5 practical tips for maths teachers for the design of emotion-sensitive classrooms

“If I fill in this survey, will all mathematics classes be removed?”

That was one of the questions the participants asked most often when I was collecting my PhD data, aiming to examine middle school students’ academic emotions in mathematics classes. Many of the students completed the surveys in the hope that they would be excused from all future mathematics classes. The sad truth was that this sentence was a kind of reflection of those students’ feelings.

As described by Rosenberg (1998), emotions are “acute, intense, and typically brief psychophysiological changes that result from a response to a meaningful situation in one’s environment” (p. 250). Students experience such intense feelings during each phase of their academic lives in education, which foregrounds educators’ and researchers’ attention to work on this topical phenomenon. My study findings have motivated my continued interest in researching in this era to determine why students’ emotions matter at schools and what could be done to design emotion-sensitive classrooms.

Academic emotions are important, but why?

Imagine a fourteen-year-old child is taking a mathematics test on algebraic equations. Unfortunately, the questions are not easy, and the child cannot remember the formula. On the other hand, the child recognizes his parents’ expectations about the test, and time is passing. The heart and sweating rate of the child might increase; he might wish to have escaped from taking the test; the test might induce him to experience high stress, and all of these might reflect on his face. In short, the child is experiencing test anxiety.

As described in the given situations, emotion is a complex construct, including affective, cognitive, motivational, expressive, and physiological dimensions (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun & Linnenbrink-Garcia, 2012, 2014). Based on Pekrun’s (2006) control-value theory of achievement emotions, students might experience various emotions due to achievement activities and achievement outcomes. These emotional experiences of students might exert an influence on their cognitive resources, motivation to learn, learning strategy use, and self-regulated learning, which have a place on their learning and achievement. The most crucial thing is that each element is reciprocally related, so the association between emotions, motivation, and learning-related variables would be dynamic. That foregrounds attention to why both educators and researchers should seek and construe students’ academic emotions.

Mathematics, in particular, has consequential effects on students’ emotions regarding the nature of the discipline, teaching quality, pedagogical knowledge and skills of mathematics teachers, and various student-related factors. Because of the rising focus on 21st-century skills and the “frightening” reputation of math classes, distinct student emotions may stem from their learning activities and outcomes in this discipline. Therefore, my research route specifically addressed students’ achievement emotions in mathematics.

A short glance at students’ mathematics academic emotions in Turkey

My research addressed the antecedents and consequences of the emotional experiences of middle school students (10-14 years of age) in mathematics. In Turkey, where the context of the study was built, mathematics is an often feared subject domain with an increased level of education (Çalık, 2014). Students often fall behind on mathematics competencies regarding Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) results (OECD, 2010, 2013, 2016, 2019).

In addition, students’ capability judgments towards accomplishing mathematics tasks were below, and their anxiety was above the OECD average (Education Reform Inıtiative, 2013). Those results might signify the changes in intensity and the variety of the experienced emotions in this subject domain across grade levels. As just a small part of my research, the findings indicated that 8th-grade students (13-14 years of age) tended to experience less enjoyment and more anxiety and anger than 7th-graders, which raises the first question of why such a decline occurs. Indeed, a number of student-related, teacher-related, parent-related, instruction-related, and assessment-related factors for this trend (Çalık, 2021) bring the second question to our minds: What could be done in designing emotion-sensitive classrooms?

5 practical tips for maths teachers for the design of emotion-sensitive classrooms

Here are several suggestions for designing emotion-sensitive classrooms regarding the potential sources and consequences of academic emotions based on the control-value theory of achievement emotions (Pekrun, 2006). These five tips might be beneficial for mathematics educators to improve the teaching quality of their classes. Those would also lend themselves to regulating students’ emotional experiences in mathematics.

Make a connection between the subject matter and real-life

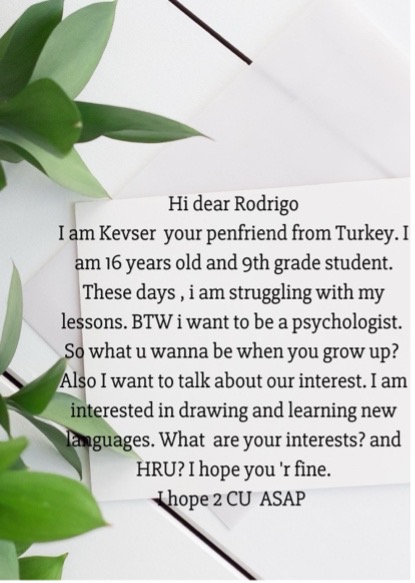

As one of the basic process standards of NCTM (National Council of Teachers of Mathematics), students should be able to recognize and apply mathematics in contexts outside of mathematics, which requires the connection between subject matter in mathematics and real life. When maths teachers design authentic learning environments, students in those contexts could easily identify where they might apply the knowledge and skills they have learned in mathematics classes.

In particular, problem-based and project-based learning approaches might be adopted while creating lesson plans. In those cases, students would have the opportunity to learn, apply, and assess the knowledge by dealing with real-life problems, such as teaching how to calculate means or draw bar graphs through a given real-life scenario. Such practices promote the value of learning math and improve learning motivation for mathematics.

Plan the lesson around the student-centered learning activities to contribute to students critical and creative thinking, problem-solving, research, and communications skills

In line with the connection of mathematics with real life, planning mathematics classes around student-centered learning activities would ease students’ understanding of mathematics concepts. Accordingly, constructive learning practices, including problem-based and project-based learning approaches and cooperative learning strategies, would make students active in learning processes and hold them responsible for their learning.

During the teaching process, employing learning technologies, including Web 2.0 tools (e.g., concept mapping tools, assessment tools, interactive presentations, animation and video, Word clouds), dynamic geometry software, and statistical packages, make mathematics learning more enjoyable for students. Those tools captivate learners’ attention by cultivating inquiry, critical and creative thinking skills, and collaboration among learners. Besides, students have the opportunity to express themselves in more than one suggested way and receive immediate feedback from their teachers and peers in mathematics. That might also increase their engagement, motivation to learn, and positive emotions.

Give individual, prompt, and constructive feedback to students

Mathematics teachers may provide process feedback that reveals detailed information about students’ progress on what is expected of them and what they should do to achieve the intended knowledge and skills in mathematics. For instance, rather than comparing the student with his/her peers or telling the child, “Ok! You’re correct!,” for a typical mathematics problem, the mathematics teachers might come up with a statement, such as “I noticed that you came up with an original solution for this problem which you have not tried before, just amazing!”

In other words, teachers might individualize their feedback by highlighting the strengths and weaknesses of the child by relating their previous projects, homework, assignments, performances, etc. However, the weaknesses might be considered “yet to be accomplished sides” rather than deficits. Otherwise, students are more likely to attribute their failure and achievement in mathematics to unstable and uncontrollable situations, which might boost the rate of experiencing negative emotions. In short, individual and constructive process-oriented feedback foregrounds attention on the efforts put in by students, which also contribute to the level of interest in mathematics.

Make students feel successful by adding their mastery experiences

Self-efficacy is one of the strongest allies of positive emotions. In mathematics, students with high self-efficacy experience more positive and less negative emotions, so adding up self-efficacy beliefs might trigger students’ positive emotions in mathematics. Particularly, helping students reach success in mathematics adds to their mastery experiences in this field.

For this aim, mathematics teachers might divide the tasks into smaller chunks and make students form reasonable goals upon completing those chunks rather than at once. For instance, by giving short homework at first, then increasing the intensity and the number, or asking students to write math dairies or journals to see what they have accomplished and learned each day. Each student can learn at their own pace; however, completion of smaller steps would make students experience success and feel more capable, which, in return, would make them more optimistic and less of a ‘math hater’.

Display high enthusiasm for teaching and be sincere while communicating with students

As a last tip to design emotion-sensitive classrooms, teacher emotions are of value. Teaching is an emotion-laden job, so teacher enthusiasm is a key element for designing supportive teaching and learning environments. As well as enthusiasm and motivation, negative emotions, such as anxiety, anger, and boredom, would also be mirrored by students. Students are more likely to integrate the feelings experienced by teachers and experience similar feelings.

Therefore, the experience of high enthusiasm for teaching influences not only teachers but also students in the long term. In order to increase teaching enthusiasm and positive teacher emotions in mathematics, the bond between students and teachers should be so strong that both parties (teacher and student) would enjoy the teaching and learning process. That would be provided by ensuring sincerity during communicating with students. For example, mathematics teachers who make eye contact while talking with students, call students by their names, use humor while teaching math, mind their tone of voice, and are mindful of their body language. Those tips will not only support communication between students and teachers but also reduce the likelihood of experiencing negative emotions.

Key Messages

- Teachers should design authentic learning environments in which students are provided with learning opportunities to apply their knowledge and skills in different disciplines and real life.

- The mathematics lessons should be designed around student-centered learning activities that cultivate the 21st-century skills of students.

- The feedback given to students should be individual, prompt, and constructive.

- The increase in mastery experiences could make students feel successful and foster students’ self-efficacy beliefs so they may experience more positive emotions.

- Teaching enthusiasm is also critical for students’ emotions, so the student-teacher interaction is of value.

Dr. Başak Çalık

Assistant Professor in the Educational Sciences Department of Istanbul Medeniyet University, Turkey & Postdoctoral Research Scholar in the Educational Psychology Department of City University of New York, Graduate Center, US

Dr. Başak Çalık is an Assistant Professor in the Educational Sciences Department of Istanbul Medeniyet University, Turkey & Postdoctoral Research Scholar in the Educational Psychology Department of City University of New York, Graduate Center, US. She holds a doctorate in Curriculum and Instruction from Middle East Technical University, Ankara, Turkey.

Her doctoral dissertation was supported by the Turkish National Science Foundation International Research Fellowship Program and the Middle East Technical University Academic Research Projects Grant. The dissertation study entitled “Investigation Of Middle School Mathematics Teacher Emotions And Their Students’ Mathematics Achievement Emotions: A Mixed-Methods Study” received the METU Outstanding Dissertation Award. Dr. Çalık received the Turkish National Science Foundation International Postdoctoral Research Fellowship to continue her studies at the City University of New York, Graduate Center. Her research interests include affective aspects in the teaching and learning process, academic emotions of teachers and students, self-efficacy, and teaching quality.

Profile in Researchgate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Basak-Calik

Profile in Linkedin: https://www.linkedin.com/in/ba%C5%9Fak-%C3%A7al%C4%B1k-57a23687/

University Profile: https://avesis.medeniyet.edu.tr/basak.calik

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Çalık, B. (2014). The relationship between mathematics achievement emotions, mathematics self-efficacy, and self-regulated learning strategies among middle school students. (Unpublished Master Thesis). Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

Çalık, B. (2021). Investigation of middle school mathematics teacher emotions and their students’ mathematics achievement emotions: a mixed-methods study. (Unpublished Doctoral Dissertation). Middle East Technical University, Ankara.

Education Reform Initiative (2013). Türkiye PISA 2012 analizi:Matematikte öğrenci motivasyonu, özyeterlik kaygı ve başarısızlık algısı [Turkey PISA 2012 analysis: Student motivation, self-efficacy, anxiety and failure perception]. Retrieved from http://erg.sabanciuniv.edu/sites/erg.sabanciuniv.edu.

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2010). PISA 2009 results: What students know and can do – Student Performance in reading, mathematics and science (Volume I). Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisaproducts/48852548.pdf 289

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2013). PISA 2012 results in focus: What 15-year-olds know and what they can do with what they know. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/keyfindings/pisa-2012-results-overview.pdf

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2016). PISA 2015 results in focus. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/pisa-2015-results-in-focus.pdf

Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) (2019). PISA 2019: Insights and interpretations. Retrieved from https://www.oecd.org/pisa/PISA%202018%20Insights%20and%20Interpretations%20FINAL%20PDF.pdf

Pekrun, R. (2006). The control-value theory of achievement emotions: Assumptions, corollaries, and implications for educational research and practice. Educational Psychology Review, 18, 315–341. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9

Pekrun, R., & Linnenbrink-Garcia, L. (2012). Academic emotions and student engagement. In S.L. Christenson et al. (eds.), Handbook of research on student engagement (pp. 259-282). Springer.

Pekrun, R. & Linnenbrick-Garcia, L. (2014). Introduction to emotions in education.

In R. Pekrun & L. Linnenbrick-Garcia (Eds), International handbook of emotions in education (pp. 1-109). New York and London: Routledge.

Rosenberg, E. L. (1998). Levels of analysis and the organization of affect. Review of

General Psychology, 2, 247–270. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/1089-2680.2.3.247