Transformative learning in educational sustainability as collective resilience and resistance

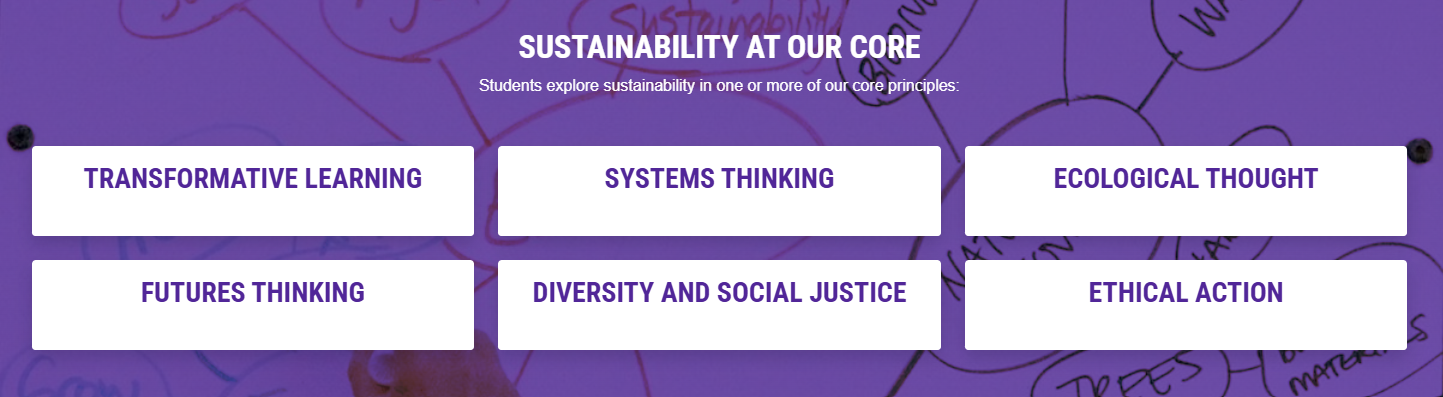

Over the last two years, I have been conducting research on how doctoral students experience transformative learning in an educational sustainability program. We define transformative learning as a process that engages the head, heart, and hands in critical reflection, values introspection, social engagement, and empowerment towards sustainability (Grund et al., 2024; Papastamatis and Panitsides, 2014; Sipos et al., 2008). The transformative learning journey is not a straight line, rather it is dynamic, fluid, adaptive, and recursive in nature, allowing each learner to experience it differently (Boström et al., 2018; Grund et al., 2024; Rodríguez Aboytes and Barth, 2020). We argue that although a transformative moment can occur within an individual, transformative learning is a social and collaborative process.

I am the director of the educational sustainability program and an associate professor, teaching many courses within the program. I have loved learning from students on how, to what extent, and when they experience transformative learning, but the process is mutual. As much as the students have been transformed, so have I. Over the last year, the attacks on sustainability have changed these relationships and created a different type of transformative learning, one that feels like collective resistance. The emotional trauma of seeing these attacks has led to a deeper kinship, one that binds us together through this struggle and collective desire to build a safe space for all.

Sustainability education in a hostile political environment

I define sustainability as the morally courageous pursuit of a just, inclusive, and equitable future where humans and the environment can thrive. However, this pursuit can come with fatigue and advocating for change is not without struggle. As change agents, we take on those struggles in the hope of moving forward in a different way—one that reflects justice and equity. We learn from the past and challenge White Supremacy culture and systems of domination. We see the interdependence of environmental and human health and treat the environment as a stakeholder in our decision-making.

On the morning of November 5th, 2024, I woke to a Trump victory, which all but sealed the destruction of equity and inclusivity movements in U.S. higher education institutions. The topics that lay the foundation of sustainability education—social justice, ecological health, cultural inclusivity, and equitable access to resources—all lay on the chopping board. I felt like I couldn’t breathe, couldn’t move, the weight of what this means to me, to my students, barreled down on me. I was teaching a class entitled, “Social Justice for a Sustainable Society,” and my students were preparing case studies on reparative futures (Sriprakash et al., 2020); but how was I supposed to show up for this authentically, knowing the just futures they were imagining will be under attack for at least the next four years?

I did show up for my classes and for my students, but it was different. In some cases, I cried with my students, in others, I urged them to keep going, to not let this hostile political environment silence them and their achievements. I fiercely defended this program as a safe space for all, especially in this time of difficulty. My job changed, my relationship with my students changed. Working together through our pain and vulnerability, we found a collective strength and supported each other in a way that increased our resilience to do the work of sustainability.

Building strength through vulnerability

One of the features of our program that builds relationships, and collective learning is the one-week, in-person residency that is required every summer for three years. The educational sustainability doctoral program is online, except for this yearly residency. The residency is frequently mentioned by our students as one of the most transformative experiences in the program. This year (June 2025), I took a different approach to planning the residency. Rather than bringing computers and learning about sustainability competencies and research methods, we focused on the heart and hands parts of transformative learning (Sipos et al., 2008) and the social and emotional connections between each other (Papastamatis and Panitsides, 2014).

I planned activities for us that would require leaving our devices behind and connecting with nature and each other, like canyoning (repelling down waterfalls). The canyoning experience, in many ways, mirrored the transformative learning design of the program—it required collaboration, had moments of difficulty, struggle, and vulnerability, and concluded with a sense of collective strength, resilience, and empowerment.

The students similarly reflected on how canyoning was transformative and created a unique bond through vulnerability and trust. One student wrote about the canyoning experience:

Everyone that participated in that experience was truly vulnerable and also supportive of each other. We had to let our guards down to focus on completing the journey down the canyon and leaned on each other to do so. That required a significant amount of trust and literal handholding.

In the end, we were closer with our peers after the canyoning experience

Another student reflected on the emotional safety created through this experience:

One particularly memorable experience that fostered the community was the canyoneering trip, where we rappelled down an 80-foot waterfall.

Supporting each other through adrenaline (and fear) led us to encouragement and emotional safety.

Yet another student reflected on the emotional support and kinship that this experience fostered:

The fact that I faced my fear, endured the pain, and still came away feeling proud says a lot about the strength and healing I’ve cultivated.

The canyoning experience pushed many people’s physical and emotional limits, but together we were strong, resilient, and could tackle anything put in our path. The canyoning became an analogy for our relationships in this program and our pursuit of sustainability.

We may feel fear, face struggles, even trauma, but through vulnerability, trust, and support, together, we can persist.

This one experience is not the full story, but it does provide a glimpse into the shared experience of striving and struggling for sustainability in a time of difficulty and finding that together we are more resilient. It also opens the conversation for viewing transformative learning as a physical and emotional endeavor, rather than primarily cognitive.

I started 2025 full of fear and sadness. I came to my classes with that vulnerability—with tears and at a loss for any answers or solutions to the hardships we are facing. My students held my hand as much as I held theirs. The determination that I feel today to use everything I have to uplift their voices and ensure that they have this program as a space for healing, hope, and emotional safety is more steadfast than ever. I am transformed by the strength I see in our collective capacity.

Transformative learning as a form of collective resistance

Transformative learning is a recursive and co-generated process. Educators must be willing to be vulnerable, open, and receptive to growth and change. In this way, we are not experts disseminating knowledge; instead, we are learning alongside our students and growing because of them. Also, sometimes in advocating for sustainability, we need to take time away from writing, reading, and presenting to build our resilience as change agents with our community.

I feel more engaged and enraged to fight for a sustainable future today than I have ever felt in the past. Holding this space where we could be vulnerable, created emotional safety, and from that space of safety and support, I can continue to fight and advocate for a more just future.

ECER 2025 – Presentation

To learn more about the educational sustainability students and their perspectives on transformative learning, please attend our presentation at ECER:

“Multi-year study on Students’ Transformative Learning Journey through an Educational Sustainability Doctoral Program”

Session Number: 30 SES 02 B

Session Title: 30 SES 02 B: Education and Transformation

Session Location: University of Belgrade, room tbc

Session Time: 09/Sept/2025, 15:15 – 16:45

Dr. Erin Redman

University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, USA.

Erin Redman is the program director and associate professor of Educational Sustainability in the School of Education at University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point. Prof. Redman comes to UWSP from Leuphana University of Luneburg (Germany) where she has been a research associate and program lead on an international sustainability education collaboration for the Global Consortium of Sustainability Outcomes (GCSO). Prior to joining Leuphana, Prof. Redman created and led the Sustainability Teachers’ Academy, a professional development program for in-service teachers from all over the United States. She was also a faculty member at the National University of Mexico (UNAM), where she integrated sustainability throughout their undergraduate programs as well as designed a stand-alone sustainability undergraduate program. https://www.uwsp.edu/directory/profile/erin-redman/

08 - 09 September 2025 - Emerging Researchers' Conference

09 - 12 September 2025 - European Conference on Educational Research

Since the first ECER in 1992, the conference has grown into one of the largest annual educational research conferences in Europe. In 2025, the EERA family heads to Serbia for ECER and ERC.

In Belgrade, the conference theme is Charting the Way Forward: Education, Research, Potentials and Perspectives

Emerging Researchers' Conference - Belgrade 2025

The Emerging Researchers' Conference (ERC) precedes ECER and is organised by EERA's Emerging Researchers' Group. Emerging researchers are uniquely supported to discuss and debate topical and thought-provoking research projects in relation to the ECER themes, trends and current practices in educational research year after year. The high-quality academic presentations during the ERC are evidence of the significant participation and contributions of emerging researchers to the European educational research community.

By participating in the ERC, emerging researchers have the opportunity to engage with world class educational research and to learn the priorities and developments from notable regional and international researchers and academics. The ERC is purposefully organised to include special activities and workshops that provide emerging researchers varied opportunities for networking, creating global connections and knowledge exchange, sharing the latest groundbreaking insights on topics of their interest. Submissions to the ERC are handed in via the standard submission procedure.

Prepare yourself to be challenged, excited and inspired.