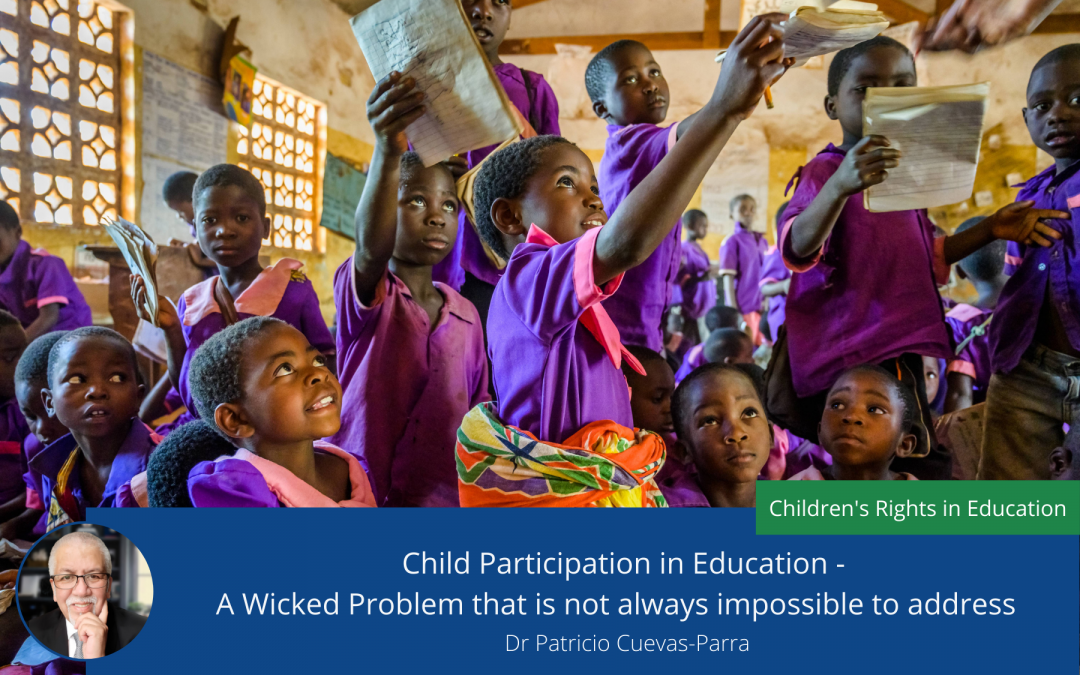

The Rights of Children in Education

Some weeks ago, I was invited to deliver a speech at the ‘Wicked Problems in Children’s Rights in Education’ conference organised by the European Educational Research Association. Whilst preparing my talking points, I was reflecting on the fact that a ‘wicked problem’ is one that is difficult to resolve. There is no simple solution to a wicked problem and it creates tensions, depending on the lens used to analyse the issue. Within this context, I decided to throw some light on one of the more radical rights outlined in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC): children and young people’s right to participate and its intersection with the right to education.

The UNCRC has been recognised as revolutionary because, for the first time in history, it entitled children and young people with a specific set of human rights, including the right to participate. The UNCRC’s views deem children and young people to be rights-holders and is supported by the childhood studies field that positions them as competent social actors. However, three decades after the UNCRC entered into force, participation rights continue to be challenging to implement, and the educational system is no exception.

In order to discuss these issues, it is critical to review three key global policy instruments:

- the UNCRC

- the UN’s Committee on the Rights of the Child (CRC’s) General Comment No. 1 on the aims of education

- the CRC’s General Comment No. 12 on the right to be listened to.

The Aims of Education

General Comment No.1 highlights that education is not only composed of the formal schooling system, but it should also include the development of life experiences and learning processes to strengthen children and young people’s personalities, talents, and abilities. In the same line of thought, the UNCRC’s Article 29 outlines the aims of education as the holistic development of children and young people’s full potential, including the development of respect for human rights, an enhanced sense of identity and socialisation, and interactions with others and the environment. Thus, children and young people’s right to education is not only a matter of access; it is also about content, which must be child-centred, child-friendly, and empowering.

Unfortunately, children and young people’s experiences in many educational systems around the world reveal that these aims are not always achieved. Often the focus is only on improving academic skills and sharpening intellect, ignoring other critical formative components. Here is where education systems’ aims contrapose UNCRC’s ideals, including the promotion of children and young people’s empowerment, as stated in General Comment No.1 and the UNCRC’s Article 12.

Empowerment can be achieved by developing children and young people’s social skills, supporting learning and other capacities, valuing human dignity, and supporting self-esteem and self-confidence. This raises the question of whether this aim is attained or undermined by the systemic focus on academic success.

The Right to Participate

In turning the discussion to children and young people’s right to participate, defined by General Comment No. 12 as ‘the right to express their views freely in all matters affecting them’, an ‘ongoing process, which includes information-sharing and dialogue between children and adults based on mutual respect’. This definition embraces the notion of participation as a process with three pivotal components:

- an impact on decision-making

- mutual respect between children and young people and adults

- a collaborative learning process.

The Disconnect between Rights and Reality

Now, where is the tension? What makes the implementation of this right to participate in education problematic? Children, as rights-holders, competent social actors, and empowered decision-makers, should be able to have opportunities to form and express their views freely, and these views should be respected and taken seriously. However, reality shows that children and young people seldomly have meaningful opportunities to participate in decision-making processes at school, and they rarely perceive positive results from their participation.

The major constraints are consistently the same across time and spaces:

- the authority of adults, in this case, school teachers and educational staff, over children and young people that perpetuates patriarchal structures of power

- inequalities in education which includes or excludes children and young people based on their social categories

- tensions between children and young people being considered objects of education and subjects of mutual learning.

Yet, this ‘wicked problem’ can be easily addressed, if all parties involved take the key principles outlined in the UNCRC, General Comment No. 1, and General Comment No. 12 seriously.

Hence, in order to discuss the future direction needed to ensure the realisation of children and young people’s rights, we must link participation rights and education aims when designing educational systems. Children and young people must be front and centre as subjects of rights, subjects of learning, and competent social actors, able to shape their educational environments. The challenge will always be to create spaces where adults listen to children and young people and take their views seriously. Thus, adults also need to build their abilities to listen to children and young people and adapt their decision-making processes to be more inclusive and equitable.

Photo Credit: World Vision/Jon Warren

Dr Patricio Cuevas-Parras

Director for Child Participation and Rights with World Vision International

Dr Patricio Cuevas-Parra is the Director for Child Participation and Rights with World Vision International. He leads strategies and programmes to ensure that children and young people are at the centre of the advocacy and policy debate.

He holds a PhD in Social Policy from the University of Edinburgh, United Kingdom, a Master of Advanced Studies in Children’s Rights from University of Fribourg-UIKB, Switzerland, and a Master of International Relations. Patricio has worked in more than 20 countries, including long-term roles in Ecuador, Chile, Indonesia, Lebanon, Cyprus and the United Kingdom. He has published a variety of books and reports on the topics of children’s rights, child participation, indigenous children and gender equality.

Dr Cuevas-Parra has a keen interest in looking at cutting-edge child rights advocacy tools and models to enhance children and young people’s engagement in decision-making. His research interests fall into three main categories: children’s participation in public policy, child-led research methodologies, and children’s perspectives on violence and abuse. Patricio is currently conducting research projects on children’s participation with Queen’s University Belfast and the University of Edinburgh.