Teacher burnout: Lessons from the aftermath and what helps teachers thrive again

Teaching is one of the most rewarding professions, but also one of the most demanding. Across Europe, nearly half of teachers report experiencing high levels of work-related stress (European Commission, 2021). For some, this stress escalates into teacher burnout, a psychological syndrome marked by exhaustion, emotional detachment, and a reduced sense of personal accomplishment (Schaufeli et al., 2020).

Much of the existing research has focused on the causes of burnout before teachers leave the classroom, and on its consequences once they have dropped out (Ahola et al., 2017). But what happens after burnout, when teachers return to work? Too often, the story ends at the point of absence. Yet the period of reintegration can be just as challenging. Understanding this ‘teacher burnout aftermath’ is essential if schools want not only to support teachers effectively but also to retain them in the profession.

Our study into reintegration after teacher burnout

To address this gap, our study explored the experiences of ten teachers who returned to the classroom after burnout. Using semi-structured interviews, we investigated the challenges they faced and the factors that helped them reintegrate successfully. Although the teachers’ experiences varied, several recurring themes emerged.

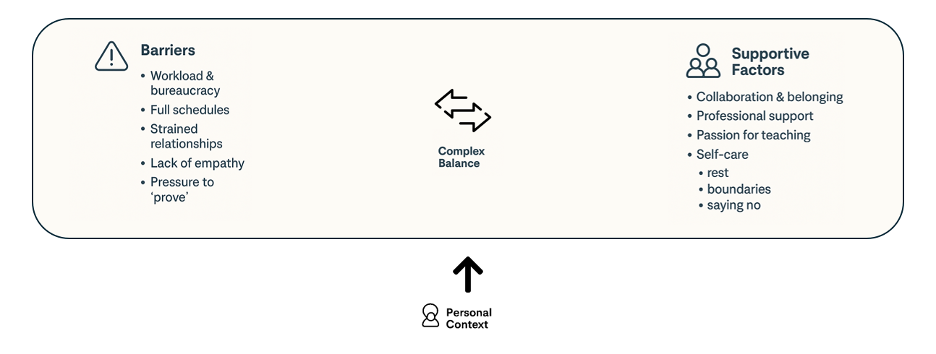

Barriers teachers encounter

Many participants described workload as the most pressing obstacle to recovery. Administrative and bureaucratic tasks consumed precious energy that could otherwise have been invested in teaching. In some cases, schools placed teachers straight back into full schedules, leaving little room to rebuild their confidence.

Relationships also proved decisive. Strained interactions with colleagues or a lack of understanding from school leaders created additional stress. Some teachers reported feeling they had to “prove” themselves all over again, rather than being welcomed back with empathy. This sense of scrutiny often made the return heavier than expected.

Supportive factors that made a difference

Despite these barriers, teachers also pointed to a range of supportive factors that facilitated their reintegration after teacher burnout.

Positive collaboration with colleagues and school leaders created a sense of safety and belonging. Teachers highlighted the importance of professional support, such as therapy, counselling, or coaching, to help them process their experiences. As one participant explained, counselling helped her set clearer boundaries and avoid slipping back into old patterns.

For many, a genuine passion for teaching was a crucial source of motivation: the classroom itself gave them energy and meaning, even if it sometimes carried the risk of overcommitment. Finally, self-care practices such as adjusting workloads, saying “no” more often, or prioritising rest were described as essential in maintaining balance.

Together, these elements created the conditions for teachers to regain stability and gradually rebuild confidence in the classroom.

A complex balance

One of the most striking findings was the dual role of certain factors. Passion for teaching, for instance, could be both a protective resource and a risk. While it inspired teachers to return, it also tempted some to take on too much too soon, undermining recovery.

This highlights the complexity of teacher burnout aftermath: resources and risks are not separate, but deeply intertwined. A factor that enables reintegration in one context can easily become constraining in another. Successful support, therefore, requires continuous adjustment and awareness, rather than one-off measures.

Personal context matters

The study also revealed the decisive role of personal circumstances. Teachers with supportive families or flexible private responsibilities generally found reintegration smoother. Those facing additional stressors, such as caring duties or financial pressures, often experienced a heavier burden.

This underlines that reintegration after burnout is not a one-size-fits-all process but highly context-dependent. Any support strategy must take account of both the professional and personal dimensions of teachers’ lives.

What schools can do

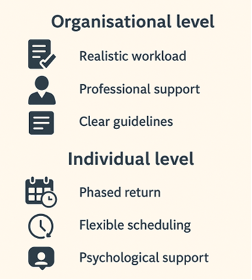

Our findings point to the critical role of school leadership in enabling successful reintegration. Support cannot rely on individual goodwill alone; it requires both organisation-wide frameworks and tailored measures.

At the organisational level, schools should:

- Ensure a realistic workload for returning teachers.

- Provide accessible professional support such as counselling.

- Develop clear reintegration guidelines across the institution, so teachers know what to expect.

At the individual level, reintegration must move beyond a one-size-fits-all approach. Effective measures include:

- Phased returns, where responsibilities are built up gradually.

- Flexible scheduling and the reduction of non-core tasks.

- Access to psychological support.

According to the teachers we spoke to, these personalised adjustments often made the difference between a sustainable return and a renewed risk of burnout.

Moving forward

Reintegration after burnout should not be seen as a private matter for the teacher to “manage better”.

It is a shared responsibility between the individual, the school, and the wider education system.

Addressing both structural and personal dimensions of the burnout aftermath is essential to protect teachers’ well-being and ensure their long-term retention in the profession.

Conclusion

Teacher burnout does not end when a teacher leaves the classroom; in many ways, the story begins there. Returning to work presents its own set of challenges, requiring careful attention, supportive structures, and flexibility. By acknowledging the complexity of the “burnout aftermath” and implementing tailored strategies, schools can help teachers return stronger, healthier, and ready to thrive.

During the ECER conference in Belgrade, we had the chance to connect with fellow researchers and discuss the pressing challenges of teacher burnout. In particular, we explored the gaps in both research and practical strategies for supporting teachers as they return to work after burnout. Hearing their perspectives was incredibly enlightening and highlighted a shared commitment to promoting teacher well-being across diverse educational contexts

Key Messages

- Returning to the classroom after burnout is just as challenging as the burnout itself; it’s a critical but often overlooked phase.

- Workload, strained relationships, and lack of leadership support are major barriers to reintegration.

- Supportive colleagues, counselling, and self-care practices help teachers to return.

- Passion for teaching is both a motivator and a risk, highlighting the complexity of recovery.

- Successful reintegration requires tailored, school-wide strategies that address both personal and professional contexts.

Aron Decuyper

Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University, Belgium

Aron Decuyper is a doctoral researcher at the Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University (Belgium). In his PhD, he focuses on effective teaching behaviour in the context of team teaching. Furthermore, he conducts research on teacher educators and teacher well-being

Laura Thomas

Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University, Belgium

Laura Thomas is a postdoctoral researcher at the Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University (Belgium). Her research focuses on social networks and teacher wellbeing, spanning student teachers, early career teachers, and experienced teachers.

Maxime Moens

Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University, Belgium

Maxime Moens is a doctoral researcher at the Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University (Belgium). Her research focuses on school wellbeing policies, with a particular emphasis on teacher wellbeing.

Melissa Tuytens

Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University, Belgium

Melissa Tuytens is a professor at the Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University (Belgium). Her research and teaching focuses on policy, leadership, and people management in education.

Ruben Vanderlinde

Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University, Belgium

Ruben Vanderlinde is a professor at the Department of Educational Studies, Ghent University (Belgium). He focuses on educational innovation, teacher training and professionalisation and the integration of Information and Communication Technologies in education.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

European Commission/EACEA/Eurydice (2021). Teachers in Europe: Careers, Development and Well-being. Eurydice report. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://eurydice.eacea.ec.europa.eu/sites/default/files/teachers_in_europe_2020_chapter_1.pdf

Schaufeli, W., Desart, S., & De Witte, H. (2020). The Burnout Assessment Tool (BAT) – Development, validity and reliability. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 17(24), 9495. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph17249495

Ahola, K., Toppinen-Tanner, S., & Seppänen, J. (2017). Interventions to alleviate burnout symptoms and to support return to work among employees with burnout: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Burnout Research, 4, 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.burn.2017.02.001