Challenges and Future Directions for Children’s Rights in Education

The Research on Children’s Rights in Education Network (Network 25) recently held our annual event, as part of the European Educational Research Association (EERA) #ReconnectingECER programme.

This was an exceptional event in several respects. Due to COVID and the cancellation of our annual ‘face to face’ European Conference on Educational Research (ECER), we transformed our EERA Network Development funded project into a virtual open event. To broaden exposure to our network, and include a wider range of voices that has not always been possible at previous events, we brought together various communities to encourage intergenerational dialogue that focused specifically on the intersection of education and children’s rights.

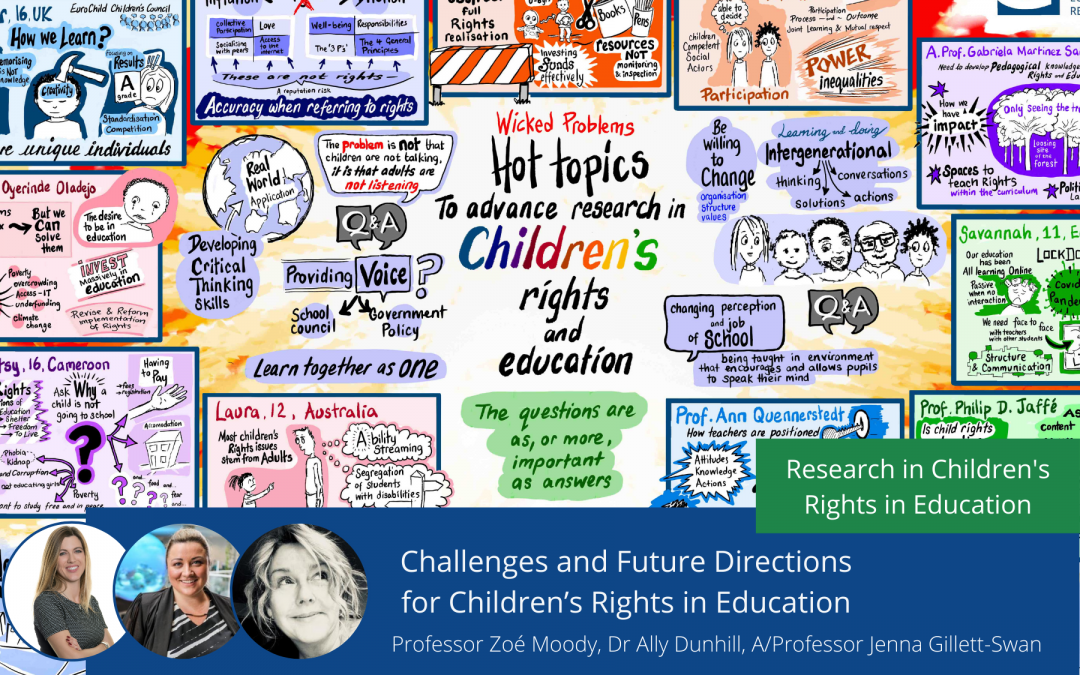

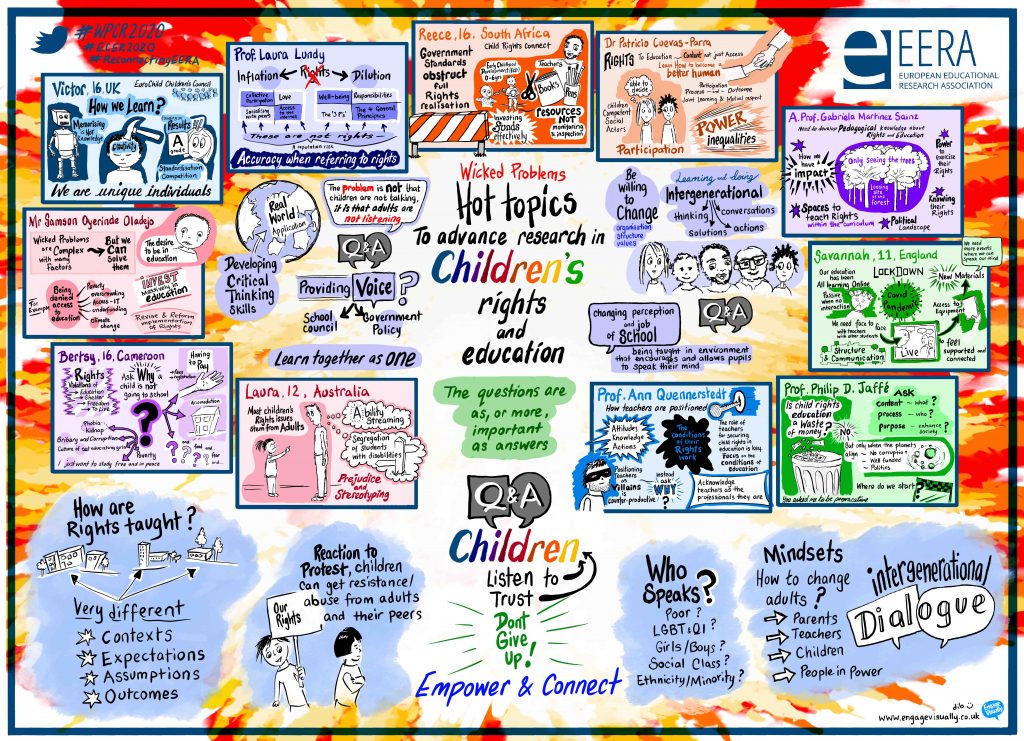

Specifically, the session addressed the topic of “Wicked Problems in Children’s Rights in Education”. We also ensured live-tweeting prior to and during the event through a partnership with @ChildRightsChat. Finally, since we aimed to draw new avenues for research on children’s rights and education, a graphic facilitator accompanied the whole webinar, providing our Network with a visual summary of the discussions initiated.

We were joined by 66 participants from 23 different countries within and outside Europe.[1] 11 presenters provided 11 thought-provoking and stimulating Lightning Talks on different ‘wicked problems’ affecting children’s rights and education. Wicked Problems are problems that are complex or difficult to solve[2].

The speakers comprised of young people and adults, including academics and members of NGOs, from around the world, all passionate experts about child rights and education. The young people brought a unique, lived and living perspective to the topic of ‘wicked problems in children’s rights in education’. Their level of involvement has set a precedent for voice and participation in such discussions.

The Speakers

The event began with Victor, 16 years old from the UK, a EuroChild Children’s Council member. His presentation on ‘The Flaws in our Education System’ set the scene. Victor highlighted the contradiction present in schools, where there is an individualist culture, which simultaneously lacks in consideration for each individual’s uniqueness. The system focuses heavily on memorisation and standardised testing, which stands in contrast to individualism.

Professor Laura Lundy, from Queen’s University Belfast, followed with ‘Children’s Rights – Inflation, Dilution and Reputation’. Professor Lundy shared her thoughts on how and when the actual language of the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child is used. She argued that legal accuracy is necessary to ensure credibility in the field of children’s rights and education.

We heard then from Bertsy, 16 years old from Cameroon, a member of the GNRC Youth Committee – Arigatou International in 2019. Bertsy provided us with examples of how the costs of education, notably school fees, impact the most vulnerable in societies. By doing so, she raised the issue of who contributes to enforcing rights in such contexts.

Mr Samson Oladejo, a PhD Candidate at the University of the West of Scotland, then reminded us of the number of children not in education and how technology could support many of these children’s needs. Mr Oladejo provided examples from his research focusing on discourses of risk that obfuscate educational access (in the context of Universal Basic Education) for young people in poor urban areas of Lagos, Nigeria.

Laura, a 12-year-old Australian and founder of Student Alliance 4 Inclusion, then concluded the first section of the Webinar with a presentation titled ‘Adults’ assumptions on segregating children in education -the discriminatory legacy for children’. She made the point that discriminating against children in education does not meet the requirements of article 29 of the UNCRC and drew upon specific examples of disability discrimination and segregation in educational contexts.

After a short break, Dr Patricio Cuevas-Parra, the Director for Child Participation and Rights with World Vision International, launched the second section of the Webinar. Dr Cuevas-Parra provided examples of how adults need to ‘share the platform’ with children and young people, and how ‘power’ can have a diverse impact on how the platform is shared. He insisted on the fact that empowerment is a process and an outcome. You can read Dr Patricio Cuevas-Parra’s blog post here.

Following this, we heard from Reece, a 16-year-old South African, Child Rights Advisor with Child Rights Connect, and founder of Earth Kids Organisation (EKO), which focuses on environmental education and youth empowerment projects. Reece’s talk concentrated on early childhood development and rights. He illustrated how governmental standards can sometimes undermine rights and problematised the longer-term implications of such restrictions.

Our next speaker, Assistant Professor Gabriela Martinez Sainz, an Ad Astra Fellow and Assistant Professor in Education at University College Dublin, called for more research on pedagogical knowledge on children’s rights. She also pointed out the lack of ‘structures and spaces’ to teach children about their rights.

Savannah, 11 years old from England is a Child Rights Advisor with Child Rights Connect. She provided us with examples of some of the issues children had during the COVID-19 school closures. Ending with a plea for all children to have ‘real and regular’ contact with teachers during such times, Savannah highlighted the difficulties of going through education ‘alone’.

Our penultimate speaker was Professor Philip D. Jaffé, from the Centre for Children’s Rights Studies (CCRS) and current member of the Committee on the Rights of the Child. Professor Jaffé provided us with an ecological understanding of Human rights violations. Witnessing the numerous violations of children’s rights within education, he provocatively wondered whether human rights education remains possible if this does not change.

Professor Ann Quennerstedt, from Örebro University in Sweden and Link Convenor of Network 25 was our final speaker. Professor Quennerstedt stated that ‘Teachers are a wicked problem’ and reminded us that ‘positioning teachers as villains’ does not support children’s right in education. She suggested child rights researchers should turn the focus away from teachers to address structural issues and aspects of professionalisation.

The Discussions – A Visual Representation

There was a wide range of insightful questions from the attendees and the presenters did an excellent job of answering these questions from attendees verbally and in the chat. We were delighted to have Debbie Roberts from EngageVisually joining us this year.

Debbie created a visual summary of the event by way of a graphic recording. This visual has captured the essence of the talks and exchanges that occurred during the session. At different points throughout the seminar, we were able to see the ‘work-in-progress’ which further stimulated our ongoing conversations.

Feedback from Attendees

‘An absolutely excellent session. I found it to be very educative in the widest sense in the re-visiting foundational principles from unique and diverse perspectives and then expanding upon them even more. Few webinars have left me so enriched.’

– Regina Murphy, DCU, Ireland.

‘I really enjoyed the conference. Very well organised and fantastic speakers. The intergenerational dialogue was rich and meaningful.’

– Panellist Dr Patricio Cuevas Parra, World Vision International

Future Activities

The event has generated much discussion, new ideas, and collaborative possibilities, which we, as a network, will continue to cultivate in our future activities. Among the numerous options evoked, we are pleased to share here a few take-aways:

- Research directions

- Ask more WHY questions to understand the reasons undermining rights implementation in education (versus solely describing them)

- More interdisciplinary work to reinforce the human rights language used in research in Children’s rights and education without losing the focus on core educational questions

- Research topics

- How the COVID crisis affects education beyond lockdown, and seeking children’s own views on these matters?

- The abuse and bullying of children activists

- What are the aims of education?

- Research collaborations:

- Including more intergenerational dialogue

Find out details of these activities through subscribing to our newsletter and following the network via Twitter@Network25EERA.

To subscribe to the network newsletter, simply send a blank message to nw25-subscribe@lists.eera-ecer.de

Finally, we recommend looking for the following accounts and hashtags on Twitter, to read some of the interesting anecdotes and discussions from the event:

- @ChildRightsChat (who were live-tweeting the event)

- @Network25EERA

- @ECER_EERA

- #ReconnectingEERA

- #WPCR2020

- #ECER2020

Sponsors

Our event was proudly supported by EERA’s Network Development project funding scheme. We want to thank our supporters EERA and @ChildRightsChat, for having made this event possible. Thanks also to the University of Geneva, and its Centre for Children’s Rights Studies for technical support. We would also like to express our sincere thanks and gratitude to the following organisations who have supported the event with enthusiasm and a short timeframe to initiate young people’s participation in the event, namely: Child Rights Connect; Eurochild; Time-matters UK, and Arigatou International.

[1] Australia, Bangladesh, Belgium, Cyprus, Finland, France, Georgia, Germany, Hungary, Ireland, Israel, Italy, Moldova, Norway, Poland, Rwanda, Sweden, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, United Kingdom, Turkey and USA.

[2] For additional insight on ‘wicked problems’ see B. Guy Peters (2017) What is so wicked about wicked problems? A conceptual analysis and a research program, Policy and Society, 36:3, 385-396, DOI:10.1080/14494035.2017.1361633

Professor Zoe Moody

University of Teacher Education Valais

Zoe Moody is Professor at the University of Teacher Education Valais and Senior Research Associate at the Inter- and Transdisciplinarity Unit, Center for Children’s Rights Studies, University of Geneva. Her research and teaching activities lie at the intersection between educational sciences and the field of children’s rights: notably children’s rights to, in and through education. Zoe Moody is French-speaking editor of the Swiss Journal of Educational Research and Deputy link convenor of the Research on Children’s Rights in Education Network (25) of the European Conference on Educational Research (ECER).

Dr Ally Dunhill

Dr Ally Dunhill is a consultant and researcher in the social policy domain, with a particular focus on children, youth, inclusion and rights. She has worked across the education and social care sectors for over 30 years. She has lectured, researched and presented on a wide range of topics, all with the core theme of promoting, protecting and respecting human rights. Since 2015, all aspects of her work have been aligned to the Sustainable Development Goals (SGDs). Ally is also the co-founder of Accessible AD, one of the first Start-Ups in the UAE, which is a third sector organisation focused on accessibility and inclusion.

Jenna Gillett-Swan

Associate Professor, Faculty of Education at Queensland University of Technology, Australia

Associate Professor Jenna Gillett-Swan researches to understand and address threats to wellbeing in students’ educational experiences through participatory rights-based approaches to educational transformation and school improvement. A/Prof Gillett-Swan’s approach is characterised by privileging the perspectives and experiences of young people and working in partnership with them and other stakeholders to enact change and influence in educational contexts. She is an Associate Professor within the Faculty of Education at Queensland University of Technology, Australia; co-leader of the ‘Safety and Wellbeing’ research program within the Centre for Inclusive Education; a member of the International Journal of Children’s Rights Advisory Board, and current co-convenor for the European Educational Research Association Research on Children’s Rights in Education Network.