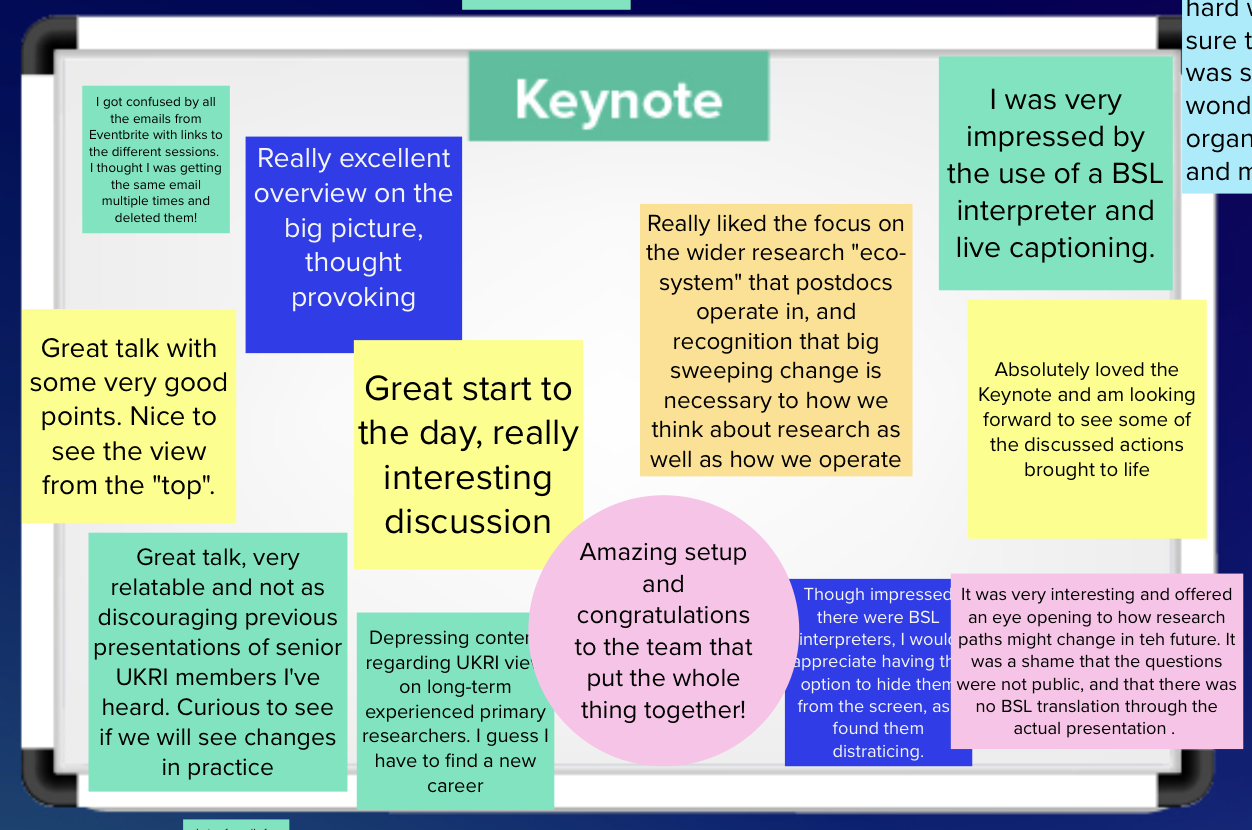

ECER 2021 Geneva will focus on ‘Education and Society: expectations, prescriptions, reconciliations’. How relevant is this theme today in this specific context? Why is the city of Geneva a fertile ground in the field of education and of the development of the individual for hosting debates on reconciling societal expectations (sometimes disparate, diffracted or even contradictory) with the realities on the ground, and the needs of those involved in education, teaching and training?

This contribution from Dr Stefan Bodea aims to provide some socio-historical and cultural milestones which should support decanting the essence of the Geneva call for contributions covering this theme: an ‘urgent’ call, of fairly obvious topicality, stemming above all from the need to understand the tensions, resistances, pressures and cleavages with which the educator/teacher/trainer is confronted on a daily basis.

Education for All and its endeavours

Thanks to the decree of the Reformation, the birth of the Republic of Geneva (21 May 1536) coincided with the creation of the first compulsory and free public school in the world. Elementary education in Calvin’s City thus became accessible to and free of charge for all, regardless of the pupils’ status, and “the invalid, the orphan, the widow, the old man, and any need for assistance is taken into consideration in the same spirit”[1].

In the collective memory, this historical vocation of the Geneva educational institution even outweighs its other assets, such as the international reputation of its teachers[2]. Indeed, as Joy Kündig notes, “the most important aspect of Calvin’s Academy is not the great names of its teachers or students, but the fact that it really contributed to the democratisation of studies […] In Geneva, education was really for everyone” (Kündig, J., op.cit., p. 59).

However, although Geneva is generally considered to have successfully met this challenge, this success has always required, for the education actors engaged in this democratisation process, the handling of numerous tensions between expectations and feasibility, between injunctions and realities on the ground, between official prescriptions and the real needs of the students and educators. From this point of view, it can be argued that teachers should be considered as divided actors, ‘plural individuals’ as the sociologist Bernard Lahire would say; not insofar as self-unity would be an illusion, but because of the heterogeneity and the often-contradictory nature of the expectations that guide their social actions. Whether they are experienced as professional ‘sufferings’ or as structuring challenges of the educational praxis, these expectations seem to render more complex, or even make more difficult, the necessary construction of what Jacques Ardoino[3]calls the “authorisation capacity” as a process of “progressive and continuous creation of the self, both of social as of personal origin”, which is to be distinguished from “complacency in conformity, and therefore from the tendency to reproduce, characteristic of social practices which are artificial by dint of wishing to be only professional, strategic and technical”.

For the societal call for the creative accomplishment of educational action seems itself contradictory in that it is a matter of both “learning to enter the order of the law” and “developing the capacity for transgression”, which characterise the “impossible and yet necessary” professions[4].

From this point of view, ECER 2021’s invitation to reflect on and work towards the reconciliation of ‘divided’ socio-political/socio-cultural/socio-economic demands implies, among other things, working on the concrete modalities that today allow for socially meaningful, legitimate and acceptable articulations and adjustments of the different positions, roles, attitudes, experiences, convictions, options… of the actors concerned.

But what are the forces likely to generate such adjustments? They will undoubtedly be listed, discussed in detail, questioned and dealt with within the 33 EERA networks. We will limit ourselves here to pointing out essentially two of them, which fall within the scope of two types of problems widely shared by the actors in the field of education.

– The first concerns the need to work towards inclusive education that is permeable to difference and diversity, while ensuring a balance for all, through shared values and practices. In concrete terms, this means, among other things, that the school system can no longer “presuppose of all the pupils it welcomes what only some of them have built up before and outside their school experience and not to build it up explicitly in those who do not have it”[5]. We are indeed dealing with the issue of the equitable educational provision and the construction of common bases and habitus, concerned with considering the differential particularities of educational support and, in general, the heterogeneity of the social, political and cultural environment.

– The second has to do with the relationship between the requirements formulated by educational policies and the real needs of learners/students, taking into account the expectations of civil society. This is seriously considered in Geneva, where teaching, from the outset, has been thought to be directly linked to practice. In this respect, we should not forget the importance given in Geneva to the empirical and experimental paradigms that developed in Europe at the end of the 19th century in educational sciences.

Nevertheless, it must be admitted that nowadays, in the field of teacher education, this articulation is the subject of numerous debates, particularly with regard to the relationship of trainees to the academicisation of training, following the importance given to research in recent times. Beyond the variations of the relationship between training and academic research (which can be broadly grouped into two categories: training by and respectively to or for research), this phenomenon seems to produce painful effects on the trainees’ side; when certain aspects of the theoretical content prove to be of little use in the exercise of their profession or do not immediately show the empirical interest of their exploitation. Consequently, looking into the empirical potential of the conceptual systems used in training, in line with the specificities and needs of the field, emerges as an important subject for further reflection and study.

While there are many demands on teachers and trainers, pupils/students are also affected, albeit at different levels. They have to deal with, among other things, the thickness of the different institutional expectations, which are sometimes not fully harmonised or are already divided at the inter-institutional level; the pressure of certificate-based assessment (the frequency of certificate-based assessment practices specific to certain teaching systems could even suggest that in the educational economy there is more assessment than teaching); the impact of the health crisis on the current situation of young people, which undermines the mission of social workers notably, etc., is the icing on the cake[6].

The Geneva student, like an athlete in competition, is above all a student who must accept a double contract: training and academic endurance. Seen from this angle, his or her work is unquestionably part of the Geneva history of academic requirements, which reminds us of a memorable reply addressed by Theodore de Bèze to the father of one of his boarders[7]: “I fear that nothing good will ever come of your son, for in spite of my prayers, he does not want to work more than fourteen hours a day” (p. 78).

Education Nouvelle and the interest of the main questions it raises

At the beginning of the twentieth century, Geneva advocated an educational renewal that placed at the centre of its investments the study of the child, the laws that ‘govern’ his or her development, his or her needs and potentialities… Despite the difficulties in reconciling its assumptions with those of education sciences, this trend, fuelled perhaps more by reformist hopes than scientific challenges, has generated and continues to generate numerous reflections on the centrality of the pupil, on his or her development but also on the pupil as an object of study. Some of these ideas might be more fruitful; others seem to be more risky.

This ‘Copernican revolution’, as Edouard Claparède described the Education Nouvelle programme, essentially oriented by experimental projects, has not only had moments of fervour; it has also been questioned, debated and even accused. No doubt because of the emphasis given to the talents, interests and psychological predispositions of the pupil.

Today, the promises, opportunities and interest of this international movement[8] are being studied, researched and assessed. The aim is to understand its actual and/or potential contributions to the development of educational sciences, teacher training and research, apart from the numerous school reforms to which this movement has given rise.

In 2018, the LIFE laboratory of the University of Geneva organised a study day[9] of immense scientific interest, which deserves particular attention for the quality of the issues and debates raised, beyond the polemics that they may cause. The main argument of this event, by virtue of the questions it raises, invites a careful analysis of the real and potential contributions of New Education to the evolution of ordinary teaching practices. As the text of the argument suggests, this analysis cannot avoid the [three] major criticisms made of it (the weakening of school authority, the concealment of knowledge and the naturalisation of pupils’ difficulties and inequalities):

One hundred years later, what remains of this hope? Is it outdated, even old-fashioned? On the contrary, is it necessary, because it was never realised? Or neither, because practices never evolve as ideals would like, but never without reference to them either? / […] what assessment can be made of the promises kept or aborted? Slogans such as “the pupil at the centre”, “the tailor-made school” or “teaching is learned” have been (and still are) alternately accused of undermining the authority of the school and of teachers, of hiding knowledge or erudition under activities, of naturalising difficulties and inequalities.

Education Nouvelle raises questions, doubts, debates and critical analysis concerning teaching practices. It, however, also allows for extremely useful reflections in terms of research and of the construction of training systems based on scientific and experimental contributions relating to the study of the pupil (more precisely, to the study of what Christian Orange calls the ‘intellectual activity of the pupil’[10]).

The flagship programme envisaged by Edouard Claparède in his landmark work ‘Child Psychology and Experimental Pedagogy’ (1905) is in many respects echoed in research focused on the analysis of the cognitive activity of the pupil and the organisation of his or her actions within the framework of the specific school tasks. In this context, probing the student’s interests in order to better respond to his or her needs, means above all converting these interests into levers for the diagnosis and treatment of learning/educational/developmental needs, as anchored in the formalised expectations of the educational system. This aspect is of great importance in the training of teachers, centred on the study of the pupil, insofar as it makes it possible to distinguish between needs belonging to the private/intimate sphere and objectively identifiable educational needs, in order to better articulate them, when their articulation is possible and, above all, necessary.

In this respect, the invitation of the ECER 2021 scientific committee to focus on the issue of the tensions between, on the one hand, “the stated aims of formal education” (insofar as they are the result of a “collective, mandated endeavour”) and, on the other hand, “the realities or social contexts within which the education process takes place”, seems to us to be of great interest and of great international relevance, as it can be witnessed by the reality in Geneva.

Indeed, educating, teaching, training, in a multicultural context such as that of the City of Calvin, are missions that are difficult to think about without a certain mastery of the social conditions that allow the construction of living together as the main entry point in the formation and development of the citizen, but also in the resolution of social problems.

In summary, this is what allows us to say that a theme such as that of ECER 2021 could not be better received than in Geneva, the home of reconciliation, probably “the most conducive to happiness”, to quote Jorge Luis Borges’ memorable phrase.