Education is unquestionably the right of all children and it is, therefore, the resolution of all nations to nurture and produce well-educated and intellectually developed citizens. However, for some learners, primarily those who have learning disabilities, studying languages can be even more challenging and time-consuming. Should we ignore these students just because they struggle? Even though they may have difficulties understanding their native language, most are still capable of learning a foreign language.

When we consider the value of English, it becomes even more important for these children to study this language. Given that language acquisition is often regarded as necessary for a brighter future, they shouldn’t be put at a disadvantage in comparison to their classmates and fall behind them.

The concept and practice of inclusive education has gained prominence in recent years. “Inclusive education” aims to end the discrimination brought about by people’s negative attitudes and responses to disparities in ethnicity, social class, language, nationality, sexual identity, religion, disabilities and learning differences as the primary focus of this article.

Neurodiversity

Judy Singer, an Australian autism activist, coined the term Neurodiversity in a thesis published at the University of Technology, Sydney in 1998. In her paper, Singer, clearly defined the term as brain differences, with disorders such as dyslexia being individual deviations from the standard rather than being abnormal. (Singer, 1998).

According to statistics compiled by the International Dyslexia Association, about 13–14 percent of a nation’s student population has a handicap qualifying them for special education needs. About 85% of these students have a main reading and language processing disorder (Dyslexia Basics – International Dyslexia Association, 2014).

However, it’s not clear if teachers know about this term, even about dyslexia or how much they do.

Research into attitudes of EFL teachers towards students with dyslexia

We conducted research in which we asked 100 English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teachers from around the world about their attitudes toward students with dyslexia and whether they felt confident in teaching English as a foreign language to them. These teachers answered the 16-item online questionnaire. When we analysed and compared all of the data, we discovered that a significant number of teachers are unaware of dyslexia, have little training for it, and require additional training to address neurodivergent students. The teachers polled also stated that their countries’ EFL curricula were not designed to meet the needs of students with dyslexia, that the early intervention strategies provided by policymakers were insufficient, and that the majority of teachers were in favour of participating in training programmes on the subject. We agree with Johnston saying that students with dyslexia benefit from explicit, systematic, cumulative, and multimodal instruction that incorporates hearing, speaking, reading, and writing and stresses phonology, orthography, syntax, morphology, semantics, and the organisation of spoken and written discourse. (Johnston, 2019)

We suggest that teachers should be ready to meet the various learning disabilities, and to design engaging tasks, as well as to use established teaching approaches, methods, and efficient teaching techniques. We see it as critical for teachers to understand the problem, how it works, what causes it, and how to solve it.

One of the strategies that have been shown, repeatedly, to provide assistance to individuals who struggle with dyslexia is called mind mapping. Mind maps not only have the potential to help dyslexics with tasks that they may have difficulty with, but they also have the potential to help them become even more successful in the areas in which they already thrive. The user can get assistance with common tasks such as learning, organisation, creative thinking, and more with their use of these tools. So, why not have dyslexic pupils develop mind maps to help them learn a foreign language?

Supporting Neudivergent Students: Using MindMaps

A mind map is a powerful tool that can help the brain to think properly. A mind map, which was first introduced by Buzan, is a diagram with a particular central idea and branches drawn to sub-topics represented by keywords (Buzan, 2006). They have a non-linear shape and can be drawn in vivid colours and with images, which helps retain and memorise information more easily. Neurodivergent students may have difficulty in retaining and processing short-term information, planning and problem-solving skills, memory, perception, motor processing, and information processing speed.

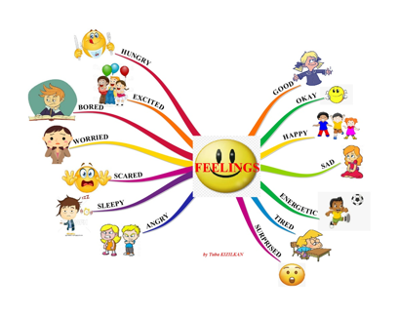

According to Licha, mind mapping continues to be an effective technique for students because it enables them to contextualise material and improve comprehension through the selection of relevant information to record. It has shown to be essential, particularly for older students when revising for exams or taking notes in their classes in a manner that they can comprehend and retain. (Licha, 2020). Here the reader finds an example of a mind map created by one of the authors:

As clearly seen in the mind map above, the interesting images, different colours, a non-linear landscape, keywords, and a circular design that involves both left and right brain hemispheres all help neurodivergent students perceive, understand, and memorise the target information. This is because children who have dyslexia are multidimensional visual thinkers. These students benefit from these types of diagrams when organising thoughts, and solving problems, as a mind map turns monotonous, large amounts of information into manageable chunks of it and central topics with subtopics with only keywords. Categorising information with one or two-word keywords keeps these students on track, as they can easily be overwhelmed by too many words, and it helps them to concentrate.

Besides many advantages of mind mapping, other reasons they work for neurodivergent students such as those with dyslexia are:

- Being able to see the “bigger picture”

- Understanding hierarchy and connections

- Understanding relationships between individual pieces of information

The British Dyslexia Association states in one of its webinars that “Dyslexics struggle with their spoken and/or written language, following instructions, poor concentration and carrying out analytical or logical tasks. Strategies such as mind mapping are recognized as valuable learning tools.” (Link: Webinar: Why Mind Mapping Is Helpful for Dyslexic Learners – An Introduction to Mind Mapping, 2018)

Though Dyslexia has often been regarded as a disability it can be a positive trait that enhances imagination, intuition, intelligence, and curiosity. This is also where mind maps provide an opportunity for students to use their imagination and creativity with their designs. Students enjoy using this learning tool as they can focus on keywords, images, associations, and connections rather than worrying about spelling or grammar. Mind maps in which they can personalise the keywords with associations and images, provide a much more effective and fun way of learning a language. (Frendo, 2019)

We are currently carrying out further research in Turkey with a few pupils who are dyslexic, and the findings will be made public as soon as we have finished analysing them. Teachers should, however, keep in mind that strategies don’t work for every student, and they should adapt these to suit the individual learner.

Key Messages

- Students with learning disabilities may find studying a foreign language challenging and time-consuming

- Research shows that EFL teachers are often either unaware of dyslexia, and may require additional training to help neurodivergent students

- Mind Mapping is a powerful tool for helping neurodivergent students who struggle with retaining and processing information, planning and problem-solving, memory, and perception.

- Mind Maps can be used effectively to help students with dyslexia learn a foreign language.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Ozgu Ozturk

English Teacher

Ozgu Ozturk is an English teacher in Istanbul. She graduated from Gazi University, ELT Department in 2004 and got her MA degree in ELT in 2021. She coordinates Scientix, Etwinning and Erasmus+ international school partnership projects. She is a STEM trainer, P4C facilitator, Dyslexia trainer and educational researcher as an EFL teacher. She is one of the European Climate Pact Ambassadors, Scientix Ambassadors and PenPal Schools Network Ambassadors of Turkiye. She is a National Geographic Educator and a certified Apple Teacher. She is one of the team members of the Education Information Network, EBA which provides digital materials for remote teaching. She is the Turkish delegate on Transatlantic Educators Dialogue by European Union Center and Illinois University at Urbana- Champaign. She is married and has a daughter. She writes blog posts for the international ELT magazine and for the TeachingEnglish blog by the British Council.

Tuba Kizilkan

ELT Professional

Tuba Kizilkan is an ELT Professional who has been teaching English to all age levels for about 21 years. She graduated from Ege University, English Language and Literature Department in 2000. She has also another Bachelor’s degree in International Relations and a Master’s degree in English Language teaching. She is also a Mind Mapping, Speed Reading, and Memory techniques and also an NLP practitioner. She is focused on Linguistics, Neuroscience, and Languages and has been conducting academic research on Linguistics, ELT, Mindmapping, and Education.

References and Further Reading

Buzan, T. (2006). Mind mapping. Pearson Education.

Dyslexia Basics – International Dyslexia Association. (Retrieved: May, 2020). International Dyslexia Association; dyslexiaida.org. https://dyslexiaida.org/dyslexia-basics/

Frendo, A. (2019, March 28). Mind Mapping for Children with Dyslexia. Dyslexic Logic. Retrieved May 2022, from https://www.dyslexiclogic.com/blog/2015/10/30/teaching-mind-mapping-to-children-with-dyslexia

Johnston, V. (2019). Dyslexia: What Reading Teachers Need to Know. The Reading Teacher, 73(3).https://doi.org/10.1002/trtr.1830

Licha, Z. D. (2020). Alternative TEFL Teaching Methods for Dyslexic Students.

Singer, J. (1998) Odd People In: The Birth of Community Amongst People on the Autism Spectrum: A personal exploration of a New Social Movement based on Neurological Diversity. An Honours Thesis presented to the Faculty of Humanities and Social Science, the University of Technology, Sydney, 1998. Accessed February 18, 2015.

Webinar: Why mind mapping is helpful for dyslexic learners – An introduction to mind mapping. (2018, July 30). [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1Lm63Z6EfBc