The perceptions of minoritized pupils on student-teacher relationships

At ECER 2023 in Glasgow, Julia Steenwegen from the University of Antwerp will present her research about the minoritized students, and their perceptions of the student-teacher relationships in mainstream and supplementary schools. We asked Julia to give us an overview of her research, and the implications for minoritzed students in Belgium, and beyond.

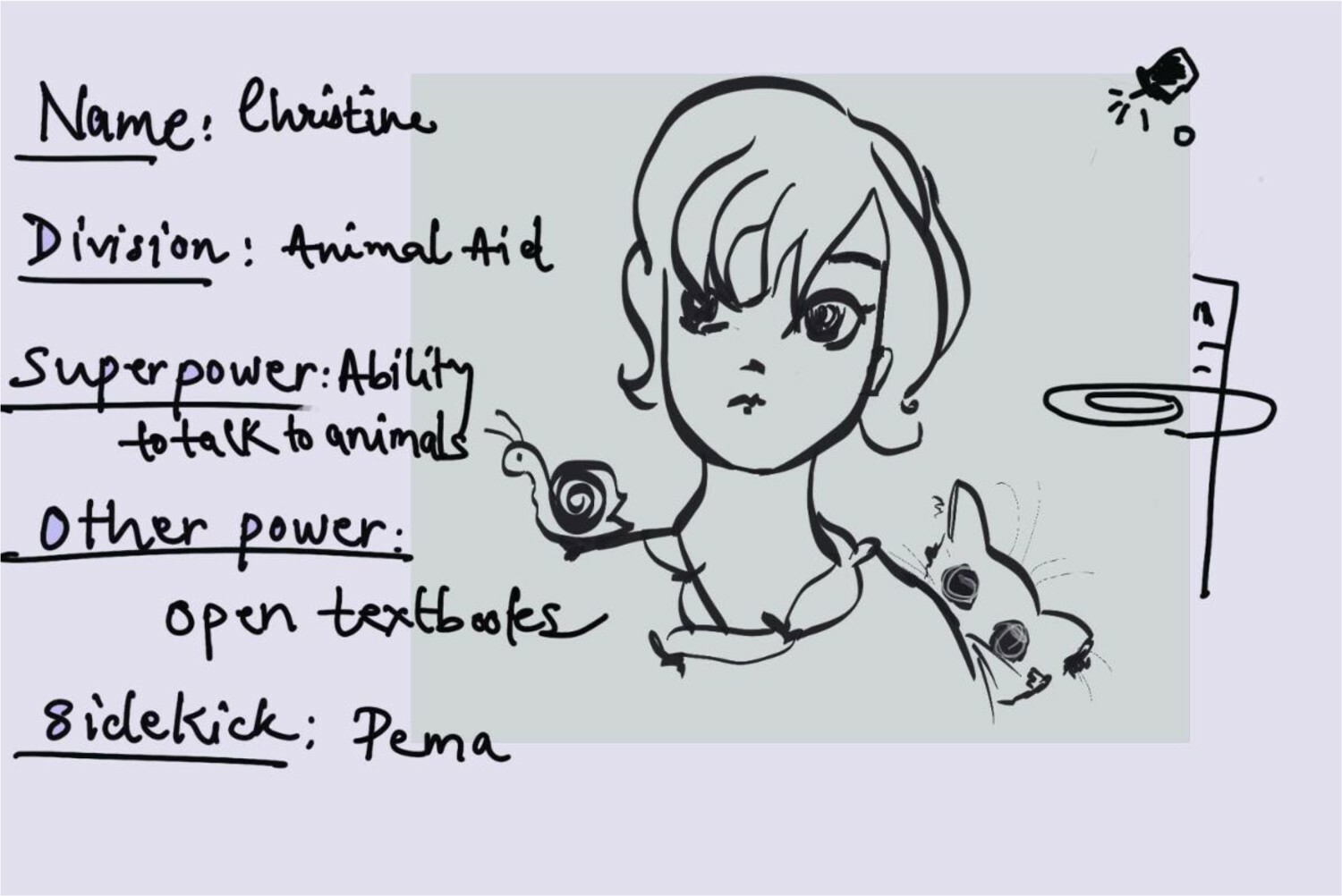

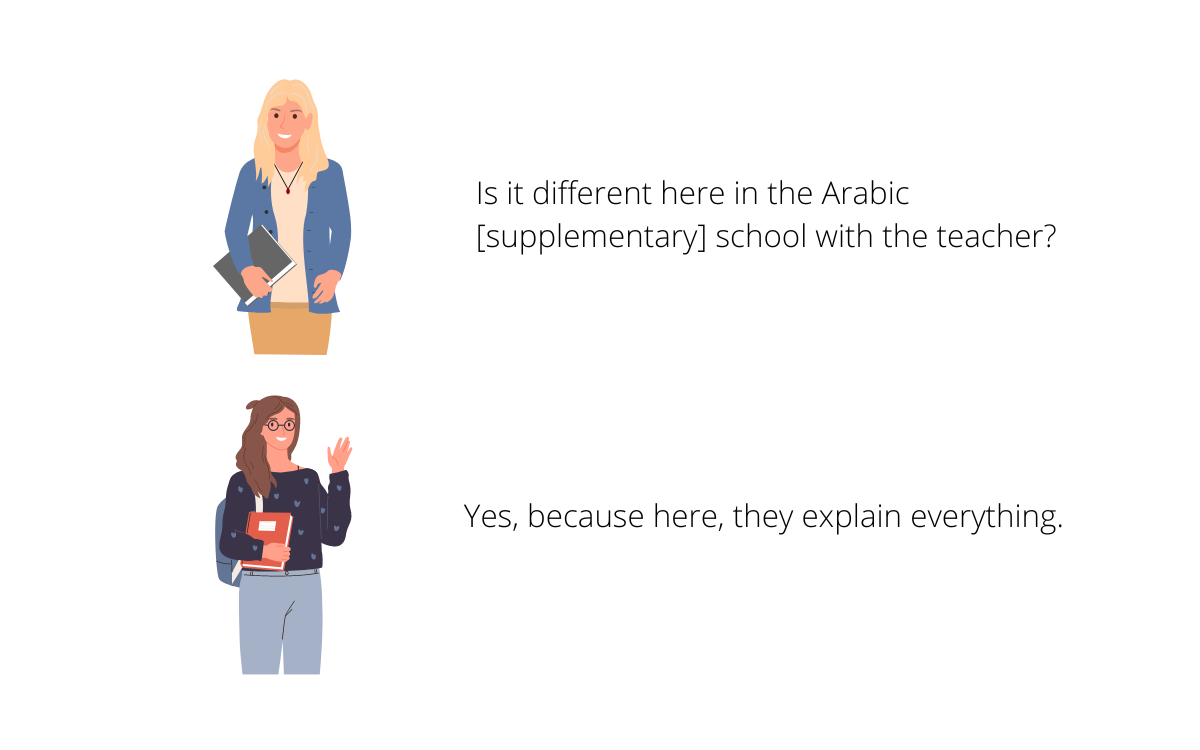

Student reflections

This is the response of a pupil when asked about the differences between her supplementary school and her Flemish mainstream school as part of a project investigating minoritized pupils’ views on the relationship to their teachers.

Some background – Minority students in Flanders, Belgium

Against a backdrop of persistent inequality in education throughout Europe, and in Flanders specifically, studies find that there is a gap not only in academic achievements between minoritized pupils and their peers, but also in the quality of student teacher relationships. The student-teacher relationship is of crucial importance to students’ educational pathways, yet teachers indicate feeling ill-prepared in teaching the diversity of their classrooms [1]. Students with a migration background tend to evaluate the relationship to their teachers as not as positive as their majority peers [2].

Other research has shown that some teachers hold ethnic prejudice towards their minority students [3], this is particularly worrisome as only a very small percentage of teachers in Flanders have a migrant background [4]. The difference in ethno-cultural background – called Ethnic incongruence [5] – between teachers and students in mainstream schools is often hypothesized as an explanation for the different evaluation of student-teacher relationships. What is currently missing from the research is the perception of those minoritized pupils.

Our research methods

Supplementary schools pose a unique vantage point from which to study minoritized pupils’ views on the student-teacher relationship. They are educational spaces [5] organized by minoritized communities to support their youth, usually take place during the weekend, and they often focus on teaching heritage language and culture. These schools are widespread, with as many as 45% of pupils in Flanders attending them at some point, as a yet unpublished paper by Coudenys and colleagues shows. That makes them particularly interesting to study in light of this project. After all, contrary to the mainstream Flemish schools in which most teachers are of white majority backgrounds, teachers in the supplementary school tend to share their pupils’ migrant backgrounds.

Pupils attending both mainstream schools and supplementary schools are in an exclusive position to compare two different settings and reflect on what is constructive to a strong relationship, in their experience. To this end, we conducted group interviews with 29 minoritized pupils in two supplementary schools. The pupils were between 9 and 12 years old and voluntarily decided to take part in the interviews, either alone or with a friend.

Our findings

To our surprise, we find that throughout all these interviews, in which the pupils recount and reflect on their relationship to their teachers in the mainstream Flemish school as well as in the supplementary school, not one of the pupils points towards the ethno-cultural background of the teachers. Rather, they give a nuanced depiction of their relationships in each context both on an academic and an emotional level. This is in line with other research [6] suggesting that children do not rely on ethnic categories to organize their world.

On an emotional level, the pupils indicate that they find the teachers in the mainstream Flemish schools to be less available to them overall. The children point towards factors such as class size to make sense of this lack of availability. Many of the pupils describe situations in which the teacher did not intervene in fights or altercations in the classroom, negatively impacting the quality of the relationship. The children are especially grateful to those teachers that show an interest in their cultural backgrounds. Some pupils remember teachers who asked about their supplementary schools fondly, while acknowledging that such interest is rare.

While there is not always a clear-cut difference in the pupils’ perception of the teachers from one context to the next, they do almost uniformly declare a difference in the support they receive academically. The pupils report that they are reluctant to ask their mainstream teachers for help because they expect to be turned down. The children relate how they keep their questions to themselves, and then ask their teachers in supplementary school to explain to them at the weekend.

Implications for practice, beyond Belgium

We conclude by highlighting some important implications of our findings. Importantly, there is ample research [7] that emphasizes the importance of diversity in teacher staff in terms of countering prejudice, academic expectations, role models and more. The findings of this project do not seek to diminish that importance. Rather, in a reality of ethnic incongruence in student-teacher relationships we make some suggestions to better support pupils of minoritized backgrounds. First, pupils appreciate curiosity from their teachers. Interest in their cultural backgrounds and, relatedly, asking questions about their experience in the supplementary school is clearly beneficial. Second, the pupils were very perceptive of the pressure their teachers experience, and therefore they found them less approachable. And third, there are ample resources available in the supplementary schools. There could be much gained from a meaningful exchange between these different educational contexts.

Key Messages

- Supplementary schools pose an interesting vantage point from which to study the perspectives of minoritized pupils.

- We study the student-teacher relationship from an academic and an affective dimension.

- Pupils describe that they feel better emotionally supported by their teachers in the mainstream school when they show an interest and open attitude towards their ethno-cultural background.

Julia Steenwegen

PhD Researcher

With past experience as a primary school teacher, Julia’s research focus is on inequality in education. Her main focus is on the resources in children’s networks that provide support in their educational pathways.

Orcid: 0000-0001-6743-9788

Other blog posts on similar topics:

[1] Berkovich, I., & Benoliel, P. (2020). Marketing teacher quality: Critical discourse analysis of OECD documents on effective teaching and TALIS. Critical Studies in Education, 61(4), 496-511.

[2] Agirdag, O., Van Houtte, M., & Van Avermaet, P. (2012). Ethnic school segregation and self-esteem: The role of teacher–pupil relationships. Urban Education, 47(6), 1135-1159.

[3] Van den Bergh, L., Denessen, E., Hornstra, L., Voeten, M., & Holland, R. W. (2010). The implicit prejudiced attitudes of teachers: Relations to teacher expectations and the ethnic achievement gap. American Educational Research Journal, 47(2), 497-527.

[4] Nulmeting herkomst leerkrachten in het Vlaamse onderwijs

[5] Thijs, J., Westhof, S., & Koomen, H. (2012). Ethnic incongruence and the student–teacher relationship: The perspective of ethnic majority teachers. Journal of school psychology, 50(2), 257-273.

[6] Steenwegen, J., Clycq, N., & Vanhoof, J. (2022). How and why minoritised communities self-organise education: a review study. Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education, 1-19.

[7] Sedano, L. J. (2012). On the irrelevance of ethnicity in children’s organization of their social world. Childhood, 19(3), 375-388.

[8] Goldhaber, D., Theobald, R., & Tien, C. (2019). Why we need a diverse teacher workforce. Phi Delta Kappan, 100(5), 25-30.