In human rights law, education is a big deal. A really big deal. It appears in all the major human rights treaties, from the Universal Declaration on Human Rights to the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child. It is said to act as a multiplier of rights, meaning that all other human rights can be enhanced when it is enjoyed fully and impacted negatively when it is not. It is also unique because it is the only right that is compulsory, another indication of how important it is considered to be.

Human Rights and Educational Research

In education and educational research, human rights, particularly children’s human rights, do not enjoy quite such an international ‘Rockstar’ status. While there are a few scholars (none better than EERA’s Network 25)who work explicitly in this area, there is quite a lot of ambivalence and, in some cases, antipathy to human rights (Lundy and Martinez Sainz, 2019). This shows up in the use of language like ‘legalistic’ to dismiss what is often just a sound legal analysis or ‘normative’ to imply that something has no theoretical foundation. And, for the record, what’s wrong with being ‘normative’, especially when those norms are grounded in values derived from centuries of moral philosophy?

An ongoing concern is that there are still those who deny that children can, have, or should have human rights when they would never deny that adults have human rights. I have been told of educational researchers saying that they don’t believe in human rights for children – like they are the tooth fairy. Clearly, they are a legal fact, but a worrying consequence of the resistance to the idea that children have rights has been that the language of children’s human rights can become diluted, substituted and truncated with seemingly ‘safer’ alternatives such as well-being and the SDGs used instead (Lundy, 2019).

A further common response is to talk about how human rights or rights language has been deployed for nefarious purposes or in ways that trivialise their remit and purpose. That is undoubtedly happening (e.g., I am told regularly by teachers that some parents will claim that their child has a ‘right’ to a chocolate bar in a school with a healthy eating policy). However, a sound legal understanding would show that the problem is not the human rights in themselves but a flawed understanding of them. A common example of that in practice is the claim that the rights of the many ‘outweigh’ the rights of the few, particularly when one child’s behaviour is disruptive in a classroom. (Gillett-Swan and Lundy, 2021).

Of course, this is not to say that the human rights laws are perfect articulations of all that we would expect of education. Valid criticisms of human rights law (feminist, post-colonial, neo-liberal etc.) abound. Most come from within our own field, so much so that those of us whose work focuses on children’s human rights have been coined as ‘critical proponents’ Reynaert et al., 2009). Human rights laws are politically negotiated compromises, thus providing fertile soil for critique. The right to education is no exception. States tend not to over-promise, and one result, for example, is that the commitment to free education only applies to primary education, although states should always be striving to improve their provision. Critiquing the standards and therefore the sometimes less than ambitious commitments of governments, drawing in educational research on best practice, is a thriving area of human rights research.

Using human rights law in educational research offers a bounty of other possibilities. For a start, they can provide a conceptual framework for analysis and critique of education policy and practice. Children’s rights policy is distinctly different from childhood policy in substance and in process (Byrne and Lundy, 2018). It demands that the researcher puts their gaze on the child’s interests and entitlements (not just those of the school, teachers, or parents). It is also naturally intersectional – human rights data must be disaggregated, as the focus is always on finding those, particularly those in groups facing discrimination, whose rights might be infringed.

Human rights standards can also be applied to methodology. We have pioneered an approach to research that is guided by the UN Statement of Common Understanding of human rights-based approaches (Lundy and McEvoy, 2012). One consequence of this is that we always work with children as co-researchers, getting their advice on what to research and how to research it. For example, in the recent CovidUnder19 initiative, we took advice from over 270 children across the world about what to ask in a survey of their lives. The children stressed the need to ask about the consequences for examinations and testing in the questions on the right to education. Only children can know what is most important to know from their perspective (Lundy et al., 2021).

The Great Speckled Bird

Photo by Dulcey Lima on Unsplash

In 2004, I moved from a law school to an education school within the same institution. This was not the ‘done thing’. A senior colleague in law warned me that it would not make me a better lawyer. I replied that it would make me a better academic. And I think that we were both right. When I arrived in education, a senior colleague there described me as a bit of a ‘speckled bird’.

In the wave of excitement and optimism, I took it as a compliment, understanding that it meant that I was an interesting addition to the flock. When writing this blog, I decided to investigate the root of that phrase. It turns out that it comes from a southern US hymn and that being a ‘great speckled bird’ is, in fact, not such a good thing:

“Desiring to lower her standard

They watch every move that she makes

They long to find fault with her teachings.”

In truth, sixteen years later, the description of the speckled bird actually makes more sense. Yet, while I work across many fields, and have recently taken up an additional chair in the School of Law at University College Cork, I continue to find a home in the educational research community, benefitting from the fact that education is uniquely and genuinely multi-, inter- and trans- disciplinary.

The Lundy Model – Giving Young People a Voice

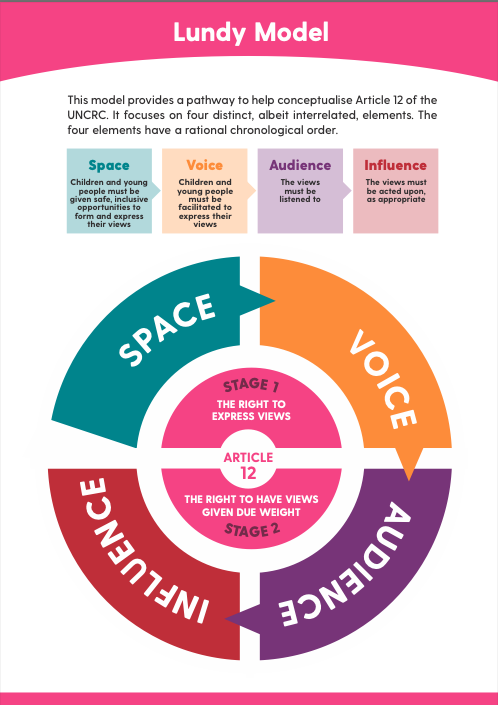

The first education conference that I attended was ECER 2004 in Crete. And it was a result of discussions at that conference that I formulated the rights-based conceptualisation of student voice (space, voice, audience, and influence) that is now widely known as ‘the Lundy model’ (Lundy, 2007).

Human rights law, imperfect as it is, won’t be for everyone, but it has a role to play in understanding why and how we provide education, what it should and shouldn’t look like and how students themselves experience it and can and should shape it. Would we want a world in which there were no human rights, no children’s rights? If not, then we need scholarship that strives to understand its underpinning theory, its content, its limitations and its (lack of) implementation.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Professor Laura Lundy

Professor of Children's Rights, Queen's University Belfast: Professor of Law, University College Cork

Laura Lundy is Co-Director of the Centre for Children’s Rights and a Professor of Education Law and Children’s Rights in the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University, Belfast.

She is joint Editor in Chief of the International Journal of Children’s Rights. Her expertise is in law and human rights with a particular focus on children’s right to participate in decision-making and education rights.

Her 2007 paper in the British Educational Research Journal, “’Voice’ is not enough” is one of the most highly cited academic papers in BERJ and on children’s rights ever. The model of children’s participation it proposes (based on four key concepts – Space, Voice, Audience and Influence) is used extensively in scholarship and practice.

The “Lundy model” has been adopted by numerous national governments and public bodies as well as international organisations including the European Commission, World Health Organisation, UNICEF and World Vision.

References and Further Reading

Irish National Framework for Young Peoples Participation in Decisionmaking

The Framework is based on the child-rights model of participation developed by Professor Laura Lundy, Queens University, which provides guidance for decision-makers on the steps to take in giving children and young people a meaningful voice in decision-making. https://hubnanog.ie/participation-framework/

Universal Declaration of Human Rights

UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.

The role of law and legal knowledge for a transformative human rights education: addressing violations of children’s rights in formal education. Lundy and Martinez Sainz, 2019

A Lexicon for Research on International Children’s Rights in Troubled Times. Lundy, 2019

Children, classrooms and challenging behaviour: do the rights of the many outweigh the rights of the few? Gillett-Swan and Lundy, 2021

A Review of Children’s Rights Literature Since the Adoption of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Reynaert et al., 2009

Children’s rights-based childhood policy: a six-P framework. Byrne and Lundy, 2018

UN Statement of Common Understanding of human rights-based approaches (Lundy and McEvoy, 2012

#CovidUnder19 – Life Under Coronavirus: An initiative to meaningfully involve children in responses to the COVID-19 pandemic. CovidUnder19

Life Under Coronavirus: Children’s Views on their Experiences of their Human Rights. Lundy et al., 2021

‘Voice’ is not enough: conceptualising Article 12 of the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child. Lundy, 2007)