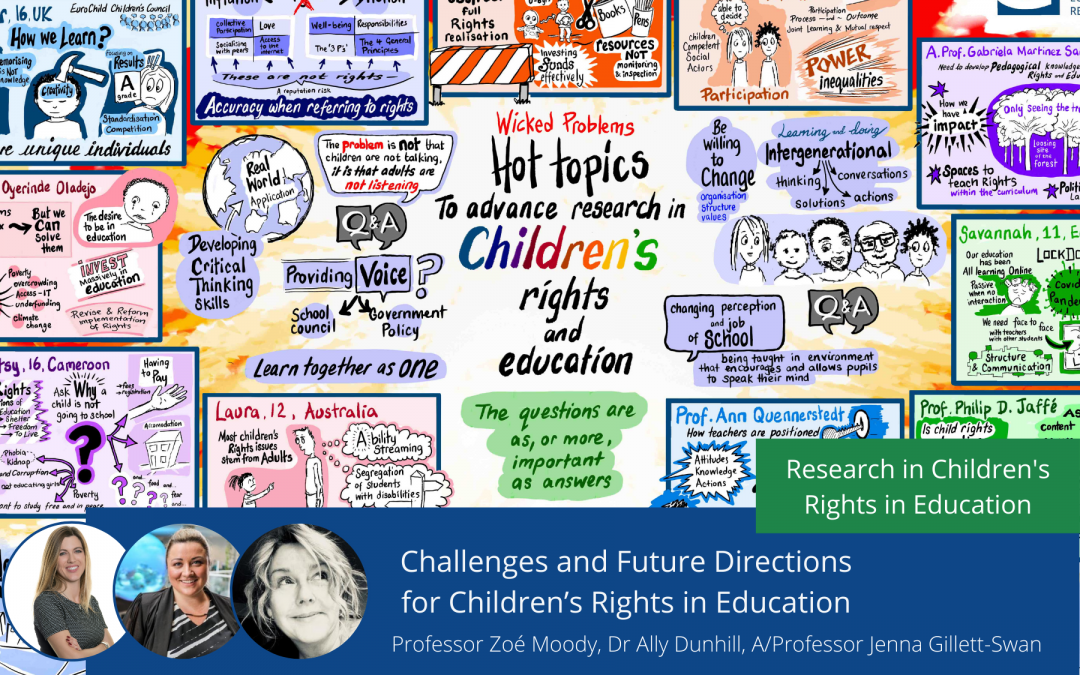

Why we must listen to migrant children: School belonging in a hostile environment

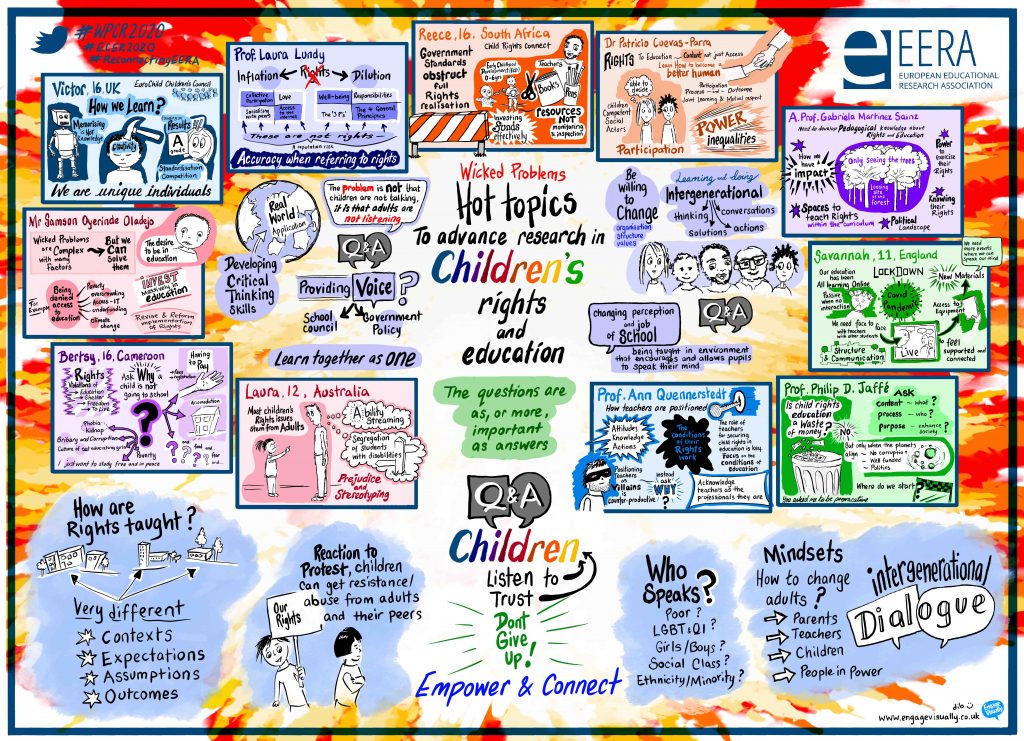

It seemed like a regular school room, with colourful posters on the walls, a small table with pencils and books, and two blue chairs tucked behind a large desk – but for hydrous [1], a 9-year-old boy from Poland, it meant belonging. It was a space where he felt secure, where he could get help with his English, and where staff showed him care and attention that made him feel seen. In a world that often felt confusing and unwelcoming, this room became a quiet anchor, a place where he could just be a child, not “the foreign kid”.

My research showed that schools can act as powerful spaces of inclusion and belonging for migrant children – what I describe as an oasis within wider hostile political environments. In a time when migration and diversity are increasingly politicised, recognising and supporting these inclusive spaces is more urgent than ever.

Image by hydrous

A hostile environment

Image by Luna

Across the UK and Europe, migration is being framed as a problem. From intensified border controls in Germany to stricter citizenship requirements in Italy through securitised language and policy in the UK, the environment has become deeply challenging for migrants, refugees, asylum-seekers, and their families. Anti-immigration rhetoric is no longer confined to the far right; even centrist and liberal parties have adopted exclusionary discourses and policies in an effort to appeal to nationalist sentiments.

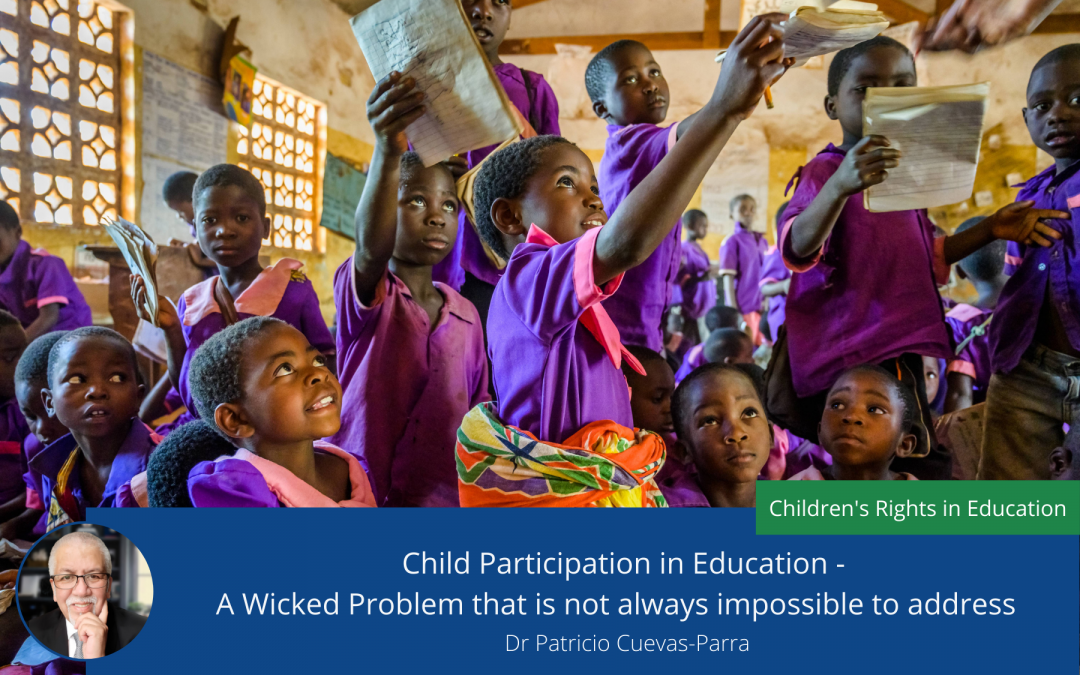

Children are not immune to these dynamics. Migrant children, in particular, are caught in the tensions between their lived experiences and the public narratives about who belongs and who doesn’t (Richey, 2023). While politicians and media outlets often discuss migration in abstract terms, real children are navigating these social currents daily, in classrooms, in playgrounds, and in their journeys to and from school.

This development is especially significant given that, across the European Union, children with a migrant background represent a growing proportion of the population. While around 10% of the general EU population was born outside the EU, among children, the proportion with at least one foreign-born parent is closer to one in four. This generational shift underscores the growing importance of fostering belonging, inclusion, and identity in schools. As classrooms become increasingly diverse, education systems must adapt to ensure that all children, regardless of background, feel recognised, valued, and supported.

The role of schools

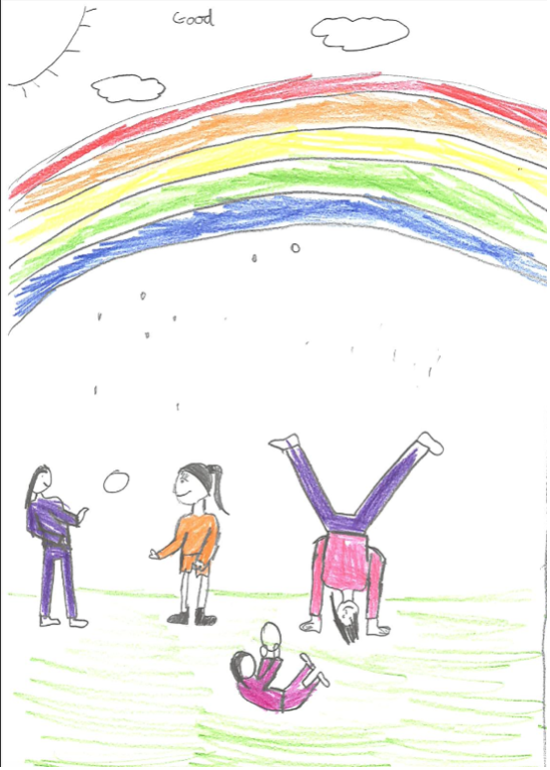

Children often talked about the importance of playing and being with friends

Drawing by Mistral

In this context, the role of schools becomes critical. For children, schools sit at the intersection of family and society and are often the first space where migrant children socialise with members from outside their ethnic group. Educational institutions have the potential to buffer against hostile discourses by fostering empathy, inclusion, and intercultural understanding, offering opportunities for children to anchor their belonging in formal, social, emotional and symbolic dimensions (Popyk, 2023). Multi-ethnic school environments, in particular, allow migrant children to experience their backgrounds as ordinary (Tajic and Lund, 2023), rather than exceptional.

My PhD thesis explored how children with a migrant background in post-Brexit England perceived their school environment. Conducted at a multi-ethnic primary school about 30 miles from London, the ethnographic study involved 15 Polish children aged 9–11, using participant observation and creative, child-centred methods, including drawings, photo voice, and Persona Dolls. It revealed that while broader society was increasingly hostile to immigrants, schools can provide safe, inclusive spaces that nurture children’s sense of belonging and support their identity development.

Through my research, I found that children place deep value on small, everyday gestures that acknowledge and respect their cultural backgrounds – whether it’s a teacher learning a few words in their native language or seeing their national flags proudly displayed on classroom walls and learning materials. The children praised the school’s ethos of inclusivity and identified racism as something more commonly encountered in other educational settings. They also spoke about the importance of friendship as a way to counter hostility and discrimination. Of course, not all schools succeed in creating such environments, and some can even reproduce marginalisation and inequalities (Tereschenko et al., 2019), but my research highlights how, in some cases, schools can provide much-needed spaces of safety, recognition, and support.

The missing voices of children

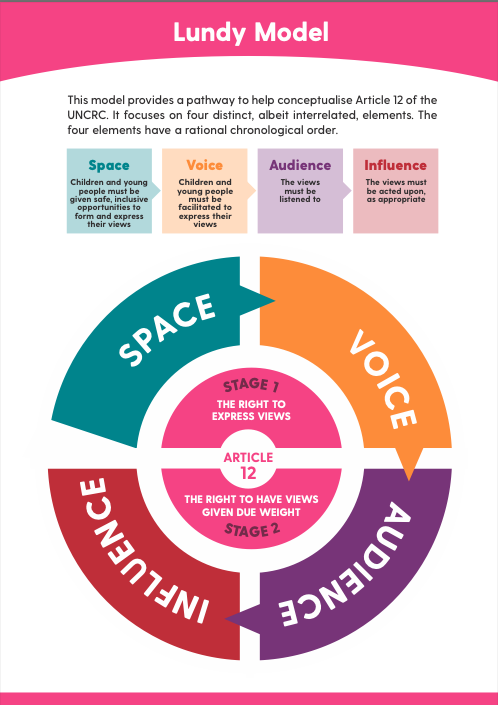

What is often missing from public debates is the perspective of migrant children themselves. We talk about them but rarely listen to them. And yet, their insights are vital, not only for creating inclusive school environments but also for informing broader conversations on migration, education, and children’s rights. Schools, as everyday sites of encounter and negotiation, offer valuable lessons for society on how to foster tolerance, challenge xenophobia, and better understand the lived realities of migration.

Final thoughts

Schools can serve as spaces of belonging in the context of increasingly exclusionary politics, offering migrant children recognition and inclusion. To strengthen this role, further research is needed on how education systems can meaningfully engage with and reflect migrant children’s voices, ensuring their experiences inform policies and practices.

Key Messages

- Migration has become increasingly politicised across Europe, with anti-immigration attitudes, discourses, and policies creating a hostile environment for migrant children.

- Schools can act as buffers of resistance, fostering belonging through inclusive pedagogies and practices.

- Listening to migrant children’s voices is essential for shaping inclusive education policies and practices. Their perspectives can inform wider efforts to build more tolerant and cohesive societies.

Dr Thi Bogossian

University of Warwick, UK

Thi Bogossian (they/them) recently completed a PhD in Sociology at the University of Surrey (UK) and is currently based at the University of Warwick. With research interests in childhood and youth, education, migration, and gender, they bring previous experience as a school teacher and are now building a research and teaching profile in higher education.

Thi is actively engaged in international and comparative research and has contributed to global policy initiatives in the field of education

Other blog posts on similar topics:

[1] I gave children the opportunity to choose their pseudonyms. In the assent form, hydrous did not capitalise his name and I decided to respect his decision.

Bogossian, T. (2024). Polish schoolchildren in post-Brexit England: Performativities, identities, and sense of belonging. [PhD]. University of Surrey. DOI: 10.15126/thesis.901242

Eurostat, Statistics Explained. (2025) EU population diversity by citizenship and country of birth. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=EU_population_diversity_by_citizenship_and_country_of_birth. Accessed on 05-Aug-2025.

Gaál, F. (2025). Germany ramps up border checks. Deutsche Welle. https://www.dw.com/en/tighter-borders-germany-ramps-up-checks/video-72606467. Accessed on 05-Aug-2025.

Moench, M. (2025). Italy tightens rules for Italian descendants to become citizens. BBC News. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cdxkk0z9y05o. Accessed on 05-Aug-2025.

Orav, A. (2023). Integration of migrant children. [Briefing]. European Parliamentary ResearchService. PE754.601. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/BRIE/2023/754601/EPRS_BRI(2023)754601_EN.pdf. Accessed on 05-Aug-2025.

Popyk, A. (2022). Anchors and thresholds in the formation of a transnational sense of belonging of migrant children in Poland. Children’s Geographies, 21(3), 459–472. DOI: 10.1080/14733285.2022.2075693

Richey, S. (2023). Collateral Damage: The Influence of Political Rhetoric on the Incorporation of Second-Generation Americans. University of Michigan Press. https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.3998/mpub.11691056

Syal, R. (2025). Starmer accused of echoing far right with ‘island of strangers’ speech. The Guardian. https://www.theguardian.com/politics/2025/may/12/keir-starmer-defends-plans-to-curb-net-migration. Accessed on 05-Aug-2025.

Tajic, D., Lund, A. (2023). The call of ordinariness: peer interaction and superdiversity within the civil sphere. American Journal of Cultural Sociology 11, 337–364. DOI: 10.1057/s41290-022-00154-5

Tereshchenko, A., Bradbury, A., & Archer, L. (2019). Eastern European migrants’ experiences of racism in English schools: positions of marginal whiteness and linguistic otherness. Whiteness and Education, 4(1), 53–71. DOI: 10.1080/23793406.2019.1584048