Calling for AI-informed student activism in K-12 schools beyond learnification

The global education landscape is witnessing promising strides in the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into policy frameworks. Across borders, education policymakers, aware of AI’s growing impact on world societies and global economies, are calling for robust, trustworthy measures to understand its digital capabilities more fully. For example, the European Union’s (2024) Artificial Intelligence Act, a regulatory framework, mandates the monitoring of AI systems. The OECD (2025) has made recommendations on generative AI aimed at increasing innovation, fostering international cooperation, and sustaining democracy. The AI Action Summit (2025), hosted in Paris in February 2025, brought together leaders from different countries for AI dialogue on such topics as innovation, trustworthiness, and investment. These and other organizational entities have been underscoring the urgency of grasping AI’s transformative impact on the labor market and international community.

Current education policy and research on AI integration in schools

Education policy and research’s convergence on the frontier of AI integration in schools signals something more than a wave of classroom innovation. At this moment, systemic recalibration is reaching into the infrastructural and legislative foundations of education and across borders. AI implementation demands vision, infrastructure, and, crucially, investment. As nations race to harness AI’s potential in education, major actors have been stepping forward with bold commitments and strategic funding (European Parliamentary, 2024). China’s Ministry of Education (2024) and the White House (2025)—joined by the United Arab Emirates—are presently at the forefront of the global AI-in-schools movement. All such highly influential actors have extended the scope of AI, encompassing primary and middle schools (Amir, 2025).

AI’s role in education is recognized by such countries, with convergence around not just its potential for economic investment but also democratic investment. Perhaps underlying this thinking is the belief that AI should not be limited to a technocratic, efficiency focus geared around political influence and agendas, instead promulgating a depoliticized version of simulated human-like intelligence (Mullen & Eadens, 2026; Sætra, 2020).

We are reminded of Biesta’s (2020) critical appraisal of education as “learnification”—the concern is that this dominant paradigm (learnification) is overly narrow in its focus on learning as individualistic (sidestepping relationships) and learning as a process (omitting content and the purpose of learning).

Scholars are busy examining AI’s transformative potential in education and associated challenges whilst confronting conventional barriers to being educated (Banoğlu et al., 2025; Mullen & Eadens, 2026; Zhong & Zhao, 2025). This line of inquiry supports the use of AI in public education for guiding students’ interests, passions, and strengths in addition to cultivating their own voice, agency, and leadership, in effect transcending schooling’s traditional “grammar” (Tyack &Tobin, 1994).

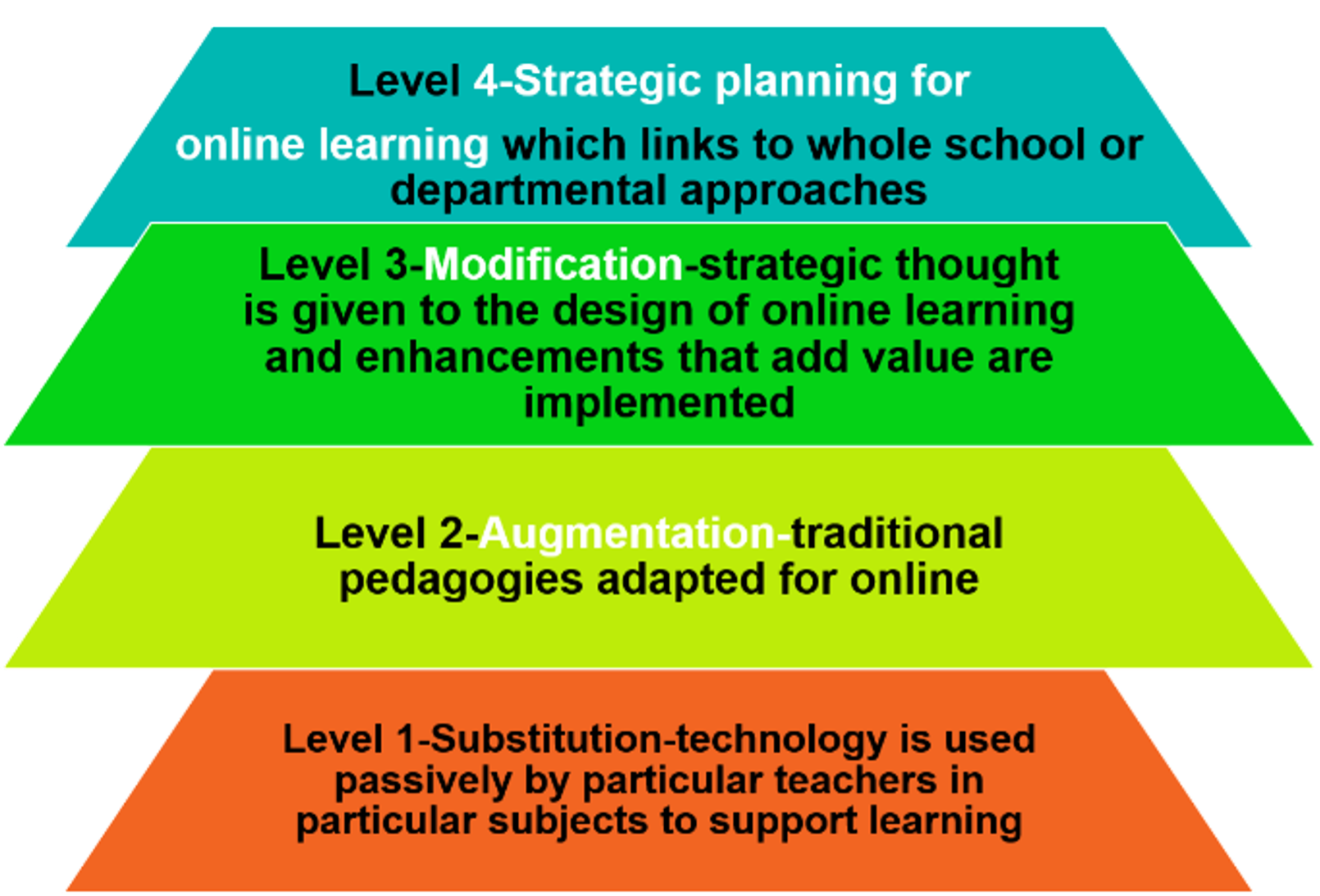

Mishra (2025), an expert in technology integration in teaching, cautioned policymakers that when human “needs” are reduced to technological capabilities, risks ensue. Of great concern is that educational goals could be reshaped around machine capability without accounting for students’ and teachers’ genuine needs. This thinking has also been articulated for digital learning and instruction. On an up note, theory-informed models and actionable strategies that contribute to the evolving discourse on AI ethics are available (see Mullen & Eadens, 2026).

What do student leaders think about AI?

While politics are in motion and policies are being formulated, some areas of academia support these initiatives even though critical perspectives may not be included or attention on the student voice. Banoğlu et al. (2025) critiqued the prevailing narrative that overlooks AI’s untapped potential. This international research team from Hong Kong, Canada, and the US reframed AI as a catalyst for democratic renewal in schools. AI-informed student activism was introduced. Generative AI (which creates text/images using large language models) and agentic AI (which can act on behalf of users) were interrogated for their potential to amplify student voices, protect rights, and support well-being, as well as to tackle problems like cyberbullying.

The research draws upon student experiences, specifically of three former K-12 student leaders—then in their early 20s—from the US, Japan, and Türkiye. Their stories provoke thinking about how AI can be an ally. The student leader from Japan emphasized the role of feedback in democratic processes by enhancing feedback mechanisms within K-12 schools, noting, “If we could use AI-enhanced feedback systems, it would help us improve our system continuously” (p.103). The US student leader suggested that AI could reduce mundane tasks that consume time, explaining, “AI actually removes that friction for you and does boring things most of the time” (p. 102).

Healthy debate around point–counterpoint is necessary when it comes to AI’s role in education and the future. Pasi Sahlberg, faculty at the University of Melbourne, alluded to a growing disconnect from authentic human interaction and relationships due to AI (as cited in Rubin, 2025): “Whereas a lot can be learned through digital media, there is a lot that can’t…. One of those things is the power of human relationships, face-to-face.” Sahlberg warned that systems overly focused on content delivery risk missing the heart of education: “Making first-class humans requires a different understanding of what human interaction can do.”

In this spirit, albeit acknowledging AI’s technical capabilities, two student leaders from Türkiye and the US underscored human interaction’s irreplaceable role in student leadership, to quote: “If you have wise friends or wise family members, I …ask them about a topic that involves leadership ethics [or] that involves emotions” (see Banoğlu et al., 2025, p. 100).

As such, scholars (e.g., Banoğlu et al.,2025; Mullen & Eadens, 2026) suggest the AI’s multifaceted potential and natural limitations enrich student voice, agency, autonomy, and leadership. Priority areas are outlined in research. These include empowering learners to develop more autonomously as leaders, dismantling barriers to information access, emphasizing ethical considerations, and promoting cultural sensitivity.

Key implications of AI-informed student activism are:

Empowering Informed Dialogue: AI can foster student engagement in informed dialogue and meaningful decision-making, enhancing their agency and participation in student-led governance. In some countries, K-12 students are not authorized to organize independently or pursue their own agendas without approval, they often do not know how to establish autonomous organizations without the involvement of adult allies. As voiced by a former student leader: “These are high schoolers who are defending their rights and autonomy, and they lack most knowledge to fully gather the tools to build a student organization or fight against … the administration for their own autonomy” (Banoğlu et al., 2025, p. 103).

AI can help bridge the student activism gap by (a) informing young people about their rights and (b) encouraging them to support and build their own organizations. This engagement could enhance agency and participation in student-led governance structures, potentially leading to more democratic and responsive environments in which younger and older learners alike are capable of leading for impact.

Streamlining Communication: AI can facilitate seamless communication among students, enabling large groups to effectively collaborate on projects. Unlike feedback methods that may favor more vocal or dominant voices, AI can be trained to highlight marginalized and minority perspectives, ensuring that diverse ideas—particularly those advocating for child rights and democratic participation—are both recognized and valued. Feedback can be shared en masse, and AI can distill this information into comprehensible reports that reflect a broad range of peers’ ideas, rather than prioritizing the most common or median views.

This inclusive approach to student leadership and consultation promotes an equitable platform where all students are acknowledged, helping to prevent marginalization of less-heard perspectives. Such comprehensive feedback can assist in discerning next steps in leadership activities, fostering a greater sense of community, collaboration, and ownership of learning.

Bridge-Building: AI’s ability to connect learners cannot be understated. By sharing insights about student leadership initiatives, AI can help to level the playing field. Enhanced knowledge capabilities can empower students to rely less on others, fostering autonomy while reducing the risk of vulnerability to disempowerment and isolation.

This democratizing function of AI is highlighted by a former K-12 school leader: “AI could … provide a legal, equitable way [for] young students who don’t have enough experience … who are trying to initiate an organization or who already are in a student body but don’t like how it’s ruled or their relationship with the school; they can use AI … to [help] compensate [for their] lack of knowledge” (Banoğlu et al., 2025, p. 103).

Cultivating Student Leadership: An expectation is for AI to be grounded in ethical principles and approaches to guide its proper use as well as to monitor misuses. To cultivate student leadership, it is vital that a more complete understanding of AI, together with appropriate uses of applications, inform instruction, apprenticeship, and mentorship.

Further research could put AI’s potential for student leadership to the test, observing its integration with youth leadership to discern the extent to which young people might be empowered with the skills, knowledge, and opportunities to take initiative, make decisions, and enact agency in their communities. From this standpoint, AI would be encompassing various youth activities and programs designed to foster cognitive awareness, leadership skills, civic engagement, and personal development.

Charting a path toward AI-informed student activism

Interest groups influence school knowledge, reducing teachers and students alike to curriculum conduits (Mullen, 2022). Viewing AI as a top-down policy initiative for technology integration in schools circumvents the rich learning shaped by student agency and relationships, echoing previous waves of computerization that have generated millions in technology investments, absent learner voices and input. The AI paradigm poses a significant threat to school and student agency, calling for activism from education stakeholders in schools and higher education.

While optimism about AI’s vast transformative potential is warranted, national politics and policies have been known to fall short of effectively involving school actors and more fully supporting them. By fostering trust and encouraging children’s AI-informed activism, steps can be taken to create a more democratic, equitable, and peaceful world. Empowering students to utilize AI to advocate for their rights, development, and well-being promotes educational equity, globally.

This leads us to say what we envision, which is an AI-informed student leadership “frontline” dedicated to child rights, activism, and democratic participation. Given the tide of AI-driven, profit-oriented ventures in public education systems, creative thinking and resistive efforts are needed. Narrowly focused AI initiatives interfere with or even halt equity in schooling, especially for children from low-income homes or rural communities lacking reliable access to computers, internet connectivity, and/or digital tools, especially in remotely delivered online learning contexts. By prioritizing student voices and learning communities and by integrating AI thoughtfully and ethically into schools, ethical technological advancement can support democratic values and a collective humanity.

Quite possibly, every reader of this blog has an important role to play in shaping the digital landscape in ways that are favorable to the healthy development and leadership of future generations of children and youth.

Key Messages

A global AI-in-schools movement is emerging, collectively portraying AI’s role in education as technocratic and depoliticized, echoing the long-critiqued concept of “learnification.”

An empirical study by Banoğlu et al. (2025) critically challenges this dominant narrative, offering a critical counter-narrative, showcasing AI’s potential to democratize education through insights from K-12 student leaders in the U.S., Japan, and Türkiye.

AI can empower students to amplify their agency, safeguard rights, support well-being, and enhance student leadership, fostering democratic renewal in schools.

AI can enable informed dialogue, streamline communication, and bridge gaps, enhancing collaboration, autonomy, and equity in student-led initiatives.

Encouraging AI-informed student activism can create a more democratic, equitable, and peaceful world, ensuring education aligns with genuine student needs.

Dr Köksal Banoğlu

Education University of Hong Kong

Köksal Banoğlu, Ph.D., is a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the Education University of Hong Kong. His research focuses on the intersection of technology leadership, inferential social network analysis and AI-informed student action, exploring how these interconnections strengthen school leadership, organisational learning and student agency. His recent work has appeared in Educational Management Administration & Leadership, Leadership and Policy in Schools, Leading & Managing, Journal of Professional Capital & Community, School Leadership & Management, Journal of School Leadership, and Professional Development in Education. He is the recipient of the 2025 BELMAS Best Blog Runner-up Award. He serves as Chief Editor of Research in Educational Administration & Leadership, and as Assistant Editor of the International Journal of Leadership in Education. He also sits on the editorial boards of Review of Education, Methodological Innovations, and International Studies in Sociology of Education.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3314-1032

Researchgate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Koeksal-Banoglu

Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/koksalbanoglu

Dr Carol A. Mullen

Virginia Tech, Virginia, USA

Carol A. Mullen, Ph.D., is a Canadian–American Professor of Educational Leadership and Policy Studies at Virginia Tech, Virginia, USA and a Fulbright Senior Scholar alumnus. She is an internationally acclaimed, award-winning mentoring researcher who uses equity/justice and policy lenses. Her research also examines the impact of creativity in different testing cultures through Fulbright-sponsored scholarships to China and Canada, with related study in Australia. Her authored and edited books include Equity in School Mentoring and Induction (2025), Handbook of Social Justice Interventions in Education (2021, edited), and The SAGE Handbook of Mentoring and Coaching in Education (2012, coedited). She is Editor Emerita of the Mentoring & Tutoring journal (Routledge) and past-president of the International Council of Professors of Educational Leadership (ICPEL), Society of Professors of Education, and University Council for Educational Administration (UCEA).

Dr Mullen has received over 30 awards in leadership, research, and mentorship in the social sciences, specifically educational leadership and administration and related fields. These honors include UCEA’s Master Professor Award and Jay D. Scribner Mentoring Award, in addition to ICPEL’s Living Legend Award and the University of Toronto’s Leaders and Legends Excellence Award. She has published 29 books, over 250 journal articles and chapters in others’ books, and 18 guest-edited special issues. Forthcoming is Improving Your College Courses: A Guide for Engaging In Digital Learning, a book coedited with Dr. Daniel Eadens (Myers Education Press). Formerly, she served as school director, associate dean for the college, and department chair at a previous university.

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-4732-338X;

Wikipedia: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Carol_A._Mullen;

Researchgate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Carol-Mullen-2

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Amir, K. A. (2025, May 4). Sheikh Mohammed announces AI as mandatory subject in UAE schools. Gulf News. https://gulfnews.com/uae/government/sheikh-mohammed-announces-ai-as-mandatory-subject-in-uae-schools-1.500115349

AI Action Summit.(2025).https://www.elysee.fr/admin/upload/default/0001/17/786758b38da7b4c16f26dc56e51884b3346684aa.pdf

Banoğlu, K., Patrick, J., & Hacıfazlıoğlu, Ö. (2025). Promises of artificial intelligence (AI) in reframing student agency and democratic participation in K-12 Schools: Perspectives from student leaders. Leading & Managing, 31(1), 90-111.

Biesta, G. (2020). Risking ourselves in education: Qualification, socialization, and subjectification revisited. Educational Theory, 70(1), 89-104. https://doi.org/10.1111/edth.12411

China’s Ministry of Education. (2024, December 2). MOE issues guidance on how to teach AI in primary and middle schools. http://en.moe.gov.cn/news/press_releases/202412/t20241210_1166454.html

European Parliament. (2024). AI investment: EU and global indicators. European Parliament Research Service. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/ATAG/2024/760392/EPRS_ATA(2024)760392_EN.pdf

European Union. (2024). Artificial Intelligence Act. https://artificialintelligenceact.eu/wp-content/uploads/2024/11/Future-of-Life-InstituteAI-Act-overview-30-May-2024.pdf

Mishra, P. (2025, April 23). Who ordered that? On AI, education, and the illusion of necessity. https://punyamishra.com/2025/04/23/who-ordered-that-on-ai-education-and-the-illusion-of-necessity

Mullen, C. A. (2022). Corporate networks’ grip on the public school sector and education policy. In C. H. Tienken & C. A. Mullen (Eds.), The risky business of education policy (pp. 1-22). Routledge.

Mullen, C. A. (2025). Guest editor of special issue, “Creative Responses to Leadership Challenges and Constraints.” Leading &Managing, 31(1). https://journals.flvc.org/leading-and-managing/issue/view/6509/403

Mullen, C. A., & Eadens, D. W. (Eds.). (2026). Improving your college courses: A guide for engaging in digital learning. Myers Education Press.

Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. (2025). OECD Recommendation of the Council on Artificial Intelligence. https://legalinstruments.oecd.org/en/instruments/oecd-legal-0449

Rubin, C. M. (2025,July 4). Are schools ready for the next shutdown? Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/cathyrubin/2025/07/04/are-schools-ready-for-the-next-shutdown

Sætra, H. K. (2020). A shallow defense of a technocracy of artificial intelligence: Examining the political harms of algorithmic governance in the domain of government. Technology in Society, 62, 101283, 1-10. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.techsoc.2020.101283

Schleicher, A., & Mitchell, S. (2025, June 3,). From PISA to AI: How the OECD is measuring what AI can do. OECD. https://oecd.ai/en/wonk/from-pisa-to-ai-how-the-oecd-is-measuring-what-ai-can-do

Tyack, D., & Tobin, W. (1994). The “grammar” of schooling: Why has it been so hard to change? American Educational Research Journal, 31(3), 453-479. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312031003453

White House, The. (2025, April 23). Advancing artificial intelligence education for American youth.https://www.whitehouse.gov/presidential-actions/2025/04/advancing-artificial-intelligence-education-for-american-youth

Zhong, R., & Zhao, Y. (2025). Education paradigm shifts in the age of AI: A spatiotemporal analysis of learning. ECNU Review of Education. https://doi.org/10.1177/2096531125131 5204