Developing a Classroom Tool to Promote Critical Perspectives on ‘Single Stories’

EERA is delighted and honoured to be partnering with the Global Educational Network in Europe (GENE) to make significant research funds available to our members to further research the area of global education. We asked the recipients of the Global Education Award 2020/21 to share their research with the broader EERA community.

In 2009, the Nigerian author, Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie, delivered a Ted Talk about what she called The Danger of a Single Story. Adichie’s central theme is that how stories are told, who tells them, when and how, is ‘really dependent on power’. She illustrates this by drawing on her own experiences of being subjected to single stories about Africa as a place of ‘catastrophe’ and juxtaposing this with examples of the single stories she has held about others.

So that is how to create a single story, show a people as one thing, as only one thing, over and over again, and that is what they become.

Chimamanda Ngozie Adichie, 2009

Adichie’s talk was translated into 45 languages and clearly resonated deeply with many people. In common with other educators with an interest in facilitating Global Citizenship Education (GCE), we (the two researchers) found it useful to use The Danger of a Single Story as a stimulus for conversations about challenging prejudice and stereotypes.

We became interested in how this could be supported by developing a tool for exploring global issues critically from different perspectives on how the world is. Building on previous research on teachers’ experiences with GCE (Franch, 2020), we were influenced by Vanessa Andreotti’s (2010) ideas on developing critical literacy to pluralize ways of knowing, and possibilities for thinking and practice. Andreotti’s ideas have also been significant in developing GCE as a form of critical pedagogy; influencing our use of the term ‘critical GCE’ here (Blackmore, 2014).

Whilst ideas about critical GCE are generally familiar to those working in the field, we were aware of concerns about the lack of opportunities for teachers to engage with these in practice (Blackmore, 2014; Pashby and Sund, in Bourn, ed. 2020). For instance, we knew The Danger of a Single Story might be popular with teachers, but we were less clear about whether and how far they might use it to promote critical GCE. We aimed to develop a tool to support the use of Adichie’s talk, which could be explored with teachers. As educators based in Italy and the UK, we were also interested in comparing responses between two different European contexts.

Developing the ‘Single Story’ tool

To begin developing the tool, we drew on existing ideas and frameworks developed with similar aims in mind. These ranged from tools like the Development Compass Rose and Andreotti’s (2006) framework for distinguishing between ‘soft’ and ‘critical’ GCE, to more recent work on applying her HEADS UP tool in classrooms, developed into a resource for teachers. Whilst acknowledging these developments, and not wanting to ‘reinvent the wheel’, we felt there was space for a tool which could support responses to Adichie’s Single Story specifically.

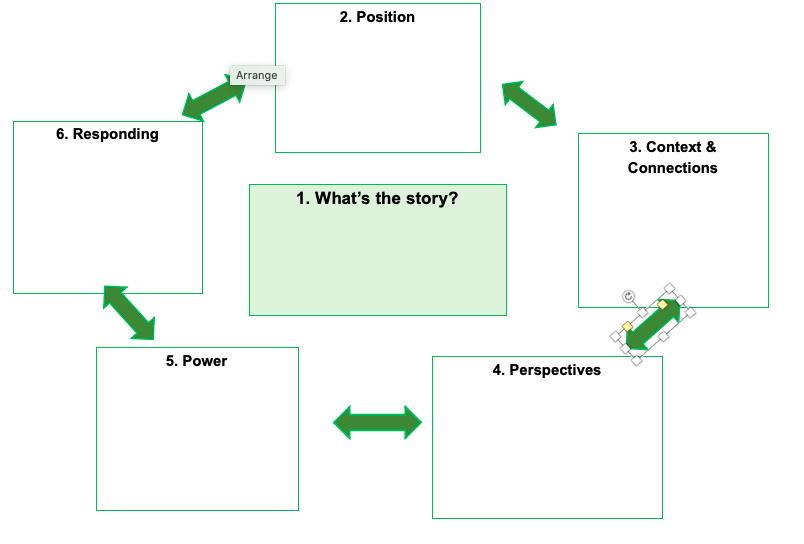

We devised a series of six themes or ‘lenses’ through which different questions could be applied to any issue identified as a Single Story. This might be represented by an image, text, film clip, or even an object.

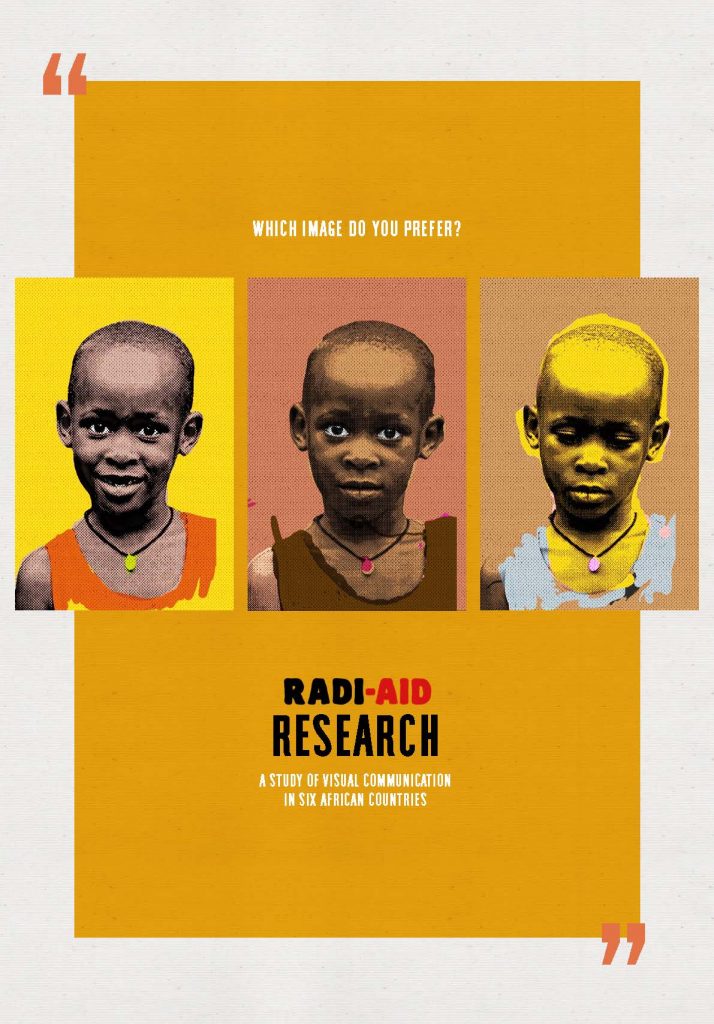

For instance, Adichie’s example of the single story of Africa might be represented by an image typically used by organisations seeking donations for development projects (see image below from Radi-Aid).

“The frequent portrayal of Africa as a continent in need prompted sadness among the respondents in the study, which was carried out in collaboration with the University of East Anglia (UEA) in the UK.

Such campaigns often depict black children in need, and several of the respondents wished that these stories could be complemented by showing children of other colors or backgrounds, or black doctors, professors or aid workers. They would like to see portrayals of people with agency in their own situations and results of their accomplishments.” — RADI-AID

Reflections on Teachers’ Responses, the Tool, and Issues of Power

Our comparative analysis found some differences, influenced partly by the way in which GCE has evolved in each country, as well as differing cultural, social, and political factors and histories. UK teachers were more likely to have encountered Adichie’s talk and were more familiar with the enquiry-based and participatory activities used in webinars. This reflects the influence of critical and postcolonial discourses towards a more critical form of GCE in the UK (Bullivant, 2020). In contrast, Italian teachers’ experience has been grounded primarily in intercultural education (Franch, 2020). Whilst topical events and issues unique to each country shaped the kinds of single stories shared by teachers to some extent, these were often part of over-arching themes common to both contexts. For example, discussions of single stories in the Brexit debate in the UK overlapped with themes of identity, migration, and populism in Italy. Beyond this, a number of other common themes emerged:

- Teachers in both contexts welcomed the space to share and reflect on complex issues, and experiment with the tool. They shared ideas about how they might use the tool in practice, including adaptations for different age groups.

- The concept of single stories resonated with teachers’ experiences personally and in their teaching with young people. They reflected on the responsibility of schools and available resources in perpetuating the ‘single story of progress’ about “developed” and “underdeveloped” countries (Andreotti, 2015).

- When reflecting on their own identities and the way in which single stories originate and persist, many teachers tended to remain at the level of superficial analysis of factors shaping identity and perceptions of self and others, rather than more critical analysis of the roots and power dynamics influencing these.

These themes support our rationale for developing the tool in the first place, especially the resonance found between the concept of single stories and teachers’ experiences and reflections on the inadequacy of existing resources to challenge these. They also informed ideas for developing it going forward. These include straightforward adaptations to terminology to create versions for different age groups and the more complex need to draw teachers’ attention to their own positions and perspectives, and questions of power underpinning these.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Dr Andrea Bullivant

Dr Andrea Bullivant is employed by Liverpool World Centre and has facilitated Global Citizenship Education for twelve years. Her work has focused increasingly on bringing research and practice together to develop new understanding across the sector, to engage community partners and develop evaluation and research that can support practice outcomes and influence policy. She is the Director of TEESNet, a UK wide network promoting GCE and Education for Sustainable Development in Teacher Education. She currently co-chairs Our Shared World and is the lead evaluator for a number of UK based GCE projects.

Dr Sarah Franch

Dr Sara Franch is an expert in international development cooperation and global citizenship education. She holds a PhD in pedagogy from the Free University of Bolzano and is involved in research and training on global citizenship. She currently works for a publisher and is responsible for developing products on pedagogical innovation.

GENE Awards

EERA is delighted and honoured to be partnering with the Global Educational Network in Europe (GENE) to make significant research funds available to our members to further research in the area of global education.

These research awards are funded by Global Education Network Europe (GENE), the European network of Ministries and Agencies with national responsibility for policymaking, funding, and support in the field of Global Education. For this reason, the subject area for research projects undertaken is that of Global Education.

The purpose of the award is to support quality research around the themes outlined here – which have been identified as of interest to policymakers. Gathering of existing research, application of existing research from other areas of education to Global Education, follow-up studies, all are perfectly acceptable. It is not expected that the research has to draw policy conclusions – but to make available up-to-date, policy-relevant research from which policymaker can draw their own conclusions.

References and Further Reading

Andreotti, V. 2006 Soft versus Critical Global Citizenship Education. Policy and Practice – A Development Education Review. Centre for Global Education https://www.developmenteducationreview.com/issue/issue-3/soft-versus-critical-global-citizenship-education

Andreotti, V. 2010 Postcolonial and post-critical ‘global citizenship education’. In G. Elliott, C. Fourali & S. Issler (Eds.), Education and Social Change: Connecting Local and Global Perspectives (pp. 238-250). London: Continuum. https://www.routledge.com/Postcolonial-Perspectives-on-Global-Citizenship-Education/Andreotti-Souza/p/book/9781138788060

Andreotti, V. 2015 Global citizenship education otherwise: Pedagogical and theoretical insights. In A. Abdi, L. Schultz & T. Pillay (Eds.), Decolonizing Global Citizenship Education (pp. 221- 230). Rotterdam: Sense Publishers. https://link.springer.com/chapter/10.1007/978-94-6300-277-6_18

Blackmore, C. (2014) The Opportunities and Challenges for a Critical Global Citizenship Education in One English Secondary School. Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Bath, Department of Education. April 2014 https://researchportal.bath.ac.uk/en/studentTheses/the-opportunities-and-challenges-for-a-critical-global-citizenshi

Bullivant, A., Ayre, J., and Smith, A. Facilitating the ‘Tipping Point’: Co-creating a manifesto for education for environmental sustainability. British Educational Research Association. Research Intelligence, Issue 150, Spring 2022 https://www.bera.ac.uk/publication/spring-2022

Bullivant, A. 2020. From Development Education to Global Learning: Exploring conceptualisations of theory and practice amongst practitioners in England. PhD Thesis. Lancaster University http://www.research.lancs.ac.uk/portal/en/publications/from-development-education-to-global-learning(9202418c-5116-425e-b0eb-40af09e3cc08).html

Franch, S. 2020 Global citizenship education discourses in a province in northern Italy. International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning. Vol. 12(1):21-36. https://www.scienceopen.com/hosted-document?doi=10.14324/IJDEGL.12.1.03

Pashby, K and Sund, L. Critical GCE in the Era of SDG 4.7: Discussing HEADS UP with Secondary Teachers in England, Finland and Sweden. In Bourn, D (ed). (2020) The Bloomsbury Handbook of Global Education and Learning. Bloomsbury https://www.bloomsburycollections.com/book/the-bloomsbury-handbook-of-global-education-and-learning/ch23-critical-global-citizenship-education-in-the-era-of-sdg-4-7-discussing-headsup-with-secondary-teachers-in-england-finland-and-sweden