Equity in Education during COVID-19 and the Danger of “Microwave Equity”

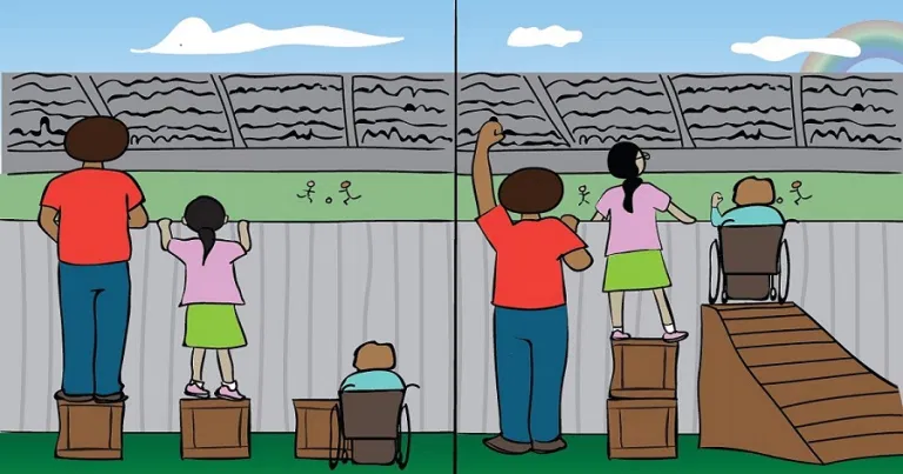

What is the difference between equality and equity?

The image to the left is a graphical representation of equality, while the image to the right represents equity

Image credit: Maryam Abdul-Kareem

It is quite challenging to unpack the concepts of equality and equity in education, particularly the differences between these two concepts. It is critical for teachers to know the differences between these two concepts to ensure equitable learning for all students, especially in a time of crisis.

In the left image, everyone is provided with equal support to watch the football game. In the right image, everyone is equipped with differential supports that allow equitable access to the game.

It should be noted that understanding the differences between equity and equality is not straightforward. It is layered with many complexities. Therefore, the above image provides a basic representation of the differences between equity and equality.

In summary, equity is based on needs, that is, responding to students’ individual or specific needs in our classrooms to ensure quality teaching and learning. In contrast, equality is based on fairness, which means being fair to all, without acknowledging the additional challenges faced by some.

UN Sustainability Goals and

the importance of equity and inclusion in education

The role of teachers in addressing equity and inclusion in their classrooms

Avoiding the quick fix of ‘Microwave Equity’

Image credit: Twitter user Valentina Gonzales Cornelius Minor Twitter

Cornelius Minor, a US-based educator, coined the term ‘Microwave Equity,’ which means teachers and educators attempting to achieve equity quickly or overnight. Instead, he warns, the work on equity in education takes time and patience. In his book, We Got This, Minor argued that to be equitable and inclusive, teachers need to intentionally listen to kids in achieving equity in the classroom, decentralise power by empowering students’ voices, and do the self-work without blaming students.

The push to introduce more equity in education is badly needed, but it comes at a time when teachers are already facing significant challenges and additional responsibilities due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Equity and the challenges of the COVID-19 pandemic

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Seun B. Adebayo

PhD Researcher, Research Supervisor, Teaching Assistant, NUI Galway

Seun B. Adebayo is currently a PhD Researcher, Research Supervisor and Teaching Assistant at the School of Education, National University of Ireland Galway, Ireland (NUI Galway). His PhD study explores developing culturally inclusive teaching and learning environments in Irish schools.

Aside from his research study, Seun organises workshops on culturally responsive pedagogies for student-teachers at NUI Galway.

His research interests include education policy, teacher education and professional development, culturally responsive pedagogy, equity and inclusion in education, progressive education reforms, practitioner/action research, education in conflict/post-conflict contexts, and quality education.

Seun has extensive work and research experiences with Aflatoun International, UNESCO HQ., UNESCO Office in Monrovia (Liberia), the European Research Council Executive Agency of the European Commission, the UNICEF Office of Research-Innocenti, VSO International, Inter-agency Network for Education in Emergencies (INEE), Education Development Trust and UNDP in New York.

ResearchGate: https://www.researchgate.net/profile/Seun-Adebayo

Twitter: https://twitter.com/Royalseun

Google Scholar: https://scholar.google.co.uk/citations?user=anOwtUQAAAAJ&hl=en

References and Further Reading

[1] UNESCO (2021). Education: From disruption to recovery. https://en.unesco.org/covid19/educationresponse

[2] Global Education Evidence Advisory Panel (2022). Prioritizing learning during COVID-19. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/114361643124941686/pdf/Recommendations-of-the-Global-Education-Evidence-Advisory-Panel.pdf

[3] Waterford (2020). Why Understanding Equity vs Equality in Schools Can Help You Create an Inclusive Classroom. https://www.waterford.org/education/equity-vs-equality-in-education

[4] Giardina (2019). What does an inclusive classroom look like? https://inclusiveschools.org/what-does-an-inclusive-classroom-look-like/

[5] https://sdg4education2030.org/the-goal

[6] UNESCO (2020). Inclusion and education: ALL MEANS ALL. Global Education Monitoring Report. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/in/documentViewer.xhtml?v=2.1.196&id=p::usmarcdef_0000373718&file=/in/rest/annotationSVC/DownloadWatermarkedAttachment/attach_import_d3682741-8fe5-4012-98c6-66d2bb13b7f0%3F_%3D373718eng.pdf&locale=en&multi=true&ark=/ark:/48223/pf0000373718/PDF/373718eng.pdf#p29

[7] Shulla, K. (2021). The COVID-19 pandemic and the achievement of the SDGs. https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s43621-021-00026-x

[8] Adebayo and Chinhanu (2020). Ubuntu in Education: Towards equitable teaching and learning for all in the era of SDG 4. NORRAG. https://www.norrag.org/ubuntu-in-education-towards-equitable-teaching-and-learning-for-all-in-the-era-of-sdg-4-by-chiedza-a-chinhanu-and-seun-b-adebayo/

[9] Moss and Bradley (2021). Education in a Post-COVID World: Creating more Resilient Education Systems. https://blog.eera-ecer.de/resilient-education/

[10] Adebayo S.B. (2019). Emerging perspectives of teacher agency in a post-conflict setting: The case of Liberia. Teaching and Teacher Education. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0742051X18300143?via%3Dihub

[11]Tao, S. (2013). Why are teachers absent? Utilising the Capability Approach and Critical Realism to explain teacher performance in Tanzania. International Journal of Educational Development, 33 (1): 2-14 https://www.researchgate.net/publication/257243592_Why_are_teachers_absent_Utilising_the_Capability_Approach_and_Critical_Realism_to_explain_teacher_performance_in_Tanzania

[12]Beauchamp, G., Hulme, M., Clarke, L., Hamilton, L., & Harvey, J. A. (2021). ‘People miss people’: A study of school leadership and management in the four nations of the United Kingdom in the early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic. Educational Management Administration & Leadership, 49(3), 375-392. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/1741143220987841