level as well as entrepreneurship education for third level lecturers and pre-service teachers.

Peter was shortlisted for the DCU President’s Award for Excellence in Teaching and Learning in 2021.

Dr Fiona Gallacher

Assistant professor in the School of Applied Language and Intercultural Studies (SALIS) at Dublin City University

Fiona Gallagher is an assistant professor in the School of Applied Language and Intercultural Studies (SALIS) at Dublin City University. Before this, she worked as a teacher and CELTA teacher educator in Sudan, Italy, Spain, Ireland, the US, Australia and Portugal. Her research interests lie primarily in the fields of second language acquisition, TESOL and bi/multilingual education with particular reference to: L1 use in language learning and teaching; translanguaging and plurilingual pedagogies; and teaching and learning in the linguistically and culturally diverse primary and secondary school classroom.

She has published widely in her field, both as the author/co-author of various EFL textbooks and teacher guides and in high-ranking peer reviewed journals and edited volumes.

Dr Irene White

Assistant professor in English and Drama Education in the School of Human Development at the Institute of Education, Dublin City University.

Dr Irene White is an Assistant Professor in English and Drama Education in the School of Human Development at the Institute of Education, Dublin City University. She is the Programme Chair of the Professional Master of Education and teaches across a range of initial teacher education programmes. Irene taught English and Drama at the post-primary level for twelve years, during which time she was a mentor for initial teacher education students and a State Exams Commission examiner for the Leaving Certificate Applied Programme.

Irene’s research straddles the arts and education sectors, with a particular focus on creative mindsets, creative learning environments and creative activity for health and wellbeing. Her PhD examined creativity in participatory arts initiatives and articulated a Participatory Arts for Creativity in Education (PACE) model, an applied participatory arts model aimed at fostering creativity in education.

Irene is Chair of the Board of Directors for Upstate Theatre Project, a community-engaged participatory arts organisation funded by the Arts Council of Ireland. Her work in the field of participatory arts includes her role as artist and director with Upstate Theatre Project on The Crossover Project, a cross-border, cross-community participative drama programme, and her work with students from the Steinhardt School of Culture, Education and Human Development, New York University on the study abroad programme. Irene has also worked with Smashing Times Theatre and Film Company on the ‘Acting for the Future’ programme using drama and theatre performance to promote positive mental health and the ‘Acting for Change’ programme using drama to explore cultural diversity and identity and promote anti-racism, anti-sectarianism and equality.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Gilhooly, K. J., & Gilhooly, M. L. M. (2021). Aging and creativity. Academic Press.

Harris, A., & de Bruin, L. (2017). Steam education: Fostering creativity in and beyond secondary schools. Australian Art Education, 38(1), 54–75.

MacPhail, A., Seleznyov, S., O’Donnell, C., & Czerniawski, G. (2022). Supporting the Continuum of Teacher Education Through Policy and Practice: The Inter-Relationships Between Initial, Induction, and Continuing Professional Development. In Reconstructing the Work of Teacher Educators: Finding Spaces in Policy Through Agentic Approaches—Insights from a Research Collective (pp. 135–154). Nature.