We Are the Storytellers: Co-Creating Counternarratives with Black Caribbean Boys

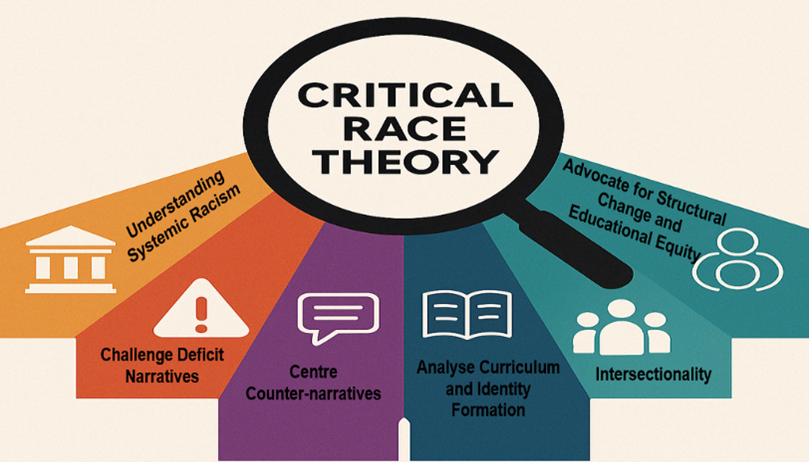

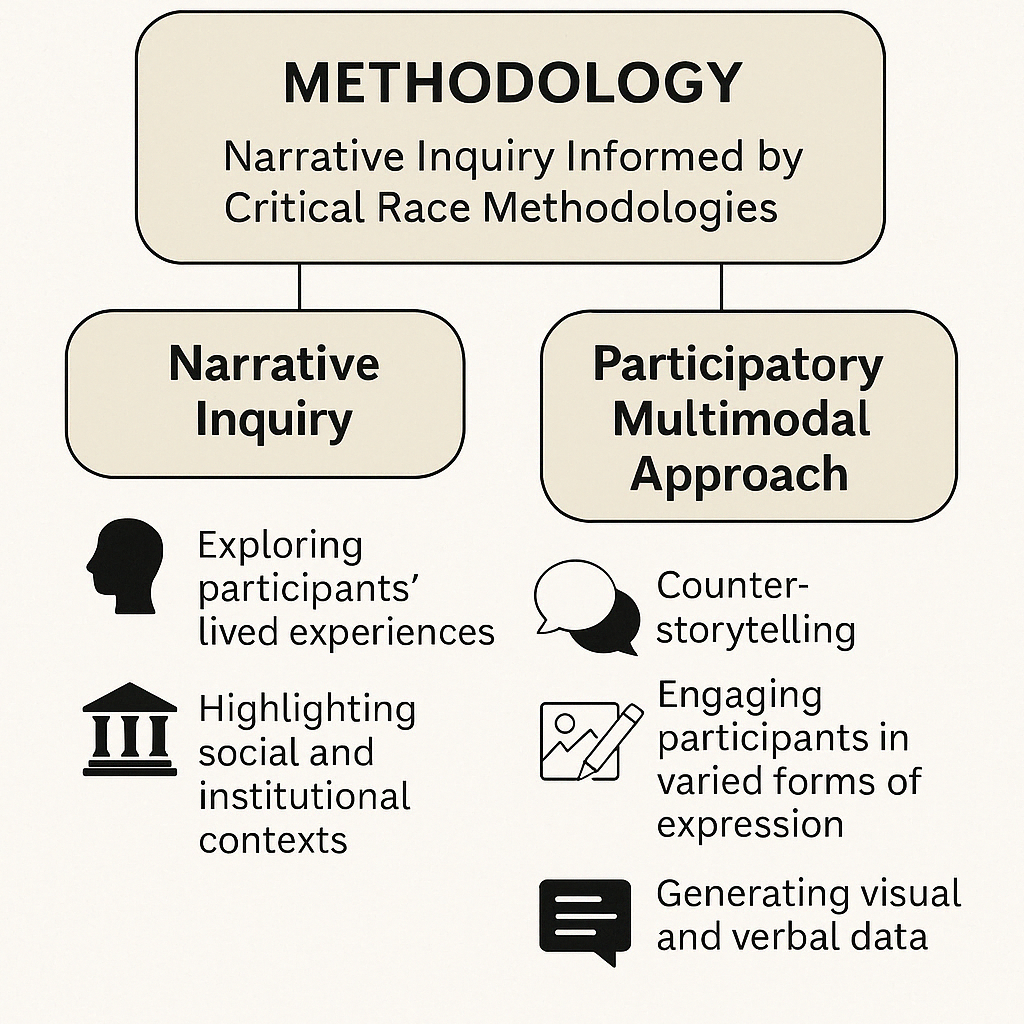

This blog previews the project I will present at ECER 2025, titled ‘Literature as Identity Work: Exploring Self-Discovery Through Texts’. It examines Black Caribbean male students’ experiences with the GCSE English literature curriculum in the UK, positioning literature as a space where identities are negotiated, challenged and reshaped. Through participants’ encounters with canonical texts, the study highlights literature’s dual role as a platform for personal growth, and a mechanism through which cultural exclusion is perpetuated. Rooted in Critical Race Theory (CRT) (Delgado, R. and Stefancic, J., 2023; Gillborn, 2024; Ladson-Billings, 2021) and narrative inquiry (Frank, 2012), the project uses storytelling – both textual and sonic – as a method for disseminating research, amplifying representation and showcasing resistance.

Representation, identity, and the limits of the literature curriculum

Although literature is often hailed as a window or door into other worlds and a mirror reflecting the self (Bishop, 1990), these metaphors take on new significance when curriculum texts fail to reflect the identities, cultures or lived experiences of its readers. For many Black Caribbean male students in England, the GCSE literature curriculum offers few mirrors since the reforms implemented by then Education Secretary, Michael Gove (Institute for Government, 2022; Chandler-Grevatt, 2021) have cemented a syllabus dominated by Eurocentric canonical texts, largely written by White men from the sixteenth to twentieth centuries. Despite their historical and literary value, the stories and contexts frequently fail to reflect the identities, realities and voices of Black Caribbean male students, leaving many to experience the literature curriculum as something to be gazed at from the outside rather than lived from within (Elliott et al., 2021). As one participant observes, “There are other people as good as Shakespeare, with different skin colours but no one knows about them”. Such reflections reveal that, for the participants, literature transcends its status as an academic subject to become an opaque mirror, a battleground and a site for self-definition, resistance and critical identity work.

Heterotopic spaces enable open reflection on race, masculinity and belonging

Viewed through the lenses of CRT and narrative inquiry, the participants’ counter-narratives uncover the personal stakes of curriculum design suggesting that questions of literature and identity are inseparable from questions of method. In this light, my research explores how participants’ engagement with canonical works and selected twentieth- and twenty-first-century texts shapes their navigation of masculinity, race, emotion and belonging.

The study facilitates one-to-one participatory narrative interviews, situated within Foucault’s (1986) conceptualisation of heterotopic spaces — cultural, dialogic environments designed to foster open, identity-affirming reflection. In these spaces, participants are empowered to move beyond the constraints of school-based discussions to critically engage with both the texts and their evolving sense of self.

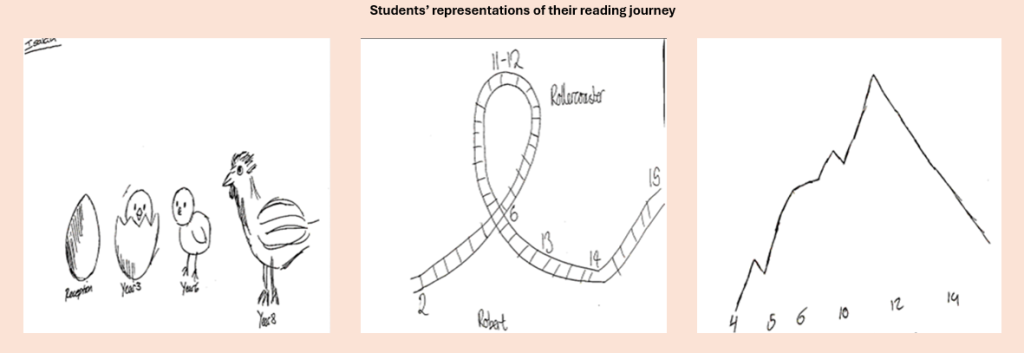

To support emotional processing and deepen participant engagement, I employ a range of multimodal activities including text rating, visual mapping and character reflection (Kress, 2010; Woolhouse, 2017).

One notable strategy involves employing emojis to enable students’ articulation of their emotional responses to texts and characters.

These methodological tools prove effective because they provide a familiar and accessible medium through which to explore affective interpretation.

Sonic dissemination invites audiences to listen and engage with counter-narratives

Most significantly, the power of this study lies in the dissemination of research data. Rather than summarising student responses in researcher-authored prose, narratives are co-created using the boys’ own words as dialogue. Their speech — unpolished, reflective and often emotionally charged — remains intact. This approach allows for narrative framing without distorting the participants’ words, tone or rhythm. Also, by giving sonic life to the participants’ counter-narratives through AI voice simulation, audiences are invited not only to read the data but to listen – to hear counter-narratives in voices that echo their resonance and resistance.

Through this method of dissemination, audiences encounter young Black men speaking on their own terms, articulating nuanced understandings of masculinity, justice, diasporic belonging and the politics of hope (Freire, 2021). Sonic dissemination preserves the emotional texture of participants’ words, enacts the ethics of co-creation (Cohen, Manion and Morrison, 2017), and disrupts normative expectations of data sharing. It also reimagines dissemination as relational listening, a mode that centres empathy, embodiment and presence.

Serving as a commentary to remind us that voice is not only a methodological tool but also a political act — one that challenges the silences imposed by dominant narratives and affirms lived experience as legitimate knowledge — John, a participant, states: ‘I don’t mind people hearing what I said. I just want them to actually listen”. Consequently, my methodological choices do not merely generate data; they open space for new stories to emerge, stories that resonate within academia but also hold the potential to connect with wider audiences through accessible forms of storytelling and voice.

A co-created composite counter-narrative

Unmasking Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde

Students’ counter-narratives explore masculinity, identity and belonging

The composite counternarratives co-created through my research illustrate the students’ reflections on masculinity, identity, justice, racism and diasporic belonging, articulated through their negotiations with literature and wider society. The participants construct masculinity as a fluid, often contested identity, shaped by social context, cultural pressure and lived experience.

While several boys reject emotional vulnerability, critiquing characters such as Romeo (Shakespeare, 1993) as “simpish” and “unstable”, others value traits such as loyalty, self-awareness and quiet strength. Tybalt and Mercutio (Shakespeare, 1993) emerge as models of decisiveness and honour, even when their actions are rooted in violence. By contrast, texts such as Boys Don’t Cry (Blackman, 2024) enable a redefinition of masculinity grounded in emotional growth, caregiving and moral accountability.

Crucially, the students do not engage with masculinity in one uniform way; they actively interrogate what it means to be a man across diverse social and literary contexts (Connell, 1995). Through their counter-storytelling, the boys challenge hegemonic masculine norms (Connell, 1995) which positions certain performances of manhood — particularly those marked by dominance, emotional restraint and heterosexuality as ideal. Their counter-narratives (Solórzano and Yosso, 2002) therefore resist static, deficit-laden constructions of Black masculinity, providing instead complex and situated accounts of identity.

In a system that frequently frames Black Caribbean boys as disengaged or underachieving, this work foregrounds their criticality, emotional intelligence, cultural literacy and capacity for reflective resistance. The participants demonstrate cultural awareness, an understanding of their position in society as well as how they navigate and negotiate its demands. They are not disengaged; they are resisting performance of the self that feels untrue.

At its heart, this project asks educators and researchers to do something very simple but radical: listen. Because when we truly listen to marginalised students, they do more than answer our questions.

They tell us a story.

And sometimes, they rewrite it.

Key Messages

- The GCSE English literature curriculum, shaped by Govian reforms, offers few mirrors for Black Caribbean boys as it prioritises Eurocentric canonical texts.

- The participant’s counter-narratives reveal how literature becomes a site of struggle, identity work, and resistance against deficit views of Black masculinity.

- Using multimodal and narrative methods, the study creates heterotopic spaces for boys to reflect on masculinity, race, belonging and justice.

- Data is disseminated through AI-voiced sonic counter-narratives which preserve emotional texture and extend conventional research outputs by introducing new possibilities for sharing and experiencing participant voices. This approach offers a relational and participatory approach to dissemination.

- The project foregrounds students’ voices as acts of resistance and hope, creating spaces where marginalised young people exercise their agency and transform narrative sites into spaces for reimagining justice, education, identity and belonging.

ECER 2025 –

As part of my ECER 2025 presentation, I will be sharing the composite counter-narrative “We Weren’t Just Reading: Reflection, Resistance, Becoming”, a co-created narrative built from the boys’ direct quotes voiced during interviews. The story explores how literature functions as a critical space for young Black men to reflect on masculinity, identity, representation and belonging whilst developing critical consciousness about the systems that shape their lives.

Through their reflections on texts such as Boys Don’t Cry, Othello, Romeo and Juliet, Macbeth, and An Inspector Calls, the participants interrogate stereotypes, power and exclusion — questioning whose stories are centred and whose are silenced. Their voices challenge dominant narratives of disinterest and underachievement, foregrounding themes that are central to CRT. The composite counter-narrative ‘We Weren’t Just Reading: Reflection, Resistance, Becoming’ reveals that the Black Caribbean male students in my research are not merely analysing literature; they, instead, use it as a tool for self-discovery, resistance and critical reflection to create new understandings of identity, power and belonging.

- Network: 07. Social Justice and Intercultural Education

- Contribution ID: 1195

- Title: Literature as Identity Work: Exploring Self-Discovery Through Texts

- Session Title: 07 SES 02 A: Engaging Families and Alternative Educational Practices

- Date & Time: 09 September 2025, 15:15 – 16:45 (CET)

- Location: Room 001 | Eduka College | Ground Floor

Keisha-Ann Stewart

Edge Hill University

Keisha-Ann Stewart is a PhD researcher at Edge Hill University. Her doctoral research explores Black Caribbean male students’ experiences of literature texts studied at Key Stage 4, examining how these experiences shape their engagement, interpretation and academic responses within English classrooms in England. With a multidisciplinary background in applied linguistics, literature, publishing studies and education, Keisha-Ann’s academic interests include literacy development, anti-racist education, decolonising the curriculum, teacher education, the ethical use of artificial intelligence in education, and the integration of technology to enhance learning and pedagogy. Her work is grounded in a strong commitment to equity, inclusion and culturally responsive teaching.

08 - 09 September 2025 - Emerging Researchers' Conference

09 - 12 September 2025 - European Conference on Educational Research

Since the first ECER in 1992, the conference has grown into one of the largest annual educational research conferences in Europe. In 2025, the EERA family heads to Serbia for ECER and ERC.

In Belgrade, the conference theme is Charting the Way Forward: Education, Research, Potentials and Perspectives

Emerging Researchers' Conference - Belgrade 2025

The Emerging Researchers' Conference (ERC) precedes ECER and is organised by EERA's Emerging Researchers' Group. Emerging researchers are uniquely supported to discuss and debate topical and thought-provoking research projects in relation to the ECER themes, trends and current practices in educational research year after year. The high-quality academic presentations during the ERC are evidence of the significant participation and contributions of emerging researchers to the European educational research community.

By participating in the ERC, emerging researchers have the opportunity to engage with world class educational research and to learn the priorities and developments from notable regional and international researchers and academics. The ERC is purposefully organised to include special activities and workshops that provide emerging researchers varied opportunities for networking, creating global connections and knowledge exchange, sharing the latest groundbreaking insights on topics of their interest. Submissions to the ERC are handed in via the standard submission procedure.

Prepare yourself to be challenged, excited and inspired.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

References

Bishop, R.S. 1990. ‘Mirrors, windows, and sliding glass doors’, Perspectives: Choosing and Using Books for the Classroom, 6(3), pp. ix–xi.

Available at: https://scenicregional.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Mirrors-Windows-and-Sliding-Glass-Doors.pdf (Accessed: 20 August 2025).

Blackman, M. 2024. Boys don’t cry. London: Penguin

Chandler-Grevatt, A. 2021. ‘The wilderness years: An analysis of Gove’s education reforms on teacher assessment literacy’, The Buckingham Journal of Education, 2(2), pp. 149–164.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.5750/tbje.v2i1.1935 (Accessed: 18 August 2025).

Cohen, L., Manion, L. and Morrison, K. 2017. Research methods in education. 8th edn. Abingdon: Routledge.

Connell, R.W. 1995. Masculinities. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Delgado, R. and Stefancic, J. 2023. Critical race theory: An introduction. 4th edn. New York: New York University Press.

Elliott, V., Nelson-Addy, L., Chantiluke, R. and Courtney, M. 2021. Lit in Colour: Diversity in Literature in English Schools. London: Penguin Books UK and The Runnymede Trust.

Available at: https://litincolour.penguin.co.uk/assets/Lit-in-Colour-research-report.pdf (Accessed: 20 August 2025).

Foucault, M. 1986. ‘Of other spaces’, Diacritics, 16(1), pp. 22–27.

Freire, P. 2021. Pedagogy of hope: Reliving pedagogy of the oppressed. Bloomsbury Academic.

Frank, A. 2012. “Practicing Dialogical Narrative Analysis,” in Varieties of Narrative Analysis, pp. 33–52. Available at: https://doi.org/10.4135/9781506335117.n3 (Accessed: 20 August 2025).

Gillborn, D. 2024. White lies: Racism, education and critical race theory. London: Routledge.

Institute for Government. 2022. The Gove reforms a decade on. London: Institute for Government. Available at: https://www.instituteforgovernment.org.uk/sites/default/files/publications/gove-reforms-decade-on.pdf (Accessed: 18 August 2025).

Kress, G. 2010. Multimodality: A social semiotic approach to contemporary communication. London: Routledge.

Ladson-Billings, G. 2021. A scholar’s journey: Critical race theory and education. New York: Teachers College Press.

Shakespeare, W. 1993. The tragedy of Romeo and Juliet. Champaign, Ill.: Project Gutenberg. Available at: http://www.gutenberg.org/etext/1777

(Accessed: August 20, 2025).

Solórzano, D.G. and Yosso, T.J. 2002. ‘Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research’, Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), pp. 23–44.

Available at: https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/107780040200800103 (Accessed: 20 August 2025).

Stewart, K. 2025. Beyond the page: Literature as a catalyst for identity and resistance. Edge Hill University. Poster.

Available at: https://doi.org/10.25416/edgehill.29616704.v1.

Woolhouse, C. 2017. ‘Multimodal life history narrative: Embodied identity, discursive transitions and uncomfortable silences’, Narrative Inquiry, 27(1), pp. 109–131.

Available at: https://research.edgehill.ac.uk/en/publications/multimodal-life-history-narrative-embodied-identity-discursive-tr (Accessed: 20 August 2025).