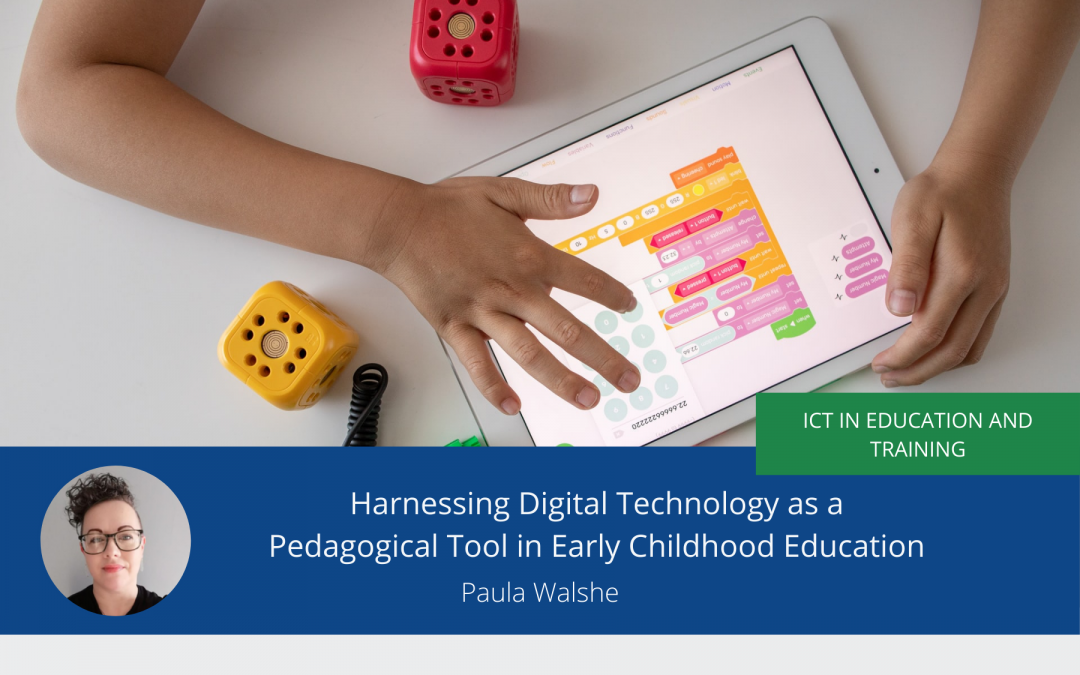

Harnessing Digital Technology as a Pedagogical Tool in Early Childhood Education

Children today are born into a world where digital technology is omnipresent and permeates all areas of their lives (O’Neill, 2018). Yet one area which appears hesitant to embrace technology and harness the possibilities it can provide is the early childhood education sector (ECEC).

Here in Ireland, the Department of Education and Skills (DES) has developed a digital strategy for primary and post-primary schools. This is fortified by a national support service which provides training and resources to support teachers in successfully incorporating technology in their educational practice. However, the DES has stopped short of recommendations for technology to enhance learning for children in ECEC and has instead recommended further research in this area (DES, 2020).

Internationally, the European Commission has stated that 26 out of 38 countries included in their 2019 report are incorporating technology within their ECEC educational guidelines. Ireland is not included in that list of 26 (European Commission, 2019).

From passive to active use of technology

Photo by Jelleke Vanooteghem on Unsplash

Current research has found that young children are already proficient in digital technology use by the age of 3 years old (Marsh et al, 2015). In addition, further research findings from the Growing up in Ireland longitudinal study report that technology is the most favoured form of play for 9-year-old children, more popular than reading a book or even playing with their friends (ESRI, 2021).

When considering technology, devices such as smartphones and tablets initially come to mind, but what if the foundations were laid at the ECEC stage for thinking about technology as much more than streaming animations, social media, and games? An opportunity exists here for the introduction of technology as a developmentally appropriate pedagogical tool for ECEC children, many of whom are already technologically proficient, to open up the possibilities of technology for more than the aforementioned passive activities. This knowledge could inform and expand children’s engagement with technology right through their educational lives.

Examples of active uses of technology

Photo by Eduardo Barrios on Unsplash

From an accessibility perspective, it is important to acknowledge that ECEC settings may have varying degrees of access to technology. For example, access may be limited by resources, practitioner training, or funding, however, there are ways to incorporate technology which are both affordable and accessible and do not require a large investment.

Some simple methods for active uses of technology with ECEC children might include:

- Examining bugs under a digital microscope.

- Simple robotic sets.

- Reflecting with children using photographs, video, and audio clips of them and their play.

- Engaging with another setting as online “pen pals” via email or even video conferencing.

- Invite parents who have an interesting job or story to tell into the setting via video conference.

- Microphones for children to interview each other and listen back together.

- Use an online tool such as Google Drawings to collaborate on artwork with family or with another setting.

- Silent videos for children to narrate and act out.

- Email and pictures from home – favourite food, my room, my favourite toy.

- Search for recipes and order ingredients online, then cook together.

The future of technology in ECEC

Photo by Giu Vicente on Unsplash

But why stop there! Imagine the possibilities of the future and how they could have been so useful for children during the COVID-19 pandemic. For example, so many children missed out on their final year in ECEC and the associated social and emotional preparation for their transition to primary education that would have been provided.

What if augmented or virtual reality technology had been mainstream and accessible during that time. Children could have engaged in a virtual walkthrough of their new primary school environment and had a meet and greet with their primary school teacher and even classmates. This may sound like a somewhat futuristic idea for ECEC, but who would have imagined 30 years ago the technologies which exist today? Such technologies may be expensive now, but like all new technology, surely they will become more affordable over time.

Moving forward, a 2021 report on the uses of technology in ECEC, both pre- and post-pandemic, has highlighted the need for policies and procedures to be developed to provide appropriate guidance for increased utilisation of technology within ECEC pedagogical practice (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 2021). This is reflective of the current lack of direction on technology within the ECEC curriculum in Ireland’s Aistear curriculum and Síolta quality frameworks. Although notably, the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) are currently engaged in a project to update the Aistear curriculum framework which will hopefully address this gap in an Irish context. The OECD (2021) has also recommended the provision of practitioner training and the development of age-appropriate tools to further support the effective incorporation of technology in ECEC pedagogical practice. Of course, there are practical concerns that must be considered, such as ensuring that a balance is struck between engaging with technology for pedagogical use and avoiding an excess of screen time, as suggested by Finnish pedagogues (OECD, 2021). Additionally, we must ensure that the ECEC curriculum does not become dependent on technology so that those who do not have equitable access to technological tools are not disadvantaged. However, such issues further underpin the importance of developing and providing relevant training for ECEC professionals, appropriately embedding technology within the curriculum and quality frameworks, and considering the possibilities of technology in broader terms beyond merely smartphones, tablets, search engines, and streaming apps.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Paula Walshe

ECEC Trainer and FET Assessor

Paula Walshe is an ECEC trainer and placement assessor in the further education and training sector and a freelance writer. She currently holds a BA (Hons) in Early Childhood Education and will complete her studies for a Master’s Degree in Leadership for ECEC in 2022. Paula has extensive ECEC experience in both pedagogical practice and ECEC management. You can learn more about Paula’s work at her website (www.thedigitalearlychildhoodeducator.ie), where she writes a weekly blog on current topics in Early Childhood Education and Care in Ireland and provides useful professional and academic resources for students and professionals in this sector.

LinkedIn: Paula Walshe

Twitter: @digitalearlyed

Instagram: @digitalearlychildhoodeducator

Paula and an ECEC colleague have also established a Twitter page @ECEQualityIrl – a community of professionals sharing ideas and knowledge on all things quality, pedagogy, and professional practice in ECEC in Ireland.

References and Further Reading

Department of Education and Skills. (2019). Digital Learning Framework for Primary Schools. Dublin: Stationery Office. https://www.dlplanning.ie

DES. (2017). Síolta the National Quality Framework for Early Childhood Education. Dublin: Early Years Education and Policy Unit. https://siolta.ie/manuals.php

DES. (2020). Digital Learning 2020: Reporting on practice in Early Learning and Care, Primary and Post-Primary Contexts. Dublin: Stationery Office. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/c0053-digital-learning-2020-reporting-on-practice-in-early-learning-and-care-primary-and-post-primary-contexts/

ESRI. (2021). Growing Up in Ireland, National Longitudinal Study of Children: The lives of 9 year olds of cohort ‘08. Dublin: ESRI. https://www.esri.ie/publications/growing-up-in-ireland-the-lives-of-9-year-olds-of-cohort-08

European Commission. (2019). Key Data on Early Childhood Education and Care in Europe – Eurydice Report 2019. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union. https://eacea.ec.europa.eu/national-policies/eurydice/content/key-data-early-childhood-education-and-care-europe-–-2019-edition_en

Marsh, J. 2014. The Relationship Between Online and Offline Play: Friendship and Exclusion. In Children’s Games in the New Media Age, edited by A. Burn and C. Richards, 109–134. London: Ashgate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/303572020_The_relationship_between_online_and_offline_play_friendship_and_exclusion

National Council for Curriculum Assessment. (2009). Aistear: the Early Childhood Curriculum Framework. Dublin: NCCA. https://ncca.ie/media/4151/aistear_theearlychildhoodcurriculumframework.pdf

O’Neill, S. (2018). Technology Use in Early Learning and Care: A Practice Dilemma. ChildLinks: Children and the Digital World, Barnardo’s, Issue 3, 2018. https://shop.barnardos.ie/products/ebook-childlinks-children-and-the-digital-world-issue-3-2018

OECD. (2021). Using Digital Technologies for Early Education during COVID-19: OECD report for the G20 2020 Education Working Group. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/using-digital-technologies-for-early-education-during-covid-19_fe8d68ad-en