Using nonviolence to reconceptualize inclusive education in the Global South

My doctoral research has been exploring how developing a philosophy of nonviolence can help offset discrimination and exclusion in Chile, a country that has attempted to tackle the issue of inclusiveness through a Global North narrative that has focused primarily on disability and special needs. This blog post explores how nonviolence education can promote a sense of equality and inclusion not purely from such perspective, as has been the norm for the last two decades, but from one anchored in an understanding of cultural, economic, sexual, and ethnic diversity.

Previous assumptions on inclusivity

The very nature of my research project has inclusiveness at its core; not exclusively as a method often and primarily focused on students with special needs, but as a way to experience human relations rooted in an equitable view of others. It involved reading and discussing nonviolent perspectives in education, engaging in weekly contemplative practices such as developing empathy and practicing compassion, and peer-teaching. Participants were all pre-service teachers from Chile, a nation that in the last 4 years has been beset by social violence, much of which spilled over into educational establishments.

These participants’ previous assumptions on what inclusiveness is ranged from “I thought inclusiveness was only a way to adapt materials for special-needs students”, to “I used to think about inclusiveness from a technical perspective rather than understanding what makes a person different from another, or singular”, to “I used to believe inclusiveness was about including other people, but now I understand it as being aware of their differences, acknowledging and appreciating them”

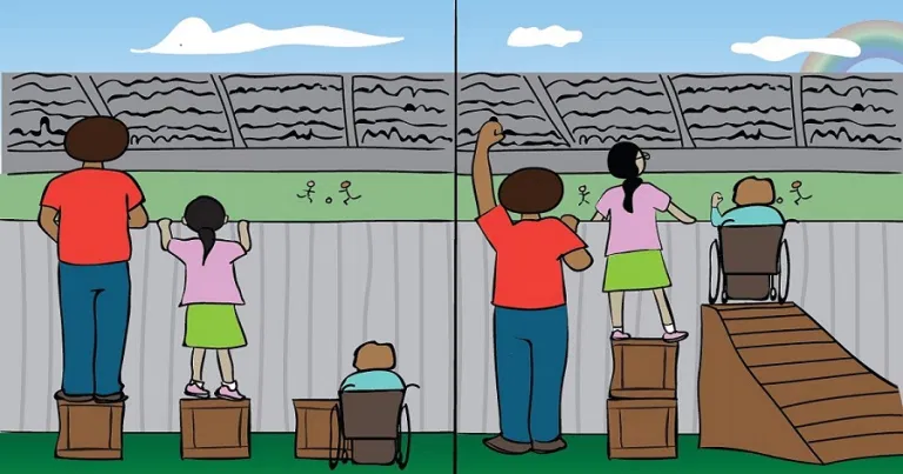

This somewhat incomplete understanding of inclusiveness is hardly surprising, if one is to look at two factors. The first is the definitions and principles of inclusive education we find in research done by Chilean scholars and Chilean government documents; for while it is true that Law 20.845 on Inclusive Education from 2016 seeks the “elimination of discrimination and the approach to diversity”[1], it is also acknowledged that these efforts have focused on and been prompted by widening access primarily to people with disabilities. A report from the National Disability Agency states that inclusive education has been “driven towards the social participation of people with disabilities, their families and civil society, in order to implement the changes demanded by students and our society” (p.1). Research by Chilean scholars in this area (Iturra-Gonzalez, 2019; Manghi et al., 2020; Martinez and Rosas, 2022) on the other hand, tends to use the terms “inclusive education” and “education for students with special needs” interchangeably. There is, as I mentioned, a second factor that shapes this view of inclusiveness: a close inspection of available research done in Chilean education reveals that it draws heavily and almost exclusively on studies and sources from the Global North on this issue, and this is problematic: such research has in fact for decades focused almost exclusively on disability rather than on a holistic approach.

[1] In Spanish in the original: “eliminación de la discriminación y el abordaje de la diversidad”, translation by me.

An argument for what inclusive education should mean today

Given the above, I argue that the idea of inclusiveness I have described is both inaccurate and incomplete, and it is here that nonviolence educational philosophy brings a more holistic understanding of what inclusiveness should look like. To begin with, Judith Butler (2020) has argued that all lives have equal worth; violence in any dimension arises when we see others’ lives as having less worth. Inclusiveness from a nonviolent perspective comprises everyone who has been historically marginalized, excluded, and discriminated against. In other words, whose lives have been socially and culturally devalued. This is where we can establish a link to non-Western traditions (i.e., Ubuntu, BuenVivir, Buddhism, and yoga), which were explored during the study. What these traditions have in common is that they promote a sense of a mutually bound existence regardless of our faith, gender, ethnicity, beliefs, modes of life, ability, literacy or education.

When defining ubuntu, for instance, Desmond Tutu (1999) explains:

“A person with ubuntu is open and available to others, affirming of others, does not feel threatened that others are able and good, for he or she has a proper self-assurance that comes from knowing that he or she belongs in a greater whole and is diminished when others are humiliated or diminished, when others are tortured or oppressed, or treated as if they were less than who they are” (p.29)

He further adds that the ultimate goal of ubuntu is to achieve social harmony through shared human participation, and that in the end, we can only be human beings through other human beings; therefore, committing an act of violence against someone is an action of dehumanizing both the victim and ourselves.

These were concepts that were missing from the participants’ original interpretation of inclusiveness, and why they were exposed to these ideas early on in the project; for instance, one of the earliest assignments for participants was to watch a short video on the meaning of inclusiveness in education by Indian scholar Sadhguru. His vision, which I share, is that inclusiveness is not “an idea or a campaign”, but an individual experience of connecting to other human beings, and of bringing this connection into the whole range of activities we engage in, be it educational, economic or spiritual, in order to flourish. One participant explains:

“I really liked what Sadhguru mentioned in his speech about inclusiveness in education, “Survival cannot happen without inclusiveness”, as I think this is a point that many people tend to forget. For me, inclusiveness is about integrating different people into a group. However, this integration should not only be to include or accept a person into this group, this action also serves to see other people as equals” – P24

Perhaps the most important insight participants expressed concerned a paradigmatic shift that moved from an individualistic mindset to a more collective one, as can be seen from the observations below:

“I noticed the sense of community in which I work with others as “we”, but also as my own growth as an individual. Western people, on the other hand, are taught that the only thing that matters is the “ego”, ourselves, everything that surrounds us, we own it” – P1

“I am part of a network that should be constructed with love, understanding, and diversity. We are part of the same whole in humankind, but we are diverse. It is this diversity that configures this classroom. I am because you are: I wouldn’t be a teacher without the students and vice-versa”– P10

“In Indigenous knowledge, we are devoted to help others not for the sake of our own benefit but, more profound, for the sake of our humanity” – P20

“It is the relationship with others that makes us human. The interactions with people that surround us is what allows to be fulfilled, we thrive in communities but we also see our humanity when we come in contact with those towards whom we direct it” – P2

These insights speak of several dimensions worth highlighting; the first is the impact of Western epistemologies in creating an individual viewed as separate from other human beings, and which directly contradicts what an inclusive environment should be. Secondly, they emphasize the fact that human beings are in fact interdependent and not the participants of what Butler calls ‘the fantasy of our self-sufficiency’ (2020). They also speak of the realization of what non-Western wisdom traditions offer in this context: a philosophy that proposes a manner in which we as humankind should be living: not for ourselves but for each other. As this participant notes:

“Fostering this idea that we depend on our peers to learn is a big step in starting to create a non-violent environment. Stop competing, include those who have different ideas, want the success of my classmates for the good of everyone. These are ideas that the new generations will acquire and gradually reform the worldview of society”. – P5

Conclusion

In conclusion, what participants’ insights show is how the nonviolent perspectives offered throughout the project indeed helped them reconceptualize their conception of inclusiveness to one that encompasses the full diversity of our human experience, rather than a method focused on disability alone as an exclusionary/inclusionary dimension. Several of the realizations and comments offered here speak of an appreciation of individual differences, while at the same time embracing inclusiveness as a guiding moral value that recognizes our shared humanity.

I would also argue that this kind of inclusiveness constitutes the strongest form of opposition against any kind of Othering, and that to cultivate that, to generate the kind of love that Garvey (1923) suggested should infuse education so that it could ‘soften the ills of the world’ (p.17), we need to learn to see others not as Others but through an empathetic lens that rehumanizes everyone regardless of our differences. This in the end is the contribution that non-Western epistemologies can make in the formulation of a nonviolent pedagogical framework.

Key Messages

- We need to review how we view ‘inclusion’ from primarily focusing on students with special needs

- Inclusion must be anchored in an understanding of cultural, economic, sexual, and ethnic diversity

- Non-violent education can promote such a sense of equality and inclusion

- It is important to decolonial perspectives on inclusiveness

Gaston Bacquet

Associate Tutor / 3rd-year PhD student

Gaston Bacquet is a 3rd-year PhD student at the University of Glasgow. His research attempts to bring decolonial perspectives on nonviolence to teacher training within the Global South; said research draws from indigenous wisdom traditions such as ubuntu and Buen Vivir, as well as Eastern philosophy, and it aims at using the philosophy of nonviolence as a means to promote inclusiveness in all its dimensions. He also works as an associate tutor at Glasgow, where he teaches Qualitative Research Methods, Modern Educational Thought and supervises postgraduate students in the Educational Studies and TESOL programs. He is a guest lecturer for Education and Violence in the Education and Sustainable Development Master’s Program.

Research Gate link: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Gaston-Bacquet-2

ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000-0002-9802-7249

Staff profile: https://www.gla.ac.uk/schools/education/staff/gastonbacquet/

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Brito-Rodriguez, S., Basualto-Porra, L., Posada-Lecompte, M. (2021). Perceptions of Gender Violence, Discrimination, and Exclusion among University Students. Revista Interdisciplinaria de Estudios de Genero de El Colegio de Mexico. Retrieved here: https://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?pid=S2395-91852020000100209&script=sci_arttext

Butler, J. (2020). The Force of Nonviolence: An Ethico-Political Bind. Verso https://www.versobooks.com/books/3758-the-force-of-nonviolence

Garvey, M. (1923) In Amy Jacques-Garvey (Ed.) Philosophy and Opinions of Marcus Garvey, vol. 1.Atheneum.

Iturra Gonzalez, P. (2019). Dilemas de la educación inclusiva de Chile actual. Revista Educacion Las Americas8, 1-13. https://revistas.udla.cl/index.php/rea/article/view/7/6

Manghi, .D., Bustos Ibarra, A., Conejeros Solar, M.Aranda Godoy, I., Vega Cordova, V., Diaz Soto, K. (2020). Comprender la educación inclusiva chilena: Panorama de políticas e investigación educativa. Cadernos de Pesquisas 50(175), 114-134. https://www.scielo.br/j/cp/a/YsJW7Td5j8KkPxwrqHYTmrq/?lang=en

Martinez, C. & Rosas, R. (2022). Students with special educational needs and educational inclusion in Chile: Progress and challenges. Revista MedicaClinica Las Condes 33(5), 512 – 519. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0716864022001031

Rojas, M.T., Astudillo, P. and Catalan, M. (2020). Report: Diversidad y Educacion Sexual en Chile: Identidad sexual (LGBT+) e inclusion escolar en Chile. UNICEF. Retrieved at: https://www.mineduc.cl/wp-content/uploads/sites/19/2022/03/DIVERSIDADSEXUALYEDUCACION_CHILE.pdf

Ryoo, J,, Crawford, J.,Moreno, D. & McClaren, P. (2009), Critical Spiritual Pedagogy: Reclaiming Humanity through a Pedagogy of Integrity, Community, and Love, Power and Education 1(1), 132-148

Tutu, D. (1999). No Future Without Forgiveness. Image Books

DE INCLUSIÓN ESCOLAR QUE REGULA LA ADMISIÓN DE LOS Y LAS ESTUDIANTES, ELIMINA EL FINANCIAMIENTO COMPARTIDO Y PROHÍBE EL LUCRO EN ESTABLECIMIENTOS EDUCACIONALES QUE RECIBEN APORTES DEL ESTADO https://www.bcn.cl/leychile/navegar?idNorma=1078172.