Conferences as catalysts for researcher development: Lessons from Post-Soviet contexts and reflections from ECER

What does it truly mean to attend a conference? Is it merely about collecting certificates and adding lines to a CV, or does it represent a deeper professional journey? My experience at European Conference for Educational Research (ECER) and several other conferences I have attended since beginning my PhD in the United Kingdom have helped me answer these questions and reflect on the challenges faced by researchers in post-Soviet contexts.

Two journeys, two systems

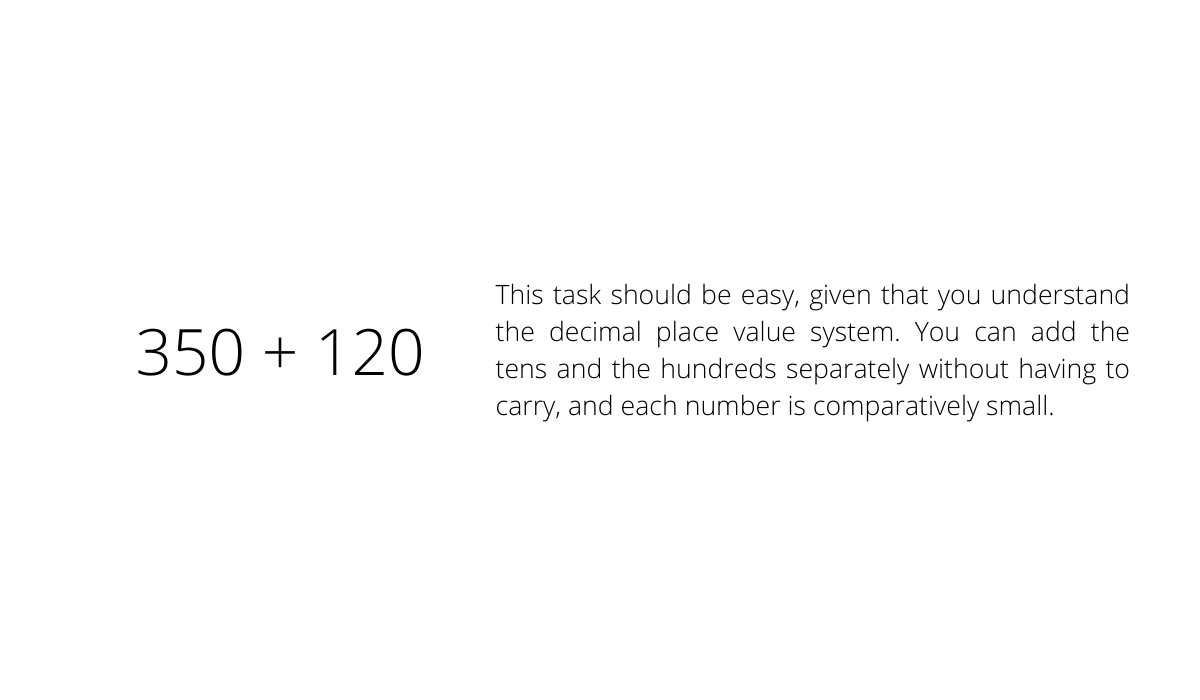

When I first arrived in the UK to begin my PhD, I carried with me a clear formula for academic success: academic achievement = conferences + publications. That belief originated from my first PhD experience in Azerbaijan, where the rules were explicit, three conferences (one international) and five articles, or no degree. While there was comfort in that structure, it also brought pressure. Conferences were obligations, not opportunities.

Interestingly, my supervisors in the UK encouraged a different approach: “One meaningful conference is better than five rushed ones.” Initially, this lack of rigid targets and checklists left me uncertain about how to measure progress. However, over time, I came to understand the depth of their advice.

Predatory publishing and Soviet legacies

Recent scholarship on post-Soviet academic systems highlights the persistence of Soviet-era evaluation practices that prioritise quantitative output over research quality (Chankseliani, Lovakov & Pislyakov, 2021). This study examines how such legacies shape publishing behaviours and contribute to the growth of predatory publishing in post-Soviet educational research. How many conferences? How many articles? How many citations? This system rewards quantity rather than quality, perpetuating a cycle of superficial productivity.

Predatory publishers – organisations that charge fees for publishing work without proper peer review – and “fast-track” conferences thrive under such conditions. In Azerbaijan, Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan, and beyond, early-career researchers are often lured into prestigious-sounding “Global Innovations in Science” events hosted in Paris or Dubai, high fees, impressive certificates, but minimal academic substance (Hajiyeva, 2023). The pursuit of legitimacy can make researchers vulnerable to academic exploitation.

Scholars such as Kulczycki (2017) and Chankseliani et al. (2021) have demonstrated that bibliometric inflation is widespread across the region. Academic worth is frequently reduced to numbers, a lingering legacy of Soviet-era evaluation frameworks, where scientific labour was planned, counted, and reported for administrative purposes rather than genuine inquiry. Although policy language has evolved, institutional cultures often remain unchanged. Weak research infrastructure, limited funding, insufficient training in empirical methods, and minimal collaboration all contribute to a cycle of formality without substantive innovation (Kuzhabekova & Mukhamejanova, 2017; Ruziev & Mamasolieva, 2022).

Insights from ECER

Unlike the so-called “international” conferences I had previously encountered, often held in tourist capitals with grand titles but little academic value, ECER offered a genuine academic community. My presentation was peer-reviewed, the audience posed thoughtful questions, and the true value lay in the scholarly exchange rather than the certificate.

One notable aspect I observed, rarely discussed openly before, was the element of care. ECER made deliberate efforts to support researchers with children. Although childcare remained costly compared to my experience at the ESA 2024 conference in Porto, the recognition of this issue was an important step. Inclusion, I realised, is not merely a research topic; it must also be a lived academic practice.

Through these experiences, I learned that conference participation should not be treated as a numerical pursuit. It is a long-term dialogue, a slow process of building academic identity. Attending one or two high-quality conferences per year, combined with collaborative projects and research visits, can be far more valuable than accumulating numerous certificates.

My advice to early-career researchers, particularly those from post-Soviet contexts, is this: do not chase appearances, seek scholarly communities.

Conclusion

To truly support researcher development, academic systems should:

- Shift evaluation criteria from quantity to depth.

- Reward collaboration and intellectual contribution, not mere output.

- Strengthen research literacy to resist predatory academic practices.

Until academic value is redefined in this way, research systems will continue to produce numbers instead of knowledge.

Conferences, when grounded in genuine scholarly exchange rather than numeric performance indicators, can serve as spaces of both personal and systemic transformation. For post-Soviet researchers, embracing this perspective may be crucial in redefining academic success and fostering authentic research cultures.

Key Messages

- Conference participation is not just about certificates or CV lines—it is a meaningful journey of professional and personal growth.

- Academic systems in post-Soviet countries often prioritise quantity over quality, which can lead to superficial productivity and vulnerability to predatory publishing and conferences.

- Genuine scholarly communities, such as those fostered at ECER, offer opportunities for peer review, intellectual exchange, and inclusion—far beyond what “fast-track” conferences provide.

- Researcher development benefits most from attending a few high-quality conferences, engaging in collaborative projects, and building authentic academic networks, rather than chasing appearances or numbers.

Turan Abdullayeva

University of Sheffield

Turana Abdullayeva is a PhD researcher in Education at the University of Sheffield and an Associate Fellow of the Higher Education Academy (AFHEA). Her research focuses on inclusive education, decolonial disability studies, and teacher education in post-Soviet contexts, with a particular emphasis on Azerbaijan.

Alongside her doctoral work, Turana teaches and supervises postgraduate students, contributes to international research projects on accessibility and anti-ableist research cultures, and works in student support and inclusion. She has published in leading international journals, including Disability & Society and the International Journal of Inclusive Education, and regularly writes reflective blog posts on academia, access, and belonging.

Linkedn: www.linkedin.com/in/dr-turana-abdullayeva-9456961a1

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Chankseliani, M., Lovakov, A., & Pislyakov, V. (2021). A big picture: bibliometric study of academic publications from post-Soviet countries. Scientometrics, 126(10), 8701-8730. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/353979277_A_big_picture_bibliometric_study_of_academic_publications_from_post-Soviet_countries

Hajiyeva, N. U. (2025, August 31). Facebook post. Retrieved September 15, 2025, from https://www.facebook.com/share/p/1AAbrdwv68/?mibextid=wwXIfr

Kosaretsky, S., Mikayilova, U. And Ivanov, I. (2024). Soviet, Global and Local: Inclusion Policies in School Education in Azerbaijan And Russia. Revista Brasileira de Educação Especial, 30, p.e0103. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/384702057_Soviet_Global_and_Local_inclusion_Policies_in_School_education_in_Azerbaijan_and_Russia

Kulczycki, E. (2017). Assessing publications through a bibliometric indicator: The case of comprehensive evaluation of scientific units in Poland. Research Evaluation, 26(1), 41–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvw023

Kuzhabekova, A., & Mukhamejanova, D. (2017). Productive researchers in countries with limited research capacity: Researchers as agents in post-Soviet Kazakhstan. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 8(1), 30-47. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-08-2016-0018

Mamerkhanova, Z., Sakayeva, A., Akhmetkarimova, K., Assakayeva, D., & Bobrova, V. (2025). Development of inclusive education in the Republic of Kazakhstan: An inside view (case of the Karaganda region). Frontiers in Education, 10, 1630225. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2025.1630225

Ruziev, K., & Mamasolieva, M. (2022). Building university research capacity in Uzbekistan. In Building research capacity at universities: Insights from post-soviet countries (pp. 285-303). Cham: Springer International Publishing. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-3-031-12141-8_15