As children returned to school after the summer break in 2021, five small rural schools in Northern Ireland didn’t reopen their doors. What that means for the former pupils and their communities has barely been given any attention.

What is a ‘Rural School’?

Many small rural schools in different European countries were also forced to close last school year due to declining pupil numbers and financial pressures. In our recent review of the European research literature, we found that small rural schools have been defined in different ways.

While many definitions relate to the number of pupils enrolled (typically between 70 and 140 for primary schools), in the Republic of Ireland, for example, they are defined as schools employing four teachers or fewer. However, north of the border in Northern Ireland (United Kingdom), there is no official definition of small schools despite a history of small and very small schools in the region, partly because of its rural character and the segregated nature of the school system. In fact, in 1964, there were over 450 schools with between 26 and 50 pupils, although by the early 1990s, there were less than 150 schools with such number of pupils.

In 2006, an Independent Strategic Review of Education (otherwise known as the Bain review) indicated that there was an excess of schools in Northern Ireland because of falling pupil numbers and the existence of many school sectors. The review argued that there should be fewer, larger schools, and established that primary schools in rural areas should have at least 105 pupils enrolled. So, in the context of Northern Ireland, we understand a small rural school to be a primary school situated in a rural area (i.e., settlements with a population of less than 5,000 and areas of open countryside), with 105 pupils or less enrolled.

Small rural schools in Northern Ireland

There is scarce research on small rural schools in Northern Ireland, as most studies have concentrated on schools in urban areas. Between April and July 2021, we conducted an online survey of principals of small rural schools in Northern Ireland. Out of 201 principals invited, 91 took part (86 completed responses and 5 incomplete). In this post, we are sharing three themes that emerged when analysing the survey data.

1. SEGREGATED SCHOOLS SERVING SEGREGATED COMMUNITIES:

Northern Ireland society is segregated along ethno-sectarian lines between an Irish Catholic group and a British Protestant group. This is reflected in its school system, so most pupils from a Protestant community background attend Controlled (de facto state) schools (in which the Protestant churches have a formal role), and most pupils from a Catholic community background attend Voluntary Maintained schools, owned by the Catholic church. There is also a small number of integrated schools, which are attended by children and staff from Catholic and Protestant traditions, as well as those of other faiths, or none.

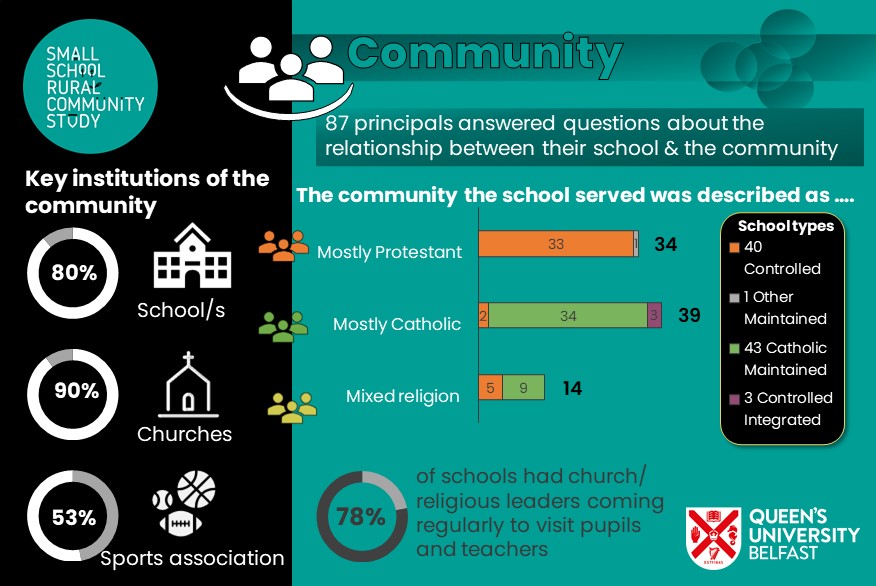

From the survey results, it was clear that the

schools were serving very segregated communities. Thus, the majority of Controlled school principals described the communities their schools served as mostly Protestant, and the majority of Catholic maintained school principals described them as mostly Catholic. Only a few described them as mixed or fairly mixed. Surprisingly, all three principals from integrated schools described their communities as mostly Catholic.

In both Catholic and Protestant rural communities, the churches appeared to have a significant role, with most principals (90%) identifying them as key institutions in the communities their schools served. However, we found a clear difference between school types. While 91% of Catholic Maintained school principals identified the sports association as another key organisation, only 12% of Controlled school principals did so. That is because in many Catholic communities, the GAA club is very influential. GAA stands for Gaelic Athletic Association, and it is Ireland’s largest sporting organisation (which promotes Gaelic games). Community voluntary groups and cultural associations were less likely to be identified by principals, and they were selected by a larger proportion of Controlled school principals rather than principals in Maintained schools.

2. CHALLENGES:

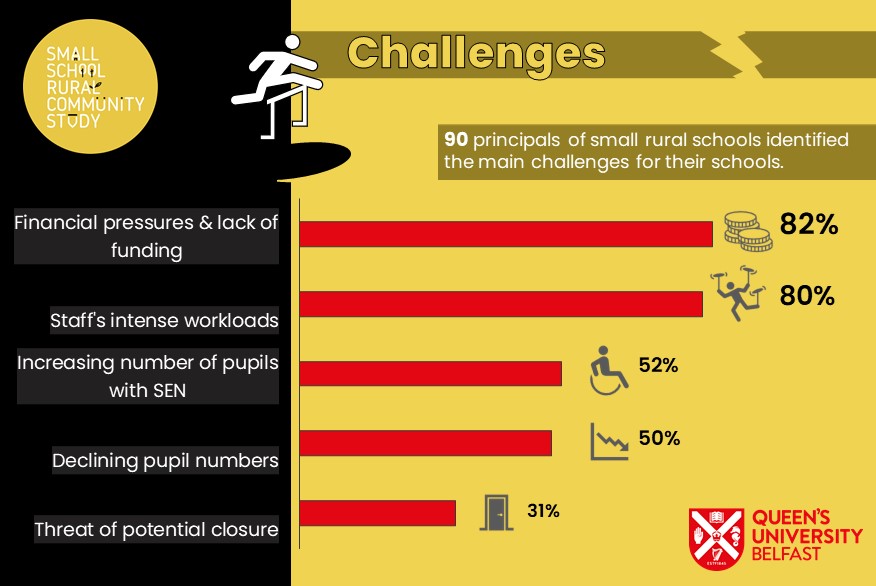

According to the principals surveyed, the main challenges these schools were facing were similar to those found in other research in different European countries. The ones that were most identified by the survey respondents were:

- financial pressures and lack of funding (selected by 74 out of 90)

- staff’s intense workloads (72)

- increasing numbers of pupils with special educational needs and disabilities (47)

- declining pupil numbers (45)

- pressure or threat of potential closure (28).

However, in contrast with other studies, difficulties in staff recruitment and retention were barely ever selected as current challenges (just two principals did).

Some of the comments written by principals highlighted the main challenges they encountered:

“… Our school, that twenty-thirty years ago would have had 7 straight classes, now is struggling with 4 composite classes. Our parents ARE supportive of our school but small numbers means we are struggling to survive in this community. ….”

“There is now so much paperwork and accountability not just educationally but from a health and safety and financial perspective that I feel the role of a teaching principal is no longer feasible.”

“Unfortunately, the threat of closure is ever present and this has stopped some families enrolling at the school thus resulting in a fall in our enrolment numbers which are hard to recover from. Our physical site also needs a lot of investment but this does not fail to materialise because of question marks over our future which results in the local community not having faith that our school will remain open and so they choose to travel further away.”

3. AT THE HEART OF THE COMMUNITY?

The connection between the schools and the families and wider community was generally described as strong. Most principals (80%) considered the school as a key institution or organisation of the community they served. This is also clear from many of the principals’ open-ended comments:

“Our school is the heart of the rural community. Our families often have no other outlet or community-based organisation to support them. We offer support for parents and work closely with community groups to offer social events. Many of our parents do not drive and have no public transport, meaning they live isolated lives apart from their connection to the school.”

“The local community is very important. Pre-pandemic we had good contact and well attended events. We had a great Mums and Tots group. Our PTA are fantastic at organising and promoting school events.”

“The school is a central part of our rural community. Enabling local groups to access our facilities assists local groups and clubs to exist.”

The most common ways schools engaged with the communities they served were:

- Church/ religious leaders coming regularly to the school to visit pupils and teachers (78%)

- Community leaders being on the board of governors of the school (77%)

- Pupils being actively encouraged in the school to get involved with particular community organisations (63%); and

- After-school (or outside of school hours) activities organised by community/sporting/religious organisations/institutions taking place on school grounds or being advertised by the school (64%).

We asked whether the pandemic had had an impact on the level of engagement of parents/families and the wider community with the school. As expected, most principals believed that the pandemic had a negative impact – 88% believed there had been less engagement between the school and the wider community, and 57% believed there had been less engagement between the school and parents/carers.

In conclusion, small rural schools in Northern Ireland face similar challenges as other small rural schools in Europe, but their situation differs mainly because of the segregated environment in which they are immersed. Also, small rural schools in NI are not a homogenous group. Some schools appeared to be experiencing more challenges than others, some have more resources than others or are considerably bigger/smaller, etc., and their community contexts are also distinct.

If you would like to find out more about our study, please visit our study blog.

Montserrat Fargas-Malet

Research Fellow

Montserrat Fargas-Malet is a Research Fellow at the School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University Belfast. Her background is in Sociology (BSsc), Women’s Studies (MA), and Education (PhD). She has over 15 years of experience in social science research and an excellent publication record.

Professor Carl Bagley

Professor of Educational Sociology

Carl Bagley is Head of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work at Queen’s University Belfast where he holds a Chair in Educational Sociology. He has held research posts at the National Foundation for Educational Research (NFER) and the Open University (where he obtained his PhD) and previously held a Senior Lectureship in Sociology at Staffordshire University, before Joining Durham University in 1999, obtaining a Chair in 2008 and serving as Head of the School of Education from 2013-2017.