How can teachers make a difference in climate change education?

Student: Teacher, I want to play with snowballs, but it’s not snowing. My Mom said that it used to snow a lot at this time of year.

Teacher: Your Mom is right. It’s December! We’re used to snow in winter, but we haven’t had any this year.

Student: Why isn’t it snowing now? What’s happening to the seasons?

Teacher: What you’re noticing is climate change. We need to explore it to protect our planet.

The above dialogue illustrates that climate change is no longer a distant concern; it has become a reality we experience firsthand. From unseasonably warm days to extreme weather events, we are becoming more aware of the changes happening around us. Research has confirmed that long-term shifts in temperatures and weather patterns are occurring. The United Nations (2023) reports that the Earth’s average surface temperature is now about 1.2°C warmer than it was before the industrial revolution. It is now well recognized that human activities that increase greenhouse gas levels in the atmosphere contribute to climate change (World Meteorological Organization, 2024). The human impact on climate change highlights the importance of education as a strategic tool for promoting environmentally responsible behaviors to help mitigate its effects.

Teachers undoubtedly play a key role in climate change education. While many teachers may think that only science or geography educators can tackle climate change, research reveals that it’s a cross-disciplinary topic that can be woven into every subject (Tibola da Rocha et al., 2020). But how can teachers effectively respond to climate change and create a meaningful impact? In this blog post, we outline the key principles of effective climate change education.

The importance of teacher education programs

To address climate change effectively, teachers need to embrace evidence-based strategies that target two crucial areas: mitigation and adaptation (Anderson, 2012). To effectively guide students in these areas, however, teachers themselves must first be strongly aware of climate change – the causes, the impacts, and the strategies for both mitigation and adaptation. Given that many teachers struggle with inadequate preparation in both knowledge and practical approaches for engaging their students in addressing the climate crisis (Beach, 2023), teacher education programs and professional development initiatives become essential in bridging this gap. These programs can serve as powerful catalysts, providing educators with the insights, strategies, and confidence they need to tackle climate change. learning.

Greening the curriculum

While teacher education is crucial, so is the effort to green the curriculum. A well-designed curriculum empowers teachers and strengthens their impact on students. According to UNESCO (2024), effective climate change education requires a green curriculum that covers diverse aspects of climate change, integrates relevant local knowledge, and emphasizes learner-centered, experiential, and reflective learning approaches. Equally important is how teachers bring the curriculum to life in the classroom. Teachers who are effectively prepared for climate change education go beyond simply delivering facts; they help students understand climate challenges deeply, reflect on their consequences, and explore ways to contribute to solutions (Stevenson, Nicholls, & Whitehouse, 2017).

Using the bicycle metaphor as a framework to address climate change education

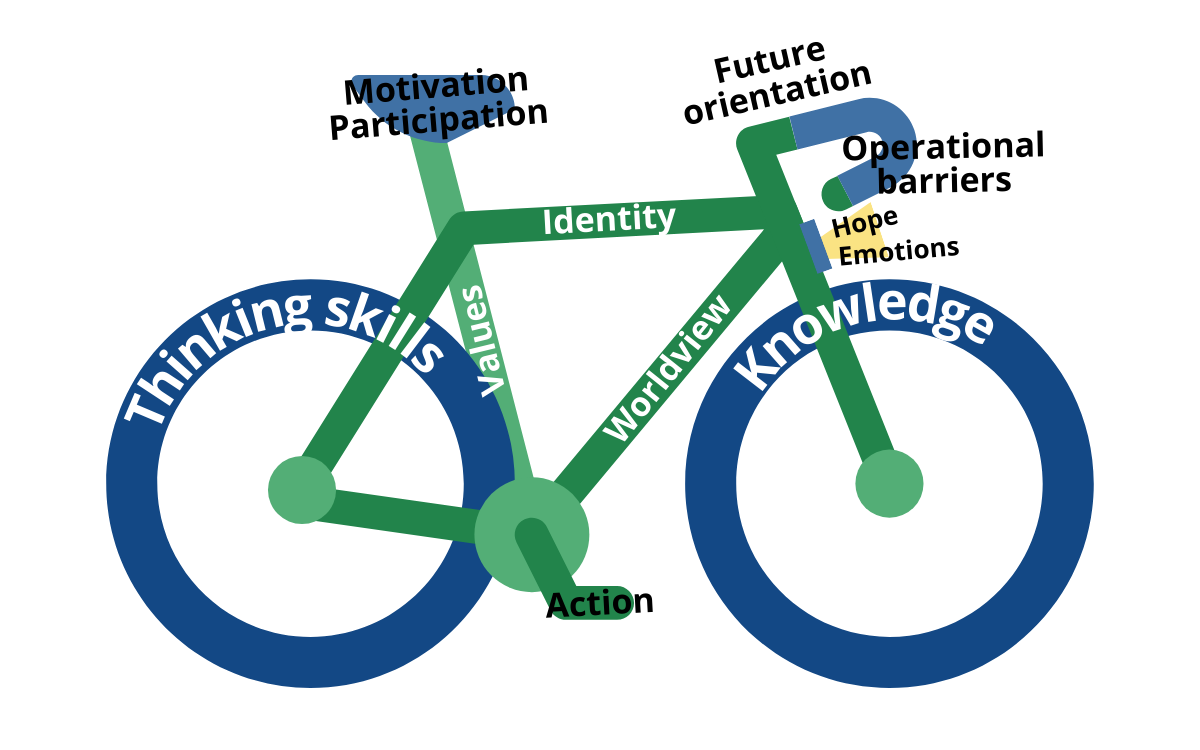

The bicycle metaphor of Cantell et al. (2020) provides a valuable framework for teachers in shaping their approach to climate change education.

Wheels: the foundational knowledge and thinking skills necessary to address climate issues.

Pedals: highlight the action-oriented aspect of climate change education, where knowledge is transformed into meaningful change.

Lamp: underscores the importance of emotions and hope for climate change education, reminding teachers to nurture emotional awareness and resilience in their students.

Frame: symbolizes the core values that shape how students understand and engage with climate challenges.

This holistic approach encourages teachers to integrate knowledge, action, emotions, and values into their lessons.

As Bentz (2020) emphasized, it is vital that teachers discover effective ways to engage young people with a topic that often feels abstract, distant, and overwhelmingly complex, while also addressing the feelings of sadness, hopelessness, and anxiety it can evoke. Rousell and Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles (2020) indicated that didactic approaches to climate change education have proven largely ineffective in influencing students’ attitudes and behaviors. Thus, shifting away from traditional lecture-based teaching toward more interactive and creative methods is essential for meaningful climate change education in schools. Research by Monroe and colleagues (2019) offers valuable insights into strategies that can make climate change education truly impactful. At the heart of these strategies is promoting student reflection and active engagement to understand the causes and consequences of climate change, while also empowering them to explore adaptation and mitigation strategies, and take necessary actions.

4 actionable approaches teachers can use to address climate change education

- Foster meaningful discussions: Create opportunities for students to discuss climate-related issues openly, share their perspectives, and learn from one another.

- Connect students with scientists: Invite experts into your classroom to help students learn about climate science firsthand and encourage them to ask questions to deepen their understanding.

- Tackle misconceptions: Address common misunderstandings about climate change and guide students toward evidence-based knowledge.

- Support project-based learning: Encourage students to work on projects that connect classroom learning to real-world issues, whether through school initiatives or community-based efforts.

As part of these approaches, teachers can take advantage of integrating technology into learning. Research shows that technology-enhanced games and simulations can significantly impact awareness about climate change (Creutzig & Kapmeier, 2020). For instance, NASA (2025) has created a website called ClimateKids, which includes games, activities, and videos, making it a valuable resource for teachers.

The importance of collective climate action with and beyond the school community

Finally, it is important to highlight that while teachers’ approach to climate change education matters, their impact can be significantly amplified when other stakeholders such as principals, school staff at all levels, families, and community members are actively involved in the process. This whole-institution approach reinforces the idea of collective climate action and fosters a unified effort toward meaningful change (Hargis et al., 2021). Teachers, aware of the significance of collective action, can take the lead in building partnerships, encouraging collaboration, and creating opportunities for these stakeholders to contribute to climate change education. Drawing on the leadership and guidance inherent in their profession, teachers can empower students to become informed, responsible, and active individuals committed to building a sustainable future.

Key Messages

- Climate change is an urgent and undeniable reality, with human activities driving rising temperatures and environmental threats.

- Teachers are in a strategic position to inspire the behaviors needed to mitigate its impacts and promote a more sustainable future.

- Climate change education should extend beyond simply presenting facts. Teachers must integrate knowledge, critical thinking, action, emotions, and values to foster meaningful engagement and empower students to actively contribute to climate change solutions.

- Teachers need to find effective ways to teach climate change, adopting approaches that engage students in meaningful, interactive, and creative ways, rather than relying on traditional lecture-based methods.

- A whole-institution approach fosters collective climate action, with teachers playing a key role in building partnerships and encouraging collaboration among all stakeholders, including principals, students, families, and community members.

References and further reading

Anderson, A. (2012). Climate change education for mitigation and adaptation. Journal of Education for Sustainable Development, 6(2), 191-206. https://doi.org/10.1177/09734082124751

Beach, R. (2023). Addressing the challenges of preparing teachers to teach about the climate crisis. The Teacher Educator, 58(4), 507-522. https://doi.org/10.1080/08878730.2023.2175401

Bentz, J. (2020). Learning about climate change in, with and through art. Climatic Change,162(3), 1595-1612. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10584-020-02804-4

Cantell, H., Tolppanen, S., Aarnio-Linnanvuori, E., & Lehtonen, A. (2019). Bicycle model on climate change education: Presenting and evaluating a model. Environmental Education Research, 25(5), 717-731. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2019.1570487

Creutzig, F., & Kapmeier, F. (2020). Engage, don’t preach: Active learning triggers climate action. Energy Research & Social Science, 70 (101779), 1-7. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.erss.2020.101779

Hargis, K., McKenzie, M., & Levert-Chiasson, I. (2021). A whole institution approach to climate change education: Preparing schools to be climate proactive. In R. Iyengar and C. T. Kwauk (Eds), Curriculum and learning for climate action: Toward an SDG 4.7 roadmap for systems change (pp. 43-66). Boston: BRILL. https://doi. org/10.1163/9789004471818

Monroe, M. C., Plate, R. R., Oxarart, A., Bowers, A., & Chaves, W. A. (2019). Identifying effective climate change education strategies: A systematic review of the research. Environmental Education Research, 25(6), 791-812. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2017.1360842

NASA. (2025). ClimateKids. https://climatekids.nasa.gov/climate-change/.

Rousell, D., & Cutter-Mackenzie-Knowles, A. (2020). A systematic review of climate change education: Giving children and young people a ‘voice’and a ‘hand’in redressing climate change. Children’s Geographies, 18(2), 191-208. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2019.1614532

Stevenson, R. B., Nicholls, J., & Whitehouse, H. (2017). What is climate change education? Curriculum Perspectives, 37, 67-71. https://doi.org/10.1007/s41297-017-0015-9

Tibola da Rocha, V., Brandli, L. L., & Kalil, R. M. L. (2020). Climate change education in school: knowledge, behavior and attitude. International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education, 21(4), 649-670. https://doi.org/10.1108/IJSHE-11-2019-0341

United Nations. (2023). What Is climate change? https://www.un.org/en/climatechange/what-is-climate-change

UNESCO. (2024). Greening curriculum guidance: Teaching and learning for climate action. https://doi.org/10.54675/AOOZ1758

World Meteorological Organization (2024). State of the climate 2024: Update for COP29.https://library.wmo.int/records/item/69075-state-of-the-climate-2024

Hasret Baş

Student, Sinop University, Türkiye

Hasret Baş is a master’s student in the field of Curriculum and Instruction at Sı̇nop University, Türkiye. Her research interests include climate change education and curriculum studies. She is currently writing a thesis on climate change education and also works as a teacher in a public school.

İlknur Özbebek

Student, Hacettepe University, Türkiye

İlknur Özbebek is a doctoral student in Curriculum and Instruction at Hacettepe University, Türkiye. Her research interests include culture, ethnomathematics, curriculum and instruction. She is currently working as a research assistant at Sinop University.

Dr. Rahime Çobanoğlu

Associate Professor of Curriculum and Instruction, Sinop University, Türkiye

Rahime Çobanoğlu is an Associate Professor of Curriculum and Instruction at Sinop University, Türkiye. Her research interests focus on teacher practices, curriculum implementation, and teacher beliefs. She is currently supervising a thesis on climate change education.