COVID-19 pandemic and the mental health and well-being of secondary school children

This blog piece discusses the main findings from a research project funded and supported by York St John University and Liverpool Hope University into the impact of the Covid-19 pandemic on young people’s mental health and wellbeing. Our research suggests that the pandemic and associated restrictions and disruptions exacerbated an already serious situation for children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing (Wood, Su and Pennington, 2024)

The study

To gain an understanding of young people’s wellbeing, it is essential to access the views of young people themselves (The Children’s Society, 2022).

A National Health Service (NHS) study in the UK shows that before the COVID-19 pandemic, increasing numbers of children and young people were experiencing poor mental health and wellbeing (Newlove-Delgado et al., 2022). Our research drew on the views of young people about the development of factors conducive to their wellbeing and mental health in school and the sorts of factors that enable this.

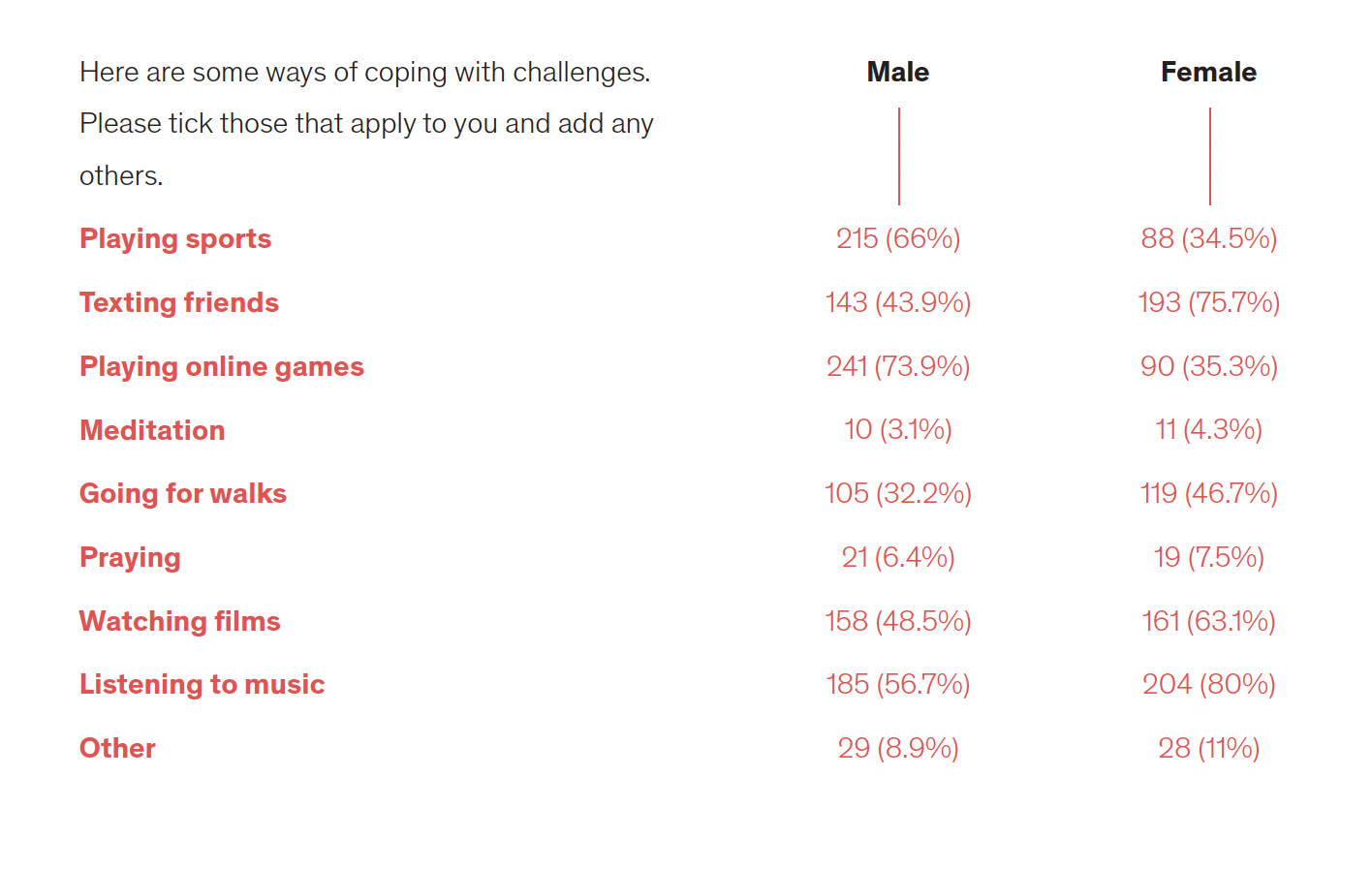

A qualitative multi-method research design was used, consisting of an online questionnaire survey (n=605) and follow-up focus group interviews (n=16). The research took place in three secondary schools in one local authority area in England. Year 9 and Year 10 students aged between 14 and 15 years from these schools participated in the study.

The study addressed the following questions: to what extent has the Covid-19 pandemic affected secondary school students’ mental health and wellbeing in England? What do students value most for their mental health and wellbeing in a secondary school context during the pandemic? What are the implications for the post-pandemic future?

Findings

The analysis evidenced the social and emotional impacts of a number of other factors too including anxieties about family members’ employment security, health and circumstances at home during the pandemic on young people’s mental health.

Significantly, transition back to in-person schooling brought its own challenges. One particular message that emerges from this study is that in the return to in-person schooling, the dominant emphasis on ‘catching-up’ to make good the learning loss, appears to have been too restricted and narrow and in need of an accompanying focus on: the restoration and regeneration of friendships and social bonds that lie at the heart of schools as communities and human flourishing; and sports/physical activity, arts and cultural pursuits .

The findings of the study show that the pandemic and associated restrictions had a detrimental effect on the lives of a very large proportion of the young people in our study, with a greater impact on girls than boys. From the analysis, the resilience and ability of the participants to ‘bounce back’ from the upheavals caused by the restrictions was apparent. However, for a significant minority, the adverse impacts on their mental health and wellbeing continue to affect their lives.

Findings suggest the Covid-19 pandemic had a bigger impact on girls than boys, for example:

- The reported impact on daily life was greater for girls ( 85%) than for boys (71%)

- The continuing impact was greater for girls (37%) than boys (24%)

- Friendships were more adversely affected for girls (54%) than boys (34%)

- More girls reported an adverse effect on mental health and wellbeing (55%) than boys (25%)

- Fewer girls felt supported by school (64%) than boys (79%)

Due to the scope of our study, specific reasons for the gender differences were not established. However, our study does suggest that there is a need for a holistic response to young people’s mental health and wellbeing issues, which gives prominence to addressing the gendered impact and recognises the importance of friendships, social bonds, arts, cultural and sports activities as well as the more academic domains of schooling.

Wider implications – insights from experts in the field

Findings and implications from the research have been widely shared at a number of briefings with school senior leaders, children’s services agencies, youth work organisations, and other partners from the local authority area in which the research took place.

In addition, the findings are being used to inform the annual report of the local Director of Public Health. The principal dissemination event to discuss our study findings with national and regional stakeholder groups was the ‘Symposium on Young People’s Mental Health and Wellbeing’, which took place in York on 19th March 2024. At the Symposium event, important insights were shared by the following expert panel members.

Anne Longfield, Chair of the Commission on Young Lives, UK, argued there is a need for joined up services and cross agency working to support children’s education and mental health and an extended role for schools in their communities. She stated that ‘I, for a long time, have been a big proponent of schools being fully open to their communities and making their precious resources more accessible to children and families’.

Alison O’Sullivan, Chair of the National Children’s Bureau, UK, suggested that the social contract between schools, parents and children has broken down and stressed the importance of renegotiating the relationships between children and families, communities and schools. She also expressed that ‘evidence increasingly demonstrates that children and young people’s sense of belonging plays a decisive role in shaping their social, emotional and mental health outcomes’.

Charlotte Rainer, Coalition Manager at The Children and Young People’s Mental Health Coalition, UK, suggested two possible solutions – firstly, to increase early intervention support with dedicated funding; secondly, to create children’s mental health and well-being drop-in hubs in the community.

Dan Bodey, Inclusion Adviser, City of York Council, UK, observed that ‘school attendance has been significantly low since the Covid-19 pandemic particularly for children who have special education needs (SEN) and those who are on free school meals. In addition, the school exclusion rate has increased noticeably’. He also highlighted the importance of cross agency working to address these issues as part of post-pandemic recovery.

Conclusion

This study shows that the pandemic and associated restrictions had a detrimental effect on the lives of a very large proportion of the young people in our study, with greater impact on girls than boys. These effects have significant implications for the ways in which school and services develop their responses to the question of children and young people’s mental health and wellbeing.

Key Messages

Overall, the principal insights affirmed the importance of:

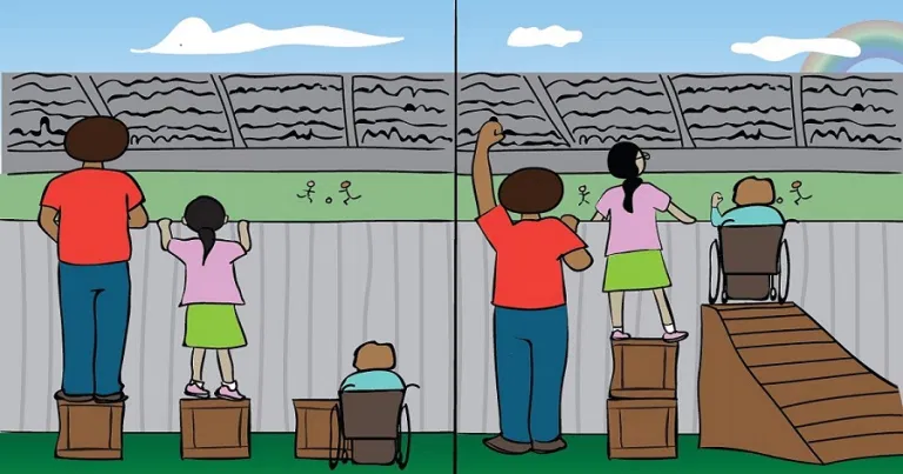

· responding to the continuing adverse effects on mental health and wellbeing for a significant minority of young people, taking account of the gendered nature of these impacts

· ensuring young people’s voices are brought into decision making and policy formulation

· easily accessible early help and support

· inclusive educational practices to strengthen a sense of belonging for all children and placing children’s mental health at the heart of education provision.

· an inclusive curriculum which focuses on the whole person rather than an overemphasis on academic achievement and high stakes assessment and testing.

Dr Margaret Wood

Senior Lecturer in Education at York St John University, UK

Dr Margaret Wood is a Senior Lecturer in Education at York St John University, UK. Her recent research and publications have explored the centralizing tendencies of much current education policy and its relation to community and democracy at the local level, and the development of academic practice in higher education.

Dr Feng Su

Associate Professor and Head of the School of Education at Liverpool Hope University, UK

Dr Feng Su is an Associate Professor and Head of the School of Education at Liverpool Hope University, UK. His main research interests and writings are located within the following areas: education policy, the development of the learner in higher education settings, academic practice and professional learning.

Dr Andrew Pennington

Post-doctoral researcher at York St John University, UK

Dr Andrew Pennington was a senior officer in two local authority education and children’s services departments. He is now a post-doctoral researcher at York St John University, UK. His main research interests are concerned with democracy, power and community engagement in the governance of schools.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

The Children’s Society (2022). The Good Childhood Report 2022. The Children’s Society. https://www.childrenssociety.org.uk/sites/default/files/2022-09/GCR-2022-Full-Report.pdf

Newlove-Delgado, T., Marcheselli, F., Williams, T., Mandalia, D., Davis, J., McManus, S., Savic, M., Treloar, W. & Ford, T. (2022). Mental Health of Children and Young People in England 2022. NHS Digital. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/mental-health-of-children-and-young-people-in-england/2022-follow-up-to-the-2017-survey

Su, F., Wood, M. and Pennington, A. (2024). ‘The new normal isn’t normal’: to what extent has the Covid-19 pandemic affected secondary school children’s mental health and wellbeing in the North of England? Educational Review. DOI: 10.1080/00131911.2024.2371836