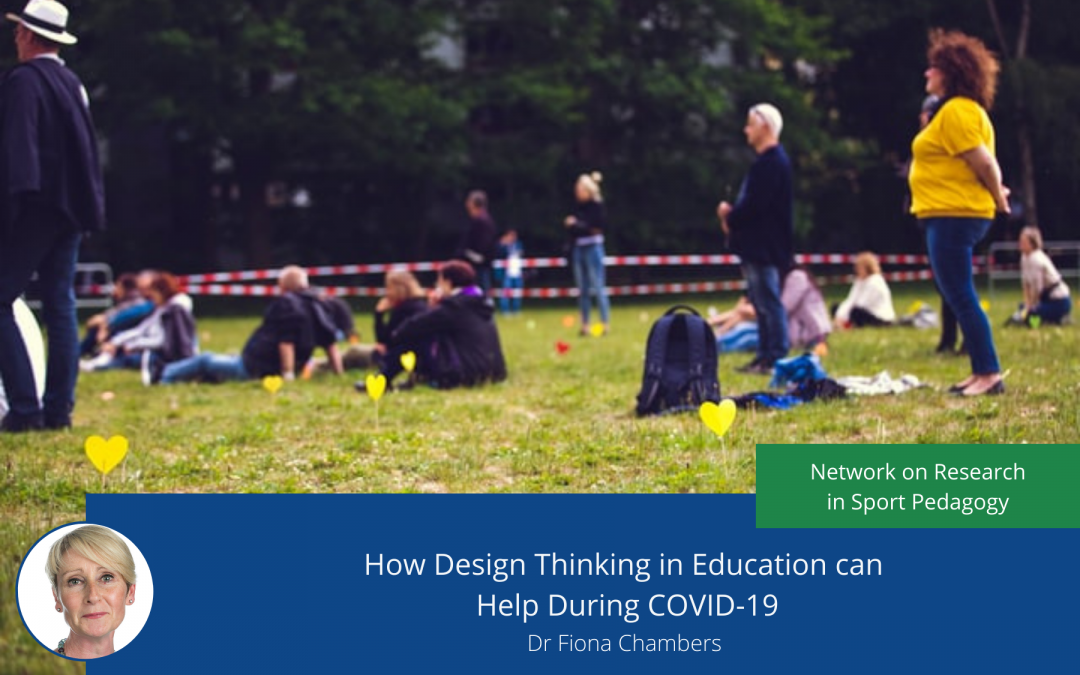

Managing Digital Learning during COVID-19 and Beyond

It is undisputed that Covid has had a massive impact on education and the way it is delivered, both in the UK and internationally. Whilst there have been a number of papers on the ways in which teachers have innovated during this time, and the impact this has had on their workload and mental health, there has been little on how school leaders and their senior teams have taken a strategic overview of online and blended learning. This post takes a look at a funded research project and explores why this area is so important for school leadership, both during the COVID-19 pandemic and beyond.

The recent pandemic has led to unprecedented challenges for school leadership teams and their staff. Almost overnight, they have had to create policies and working practices in a very short timeframe. One leader reported that a strategy meant to take three years had been achieved in three weeks!

In England, secondary schools have been shut down for the duration of two lockdown periods for all but the children of essential workers. Evidence from our pilot project suggests that school leaders have not only changed policies and practices but in many cases, their vision for education. The project, leading school learning through Covid 19 and beyond: online learning and strategic planning through and post lockdown in English secondary schools, investigates how senior leaders strategically planned for online learning – before, during, and after the pandemic. Our sample includes interviews with 70 senior leaders from English secondary schools, along with a questionnaire sent out via project partners to 4000 schools, and an analysis of 200 school websites.

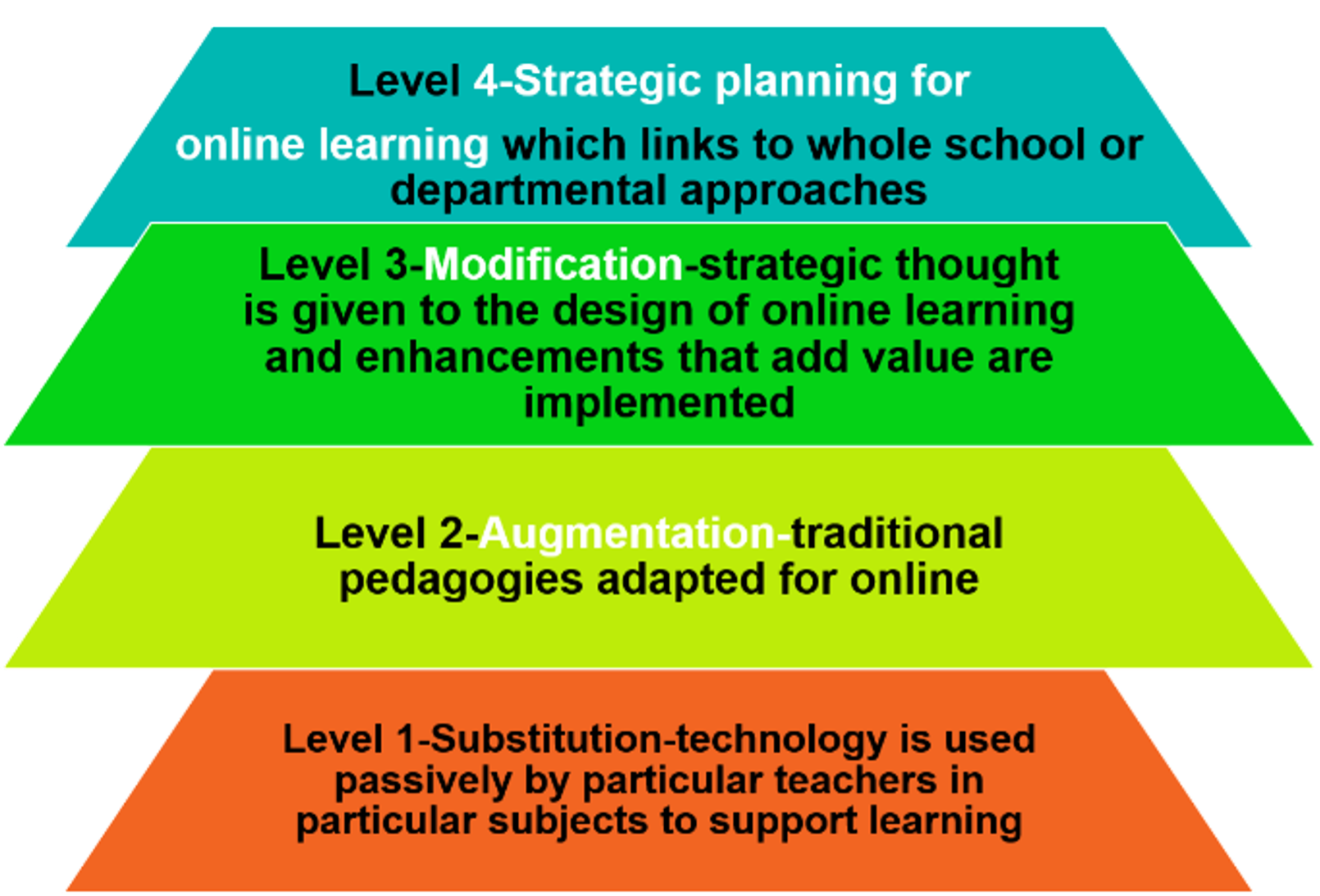

Figure 1 : Strategic Planning for Online learning: Level 1 to 4, adapted from Puntedura, 2021.

Our project classifies the different levels of strategic planning for online education, via an adapted version of Puntedura’s (Puentedura, 2010), SAMR Model, in which the lowest level of planning is termed substitution, the second level is termed augmentation, the third level is termed modification, and the final and most advanced level is termed strategic planning for online learning. (See figure 1). It adopts a strategy as a learning approach which we have used successfully in previous projects relating to educational leadership and management (Baxer & Floyd, 2019; J. Baxter, 2020; J Baxter & John, 2021).

Challenges

Analysis of the pilot project suggests some key themes that are emerging in both qualitative and quantitative data. It is clear that school leaders made some substantial changes to the management of online learning in the period between the first lockdown in March 2020 and the second principal lockdown in the winter of 2020/ 2021. For example, school leaders reported considerable issues with hardware and connectivity, particularly during the first lockdown. Evidence suggests that they have subsequently been creative in acquiring these elements, ensuring that learners were properly equipped to engage with learning during lockdown two.

One of the major categories that has emerged within the study is well-being and care: this in terms of both teacher and learner welfare. School leaders appear to have placed the well-being of their staff and learners first and foremost. They report considerable stress amongst staff, and challenges in relation to learners, particularly those with particular learning needs, and those from lower socio-economic backgrounds. This aligns with the findings of a report by the OECD (Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development).

Leaders have also reported the considerable investment of time needed in building the competencies of parents and carers. This has offered both challenges and opportunities with engaging parents more fully in the learning processes of their children. Communication with parents and learners, and not least in managing online teachers and teams, was also a challenge. Yet again, out of the crisis, there appears to have been some considerable learning taking place, with senior leaders speaking to SEN students and their carers, in some cases on a weekly or even daily basis.

Leaders report that one of the most important tasks during lockdown has been establishing a baseline for effective teaching. Some schools cut down on curriculum to focus on the essentials. Sorting out policies and protocols with staff, governors, and unions, has taken up a great deal of management time, but respondents largely feel that it has been a worthwhile task going forward.

Opportunities

There is considerable evidence of pedagogical innovation and creativity, particularly during the second lockdown when school staff were taken less by surprise. Leaders report evidence of new ideas being tried and tested by teachers, free from the normal constraints. They also report new roles being created as a result of an enhanced focus on digital learning. For example, a new head of digital strategy and innovation at one multi-academy trust; a new head of digital training and development for both teachers and parents in the same MAT.

There is also evidence that some senior leaders are beginning to view education in a different way: one head of a multi-academy trust had already brokered a relationship with Apple to move the whole curriculum online. New and innovative practices adopted during Covid, born out of necessity, are reported as now being ‘business as usual’. An example of this is parent evenings – once held face-to-face and often poorly attended, particularly in schools in challenging areas – which have been much more successful online. Several school leaders state their intention to continue this practice and extend it to governor meetings and, in some cases, staff meetings too.

In terms of quality assurance, this is one area that presented school leaders with their biggest challenges. But from the second lockdown onwards, some schools had already introduced strategies for peer observation of teaching, virtual learning walks, and other innovations to promote and sustain good practice. Some respondents reported using online engagement statistics to measure learner engagement.

One particularly interesting area reported by one senior multi-Academy trust leader: a number of teachers and headteachers across over 15 schools reported that quieter pupils, those who didn’t normally respond well in class, had engaged far more fully with lessons when delivered digitally. This is a potentially intriguing area that could be taken forward concerning introverted students and their more extroverted peers.

Going Forward

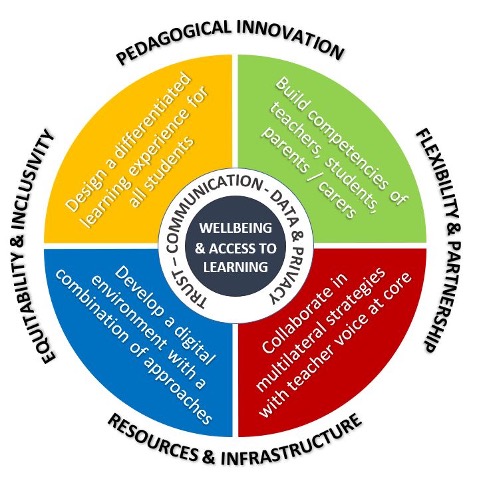

The pilot research has revealed some interesting findings that will be taken forward into the main phase. It has also resulted in a theoretical framework for our research. This is illustrated in figure 2.

As can be seen in the framework, we place well-being and access to learning central to the future development of digital innovation in secondary schools.

The second part of our framework includes:

- designing a differentiated learning experience for students

- the importance of building the competencies of teachers, students, parents, and carers

- collaboration in multilateral strategies with teacher voice at the core

- developing a digital environment via a combination of approaches.

We look forward to continuing our reporting on the project, which will give rise to a free online course for school leaders hosted on the Open University’s open learning platform.

Further details of our project, or to take part, see our website at: https://www.open.ac.uk/projects/leading-online-learning/

or follow us on Twitter at: https://twitter.com/Covid_EduLeader

References and Further Reading

Baxer, J., & Floyd, A. (2019). Strategic narrative in multi‐academy trusts in England: Principal drivers for expansion. British Educational Research Journal, 45(5), 1050-1071.

Baxter, J. (2020). Schemes of delegation as governance tools : the case of multi academy trusts in education under review.

Baxter, J., & John, A. (2021). Strategy as learning in multi-academy trusts in England: strategic thinking in action. School Leadership & Management, 1-21. doi: 10.1080/13632434.2020.1863777

Jewitt, K., Baxter, J., & Floyd, A. (2021). Literature review on the use of online and blended learning during Covid 19 and Beyond. The Open University The Open University

Dr Jacqueline Baxter

Associate Professor in Public Policy and Management The Open University Business School

Dr Jacqueline Baxter is Associate Professor in Public Policy and Management and Director for the Centre of Innovation in Online Business and Legal Education (SCILAB). She is Principal Fellow of The Higher Education Academy, Fellow of The Academy of Social Sciences and Elected Council Member of Belmas. She is outgoing Editor in Chief of the Sage Journal Management in Education (MiE) Her current funded research projects examine the interrelationship between trust, accountability, and capacity in improving learning outcomes; and the strategic management of online learning in secondary schools during and beyond Covid19.

Dr Baxter is based in the Department of Public Leadership and Social Enterprise at the Open University Business School.

She tweets @drjacqueBaxter and her profile can be found at: http://www.open.ac.uk/people/jab899. Her latest book is: Trust, Accountability and Capacity in Education System Reform (Routledge, 2020).

Dr Katharine Jewitt

Research Fellow and Educational Technology Consultant at The Open University

Dr Katharine Jewitt is a Research Fellow and Educational Technology Consultant at The Open University. Katharine works across four faculties (Faculty of Wellbeing, Education & Language Studies, Faculty for Science Technology Engineering and Mathematics, Faculty of Business and Law and The Centre for Inclusion and Collaborative Partnership) and teaches at access, undergraduate and postgraduate levels.

Professor Alan Floyd

University of Reading

Alan Floyd is a Professor of Education and his research and teaching activity focus on two substantive areas: educational leadership and doctoral education. Specific areas of interest include:

- Academic leadership

- School leadership and Multi Academy Trusts (MATs)

- How people perceive and experience being in a leadership role

- Distributed and collaborative leadership

- Leadership development

- Career trajectories

- Identity Insider research and associated ethical issues

- Supporting doctoral researchers