Language scaffolding as a complex craft

Worldwide, an ever-increasing number of students undertakes (part of) their education in a second language.[1] And although Dutch exceptionalism would sometimes like us to believe otherwise, this development is also visible in the Netherlands.[2] Language–focused subject education is tailored to these multilingual educational contexts, as it supports specific knowledge and skills, as well as language development. [3][4] Nevertheless, a focus on language is not always an integral part of subject teachers’ teaching in multilingual environments. [5] Yet, very few studies have focused on the kinds of support that are provided.

Our research examines the types of language support teachers in Dutch bilingual secondary education do provide and the reasons they have for providing it. In these multilingual settings, the languages of instruction are Dutch and English. [6]

The Dutch Network of Bilingual Schools currently has more than 130 members [7] and most of the schools follow a curriculum that is similar to non-bilingual schools. The national curriculum guidelines include elements of citizenship education in subjects such as geography. Comparing practices across citizenship-related subjects [8] [9] allows for comparisons across schools and classrooms.

We asked eight teachers across four schools about the ways they support learning through English in their classrooms. We observed three lessons by the first seven teachers, and two lessons by the last one. After observing the lessons, we used Stimulated Recall Interviews to discuss the observed instances of language scaffolding to ask about their motivations for providing these types of support. We are currently trying to make sense of this data by using the concepts of whole-class scaffolding, language levels and scaffolding motivations.

We believe that these two examples make three important points. First, teachers do support students’ writing assessments. Second, when they do, it is not only for language or content reasons, but also for reasons related to disciplinary or broader academic literacy. Third, and perhaps most importantly, we need to view teaching as a complex craft where teachers do sometimes engage beyond the word level to help their students to create complex texts.

Perhaps they do not engage in these supports constantly. Perhaps it would be better if they did it more often. Perhaps we should just appreciate the language supports teachers manage to provide in demanding classroom environments where language support is one of the many important educational and psychological student needs that require attention at various moments. We believe that rather than dividing teaching up into checkboxes and deliverables, we should keep investigating the things teachers do well so that we can understand them better and spread good practices.

What is scaffolding?

Scaffolding is a rather contentious concept. [10] [11] Within this research, scaffolding is understood as a process by which a teacher responds to students’ needs by gradually adding support. By focusing on the type of scaffolding that helps students to continue with a difficult task individually, we are able to look at language support in both a focused and a broad way. [12]

The language part of language scaffolding is covered by language levels, as teachers modify their language support according to the varying needs of the students. In this way, we can see whether the scaffold is geared towards the word, sentence or text level, and also whether students are helped in more active or passive skills. [13]

Finally, we were interested in scaffolding motivations, or the reasons teachers have to engage in language scaffolding, whether it is to support students’ language or content development or disciplinary literacy. [14] Whereas content development refers to assisting students in coping with the subject matter, disciplinary literacy is about ‘learning to think like a historian, mathematician, […]’ [15], or in this case, like a social scientist.

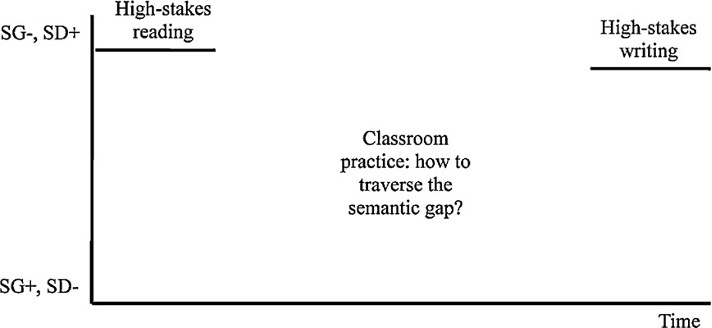

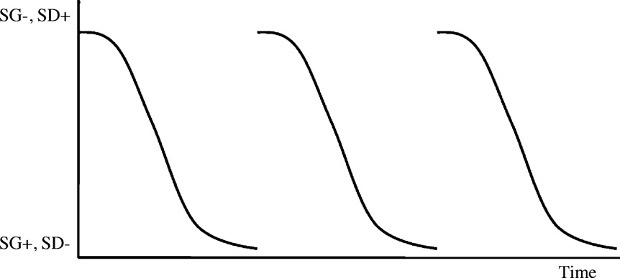

A common problem for teachers in contexts is bridging the gap between the knowledge that students access through reading in class, and the type of knowledge they must display in written assessments. [16] After the work of Maton and others, we use the word unpacking to refer to the process by which a teacher helps students to access knowledge. Repacking is used to describe the process by which a teacher helps a student to display this knowledge in writing. [17]

Maton, 2013, p. 14

As in previous research, [18] rather than supporting students in producing difficult texts, our teachers mostly support the ways students access knowledge and help them to unpack difficult concepts.

Maton, 2013, p. 14

Examples of Repacking

Although this is an interesting finding in itself, some teachers do repack. And they do so not just for language or content reasons. Let me illustrate this with two examples, both from geography classes.

When asked about their language scaffolding practices, the first teacher describes a situation where they help students to answer questions.

‘… the kids write their answers on the board, and I go, okay: this is a peer review and how can we look at improving …the style of answering, the method of answer.

Where is the piece of information, where is the point of information we want, where is the next point? We are looking, we are coming back and highlighting: this is what the question is asking, this is the question word, this is the question phrase, this is the term, have we answered and seen these two question terms in your answer, build it up, and they write.’

We believe that this illustrates that this teacher is engaging in repacking as they help the students to formulate answers to difficult questions. And when asked about the reasons for engaging in this type of language scaffolding, they state that it is about ‘building up a habit’ and ‘how they understand my subject’.

In the second instance, another teacher describes the scaffold they provide for writing an essay.

‘I mainly use the interaction with the class to decide what goes up on the board. So the points, the explanations, and the examples are put on the board…

And for that, I took a number of slides I got from an English teacher with all kinds of linking words and asked them: ‘how can you link these sentences?’

So first, I showed them on the screen what the class already knew, these are also words that you can use to make this link, and also what should be in your final conclusion, what should be in there?’

And this teacher also does not see this instruction as something that focuses solely on language or content:

‘I don’t necessarily think it’s subject specific, I really think it’s quite general. I think most subjects use that [point-example-explain, ed.] structure. I do make my assignments so that this can be integrated so that I can help with this.’

Key Messages

- Language supports are important for a variety of educational contexts

- Teaching is a complex craft where teachers attend to many important educational and psychological student needs

- A framework combining whole-class scaffolding, language levels, and scaffolding motivations can provide insights into the ways language scaffolds unfold in classrooms

- Teachers support students’ writing assessments beyond language or content, including disciplinary or broader academic literacy

- Finding out what teachers do, rather than what they should be doing can contribute to spreading good practices

Errol Ertugruloglu

Ph.D. student at Leiden University, Leiden, the Netherlands.

Errol Ertugruloglu is a Ph.D. student at Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching (ICLON). His background is Political Science (BSc. and MSc.). His doctoral research investigates the ways subject teachers support language in multilingual educational settings in the Netherlands. Among other things, he is interested in multilingual education, migration, and classroom practices.

[1] Jessica G. Briggs, Julie Dearden, and Ernesto Macaro, “English Medium Instruction: Comparing Teacher Beliefs in Secondary and Tertiary Education,” Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching 8, no. 3 (August 27, 2018): 673–96, https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2018.8.3.7

[2] Emmanuelle Le Pichon-Vorstman and Sergio Baauw, “EDINA, Education of International Newly Arrived Migrant Pupils,” European Journal of Applied Linguistics 7, no. 1 (February 28, 2019): 145–56, https://doi.org/10.1515/eujal-2018-0021.

[3] Adam Tyner and Sarah Kabourek, “Social Studies Instruction and Reading Comprehension: Evidence from the Early Childhood Longitudinal Study” (Thomas B, September 2020), https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED609934.

[4] Joana Duarte, “Translanguaging in Mainstream Education: A Sociocultural Approach,” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 22, no. 2 (February 17, 2019): 150–64, https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1231774.

[5] Huub Oattes et al., “Content and Language Integrated Learning in Dutch Bilingual Education: How Dutch History Teachers Focus on Second Language Teaching,” Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics 7, no. 2 (December 31, 2018): 156–76, https://doi.org/10.1075/dujal.18003.oat.

[6] Tessa Mearns and Rick de Graaff, “Bilingual Education and CLIL in the Netherlands: The Paradigm and the Pedagogy,” Dutch Journal of Applied Linguistics 7, no. 2 (December 31, 2018): 122–28, https://doi.org/10.1075/dujal.00002.int.

[7] Nuffic, “Alle Tto-Scholen in Nederland,” accessed January 24, 2023, https://www.nuffic.nl/onderwerpen/tweetalig-onderwijs/alle-tto-scholen-in-nederland.

[8] Wolfram Schulz et al., IEA International Civic and Citizenship Education Study 2016 Assessment Framework (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2016), https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-39357-5 (p. 97).

[9] Margarita Ivanova Jeliazkova, “Citizenship Education: Social Science Teachers’ Views in Three European Countries” (PhD, Enschede, The Netherlands, University of Twente, 2015), https://doi.org/10.3990/1.9789036540056.

[10] Janneke van de Pol, Monique Volman, and Jos Beishuizen, “Scaffolding in Teacher–Student Interaction: A Decade of Research,” Educational Psychology Review 22, no. 3 (September 1, 2010): 271–96, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-010-9127-6.

[11] Esmaeel Hamidi and Rafat Bagherzadeh, “The Logical Problem of Scaffolding in Second Language Acquisition,” Asian-Pacific Journal of Second and Foreign Language Education 3, no. 1 (December 2018): 19, https://doi.org/10.1186/s40862-018-0059-x.

[13] Jantien Smit, Henriëtte A. A. van Eerde, and Arthur Bakker, “A Conceptualisation of Whole Class Scaffolding,” British Educational Research Journal 39, no. 5 (October 2013): 817–34, https://doi.org/10.1002/berj.3007.

[13] Y. Y. Lo and A. M. Y. Lin, “Designing Assessment Tasks with Language Awareness: Balancing Cognitive and Linguistic Demands,” 2014, http://hub.hku.hk/handle/10722/213641.

[14] E Ertugruloglu, T Mearns, and W Admiraal, “Scaffolding What, Why and How? A Critical Thematic Review Study of Descriptions, Goals, and Means of Language Scaffolding in Bilingual Contexts,” accessed January 24, 2023, Manuscript submitted for publication.

[15]Steven Z. Athanases and Luciana C. de Oliveira, “Scaffolding Versus Routine Support for Latina/o Youth in an Urban School: Tensions in Building Toward Disciplinary Literacy,” Journal of Literacy Research 46, no. 2 (June 2014): 263–99, https://doi.org/10.1177/1086296X14535328.

[16] J.R. Martin, “Embedded Literacy: Knowledge as Meaning,” Linguistics and Education 24, no. 1 (April 2013): 23–37, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2012.11.006.

[17]Karl Maton, “Making Semantic Waves: A Key to Cumulative Knowledge-Building,” Linguistics and Education 24, no. 1 (April 2013): 8–22, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2012.11.005.

[18]Yuen Yi Lo, Angel M. Y. Lin, and Yiqi Liu, “Exploring Content and Language Co-Construction in CLIL with Semantic Waves,” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, August 30, 2020, 1–22, https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2020.1810203.