Reimagining Global Education together: towards a more comprehensive and contextually relevant understanding for the future

Global education is an emerging research theme in Finland. Although primarily framed within a European context, it is important to ensure that any form of global education is locally relevant. Within a local Finnish context, then, research done by different scholars at different institutions must be in tune with one another. With this purpose in mind, scholars from various universities in Finland met for a three-day retreat organised by the Global Education Research in Finland (GERIF-network) on 9 December 2021 at the Konnevesi research station, near the town of Jyväskylä.

Global education research, as any research topic, benefits from being mapped and made visible. This allows peers to provide feedback, while providing room to explore and consider new ideas for further research. It is particularly worthwhile for global education to be subject to a collaborative process of inquiry because of the challenges the topic holds, both ideologically as well as in more practical educational terms.

First, globalisation has proven to be an elusive concept to grasp. Some consider globalisation to be an “ideological construction”, while others see globalisation as a historical process of structural change at the social, economic, political, and cultural level. From a national perspective, the way in which countries interpret globalisation determines how global education will be implemented. Because these interpretations can be greatly nuanced, global education can sometimes also be understood as international education.

Second, these implementations of global education are generally underpinned by a guiding ideological framework. This ideological foundation defines the purpose of global education according to its view and envisions what the ideal ‘global citizen’ would look like. Among the definition outlined in the Maastricht Global Education Declaration, there are those proposed by the OECD and UNESCO in addition to more critically oriented conceptions such as those by the Gesturing Towards Decolonial Futures research community and scholars like Vanessa Andreotti.

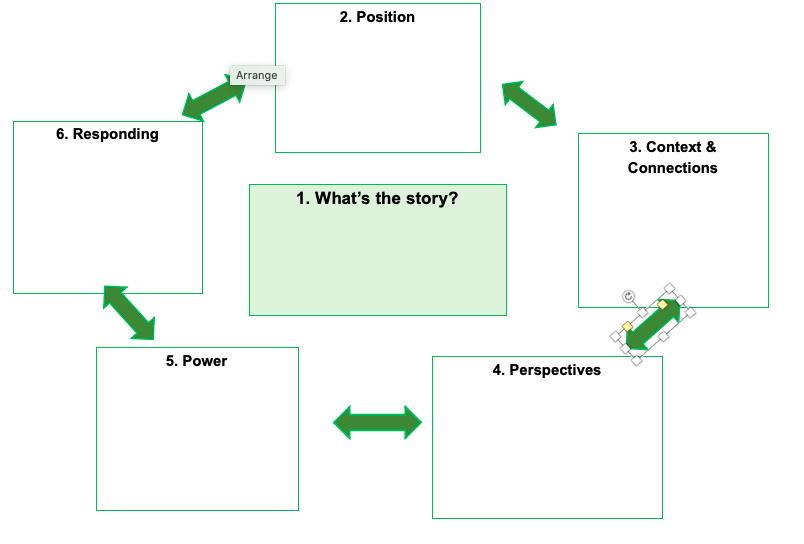

Because global education involves the elusive ‘global’ component, the need to include diverse viewpoints is essential. This is why the five workshops of the retreat were participant-led and emphasised constructive dialogue. The underlying idea of engaging in dialogue is to progress towards a common understanding of the object of discussion with the willingness to diverge from one’s original viewpoints. A commitment to hear and acknowledge other perspectives is what is needed when trying to come to a common understanding of global education and to teach it in schools. Reaching a common understanding is not necessarily synonymous with reaching consensus. Rather, it is about providing equal ownership of the process of creating meaning.

Providing room for the participants to recognise their own contribution to the debate is precisely how the five workshops proceeded. The first workshop invited the participants to critically consider established definitions of global education and to reflect upon one’s own understandings. Touching upon a similar theme, the second workshop probed at the limits of global education. The aim was not to set limits, or to define what global education should and should not be about, but to understand issues, one’s own perspective, and others’ perceptions. Listening to yourself and others fosters an awareness of what people think and why they think the way they do while also avoiding polarisation.

In a similar spirit, the third and fourth workshops explored how people, or in educational contexts, learners can co-create knowledge in collaborative learning spaces. Both workshops emphasised the value of diverse perspectives in coming to a common understanding. While the third workshop put forth the idea that the process of accommodating new knowledge coincides with a “groan phase”, a moment of tension as the mind is trying to transcend its understanding, the fourth workshop focussed on intercultural dialogue.

Lastly, the fifth and final workshop revolved around the purpose of critical thinking which by now may have become somewhat of a buzzword. In relation to dialogue and collaborative knowledge creation, critical thinking has the disadvantage that it occurs primarily within the individual mind. As an alternative, organic thinking proposes a shift from anthropocentrism to a more connected form of thinking that involves others and the environment as a whole. As such, thinking becomes a collective activity that converges to a common understanding.

In summary, the retreat proposes the following key positionalities:

- All knowledge is incomplete and can be questioned.

- Acknowledging that diverse perspectives can help overcome obstacles.

- Knowledge and knowledge-creation is contextual.

- Transcending anthropocentric thinking by shifting to organic thinking.

The combination of dialogue and a shared purpose can help us question established definitions of global education, not to add to the list of definitions or dictate the norms, but to encourage the development of inclusive and contextually-relevant approaches to knowledge-creation that ultimately contribute to a more just, peaceful, and environmentally friendly global society.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Johan Estiévenart

Masters student, Faculty of Education, University of Oulu

Masters student of the Education and Globalisation degree programme at the faculty of education, University of Oulu. Former French, English, and history middle school teacher from Belgium. Current research focus is the internationalisation of higher education institutions and employability of (international) degree students.

GENE Awards

EERA is delighted and honoured to be partnering with the Global Educational Network in Europe (GENE) to make significant research funds available to our members to further research in the area of global education.

These research awards are funded by Global Education Network Europe (GENE), the European network of Ministries and Agencies with national responsibility for policymaking, funding, and support in the field of Global Education. For this reason, the subject area for research projects undertaken is that of Global Education.

The purpose of the award is to support quality research around the themes outlined here – which have been identified as of interest to policymakers. Gathering of existing research, application of existing research from other areas of education to Global Education, follow-up studies, all are perfectly acceptable. It is not expected that the research has to draw policy conclusions – but to make available up-to-date, policy-relevant research from which policymaker can draw their own conclusions.

References and Further Reading

Conolly, J., Lehtomäki, E., & Scheunpflug, A. (2019). Measuring global competencies: A critical assessment. ANGEL Briefing Paper.

Lehtomäki, E., & Rajala, A. (2020). Global education research in Finland. The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning; Bourn, D., Ed, 105-120. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/338763792_Global_education_research_in_Finland_Global_education_research_in_Finland