Easy and difficult maths problems – and why language matters

As soon as we receive a task, we judge it, whether mentally or verbally. Is it interesting, boring, easy, difficult, or worthwhile? In school, teachers and students handle a large number of tasks every day, so it is unsurprising that they do the same.

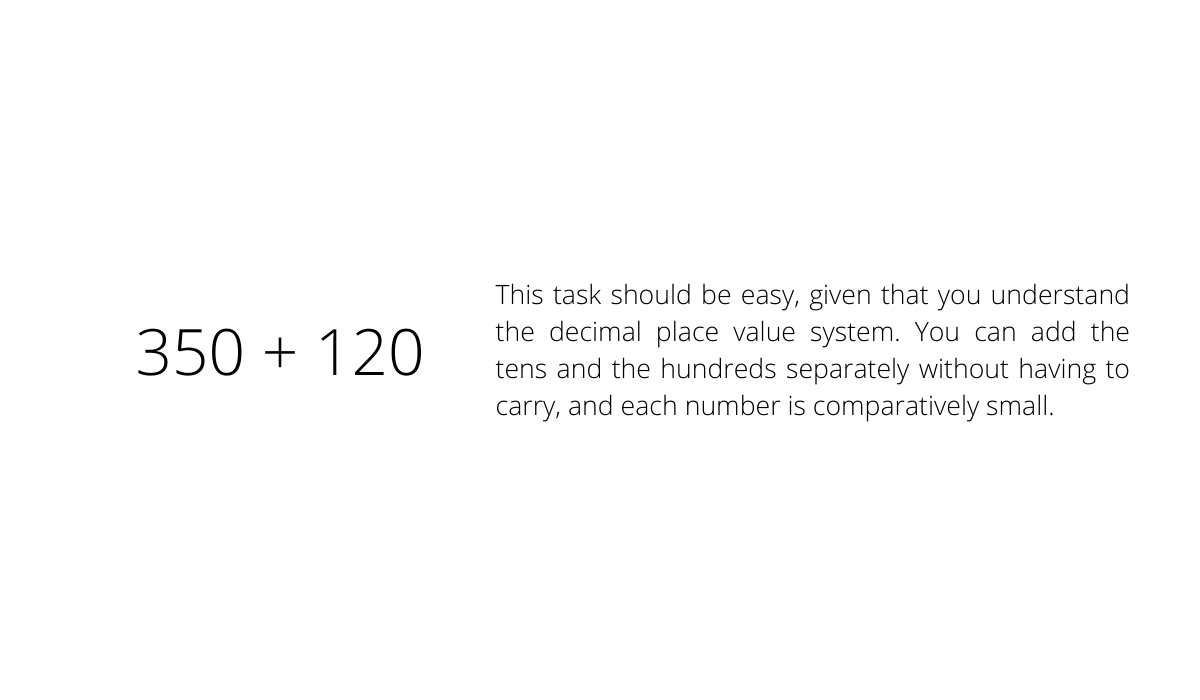

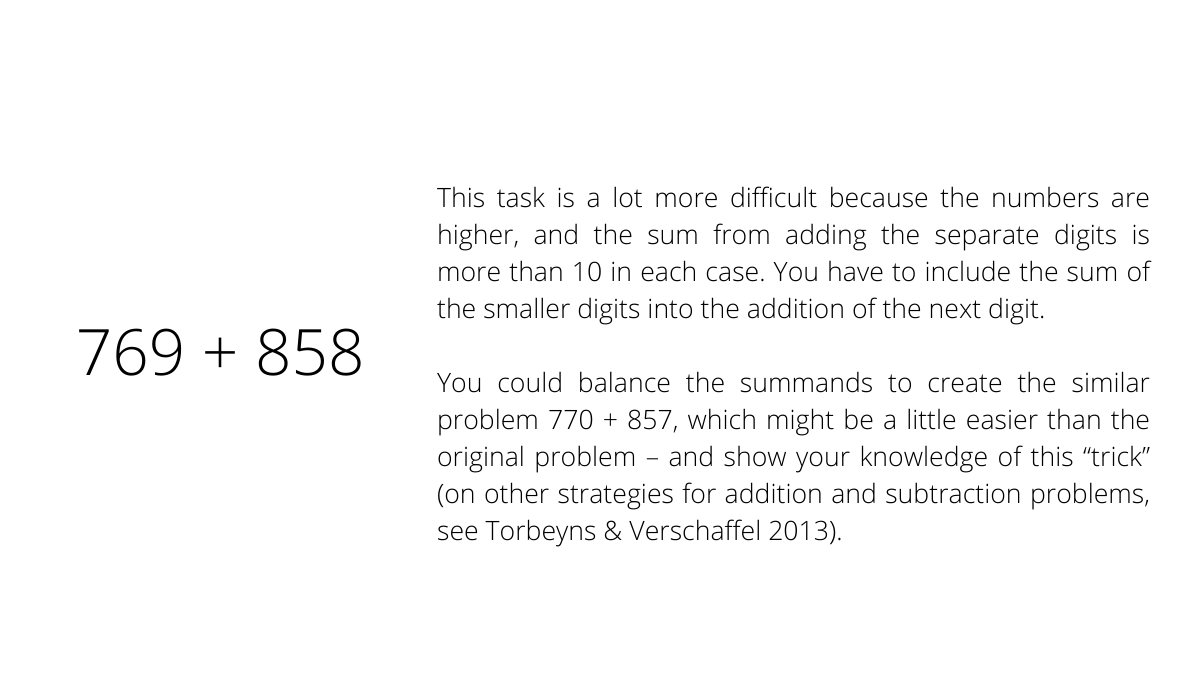

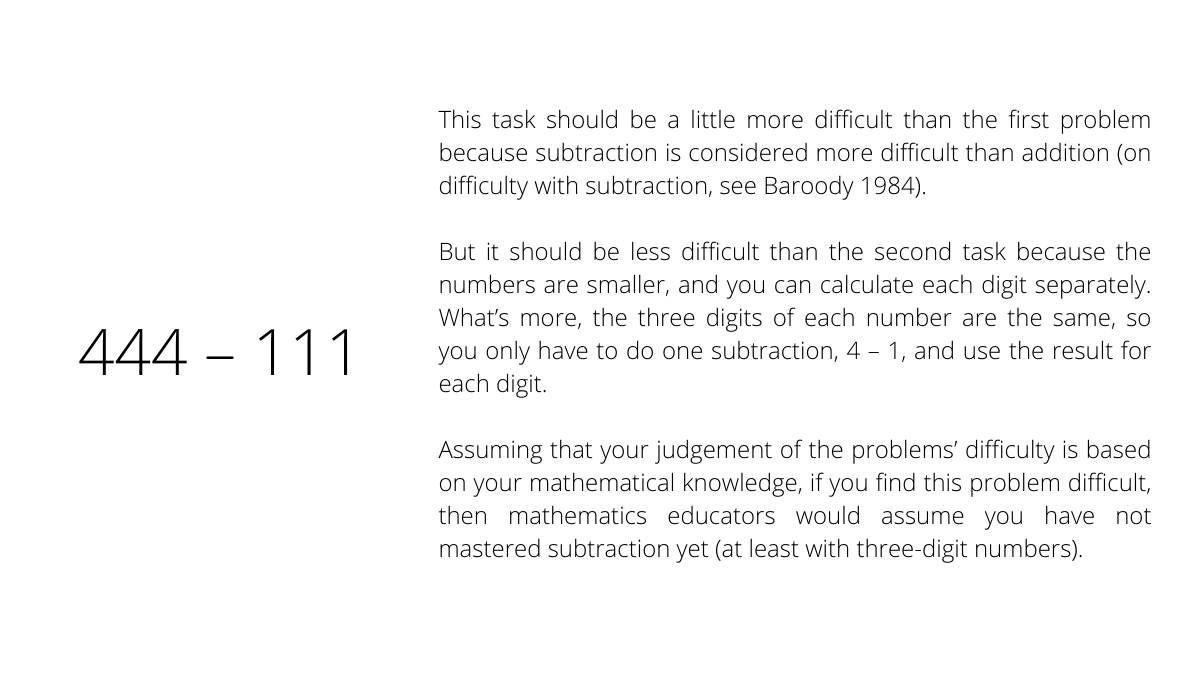

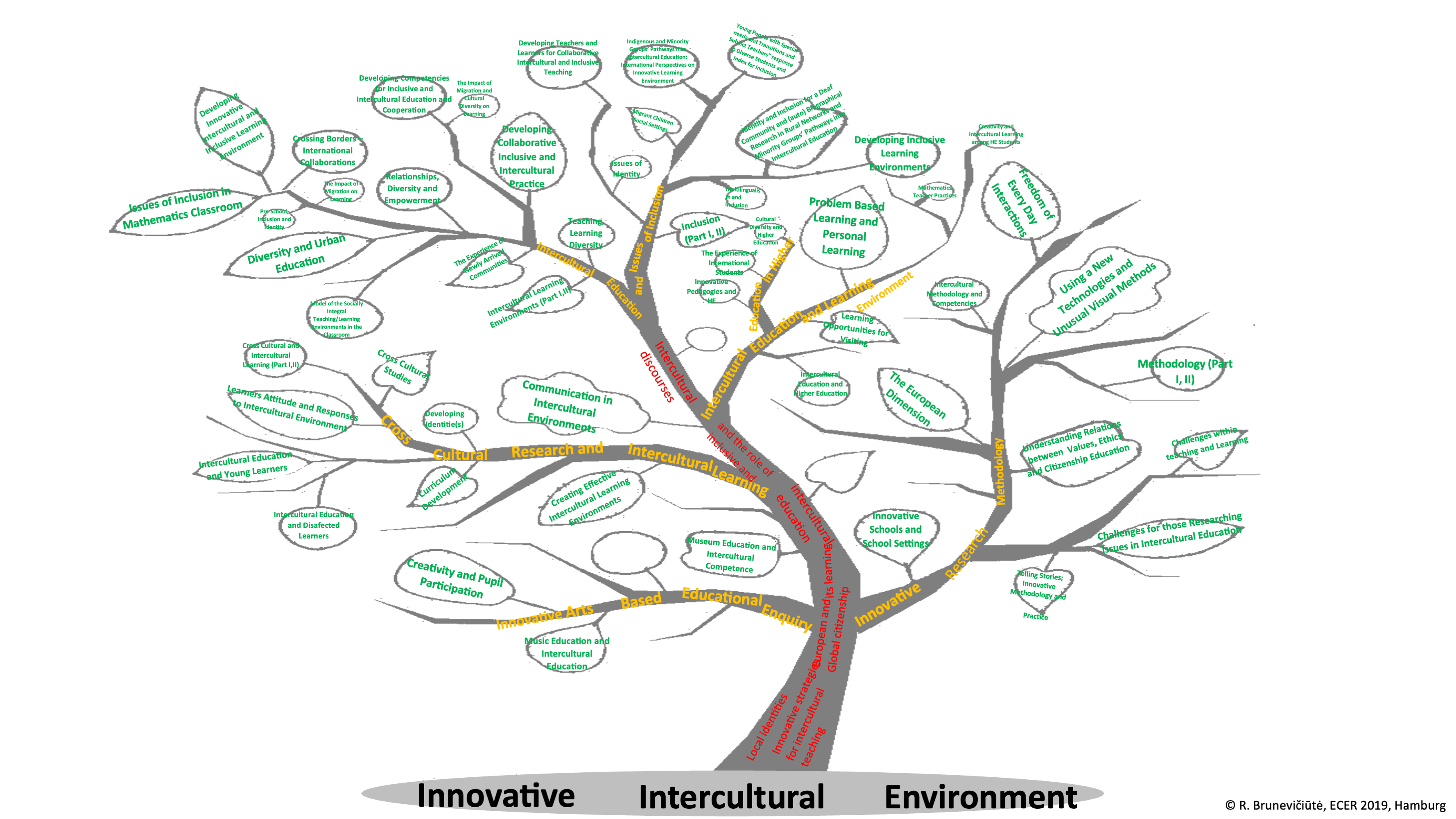

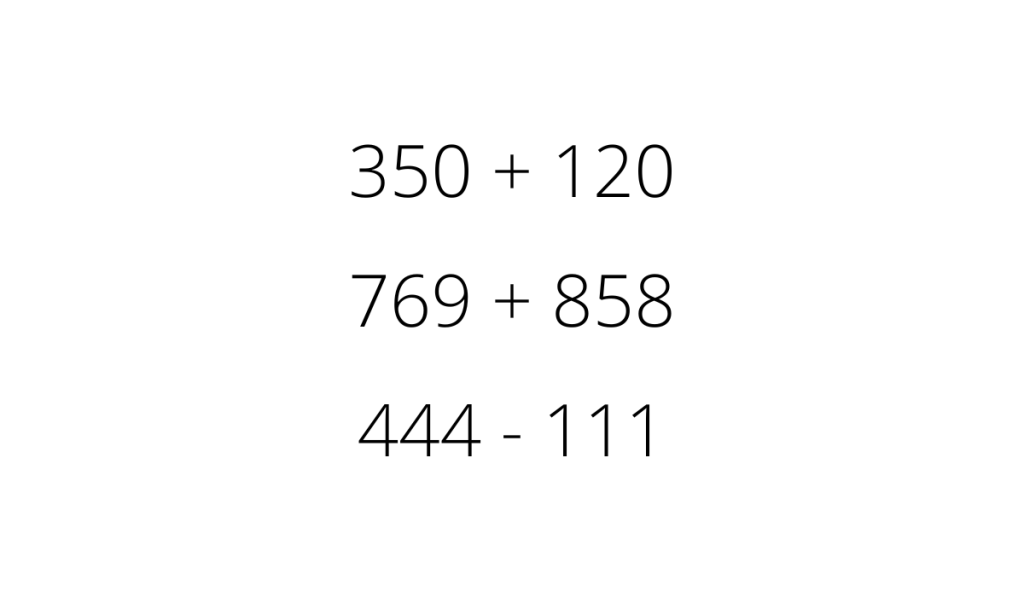

For example, when looking at the maths problems below, can you immediately tell which ones you find easy and which you would find more difficult to solve?

If you were then asked to sort each addition problem according to its difficulty into the following table, could you solve the task, or would you hesitate?

This sorting task is commonly used in German primary schools. Let’s take a closer look at it, and at the linguistic level of its illustrations. At first glance, the teacher may think this is a simple task, but when considered more closely, it is clear that understanding the task depends on the level of students’ experience, especially those new to the language of instruction, i.e., non-native speakers.

In this blog post, I’d like to expand on the situational and linguistic factors that influence how a student may perceive the difficulty of a maths problem – beyond their basic mathematical abilities.

Are there objective or subjective categories in mathematics teaching?

According to mathematics educators, the difficulty of math problems depends on how much effort students have to put into solving each problem, which again depends on their mathematical abilities (Rathgeb-Schnierer & Green 2015), and even diagnoses such as dyscalculia and other learning disabilities.

With this in mind, let’s look again at the maths problems above, how students might perceive them, and how educators might react to students who struggled with the task. Did you find them easy or difficult to solve?

References in the illustration: Torbeyns&Verschaffel (2013), Baroody (1984),

Situational factors that affect mathematics understanding

Your judgement of a task’s difficulty might also depend on other factors. Maybe you spent the last weeks working only on subtraction problems, so they seem a little easier right now. Maybe your favourite number is eight, so you enjoy calculating with numbers that contain an eight, which makes the second problem the easiest for you. Perhaps the person next to you received the worksheet earlier, and after watching them calculate, none of the problems are difficult for you anymore. Maybe you want to impress your teacher by showing that you can solve all of the problems, even though they are difficult.

Your mathematical knowledge and familiarity with certain calculation strategies is only one factor that might affect how you solve maths problems. Equally important is your current situation and your relationship with the people you solve the problems with and for.

Whether you use the table to sort the problems as expected also depends on whether the task and the symbols were explained properly.

Linguistic factors that affect mathematics understanding

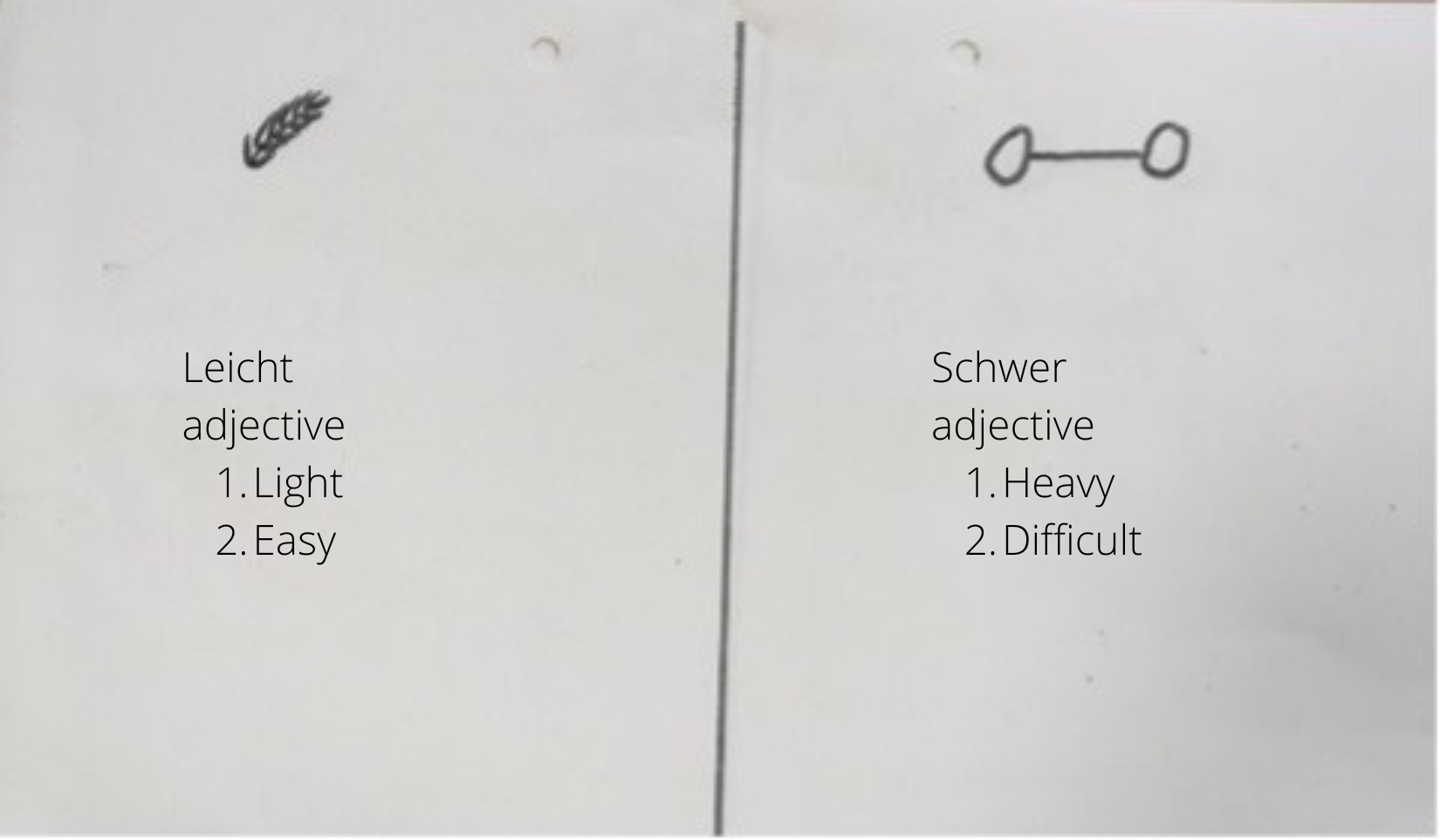

Whether the table above left you at a loss probably depends on how familiar you are with the German translations of ‘easy’ and ‘difficult’: ‘Leicht’ and ‘schwer’.

These words are often illustrated using drawings in the picture above of a feather and a dumbbell. These symbols are based on a second meaning of the German terms. ‘Leicht’ can also mean ‘light’ in the sense of weight, as illustrated by the feather. ‘Schwer’ can mean ‘heavy’, as illustrated by a dumbbell.

The task is to put the problems you find easy in the left column with the feather and the problems you find difficult in the right column with the dumbbell.

This example of a task observed in a German primary school classroom shows the relevance of language in mathematics classes – and how unexpected it can sometimes be. Without the linguistic explanation, there is no way of logically concluding which column to use for the easy and which for the difficult problems. Trying to find a logical connection between the terms and the symbols might even be misleading.

For example, you might consider the difficulty of a task to be its complexity and apply this to the illustrations. In that case, you might find the dumbbell symbol (which only consists of three lines) a lot less complex than the feather symbol. Consequently, you would sort the easy and difficult problems opposite to the task’s intention. Your only chance to use the table as intended would be to guess. But if you guessed wrong (and you have a 50% chance to do so), that would not be indicative of either your linguistic or mathematical abilities.

Especially when working with a student who is new to the language of instruction, we teachers, teacher assistants, or peers may be quick to assume students’ mistakes are due to a lack of linguistic understanding. We might even believe they didn’t receive proper mathematics education in their previous school.

Conclusion

There is more than mathematics and mathematics learning going on in mathematics lessons. We are often not aware of linguistic aspects, even in tasks and phrases we use every day, that are not explained sufficiently, even by translating.

All students face the challenge of handling these linguistic and situational aspects, but they may be especially confusing to those who have only recently joined a class in a new country, a new language, or a new culture.

Can you think of an example of ambiguous terms or tasks in your native language? Do you also use the differentiation between ‘easy’ and ‘difficult’ maths problems in your schools?

Key Messages

- Beyond the actual learning of mathematics, situational and linguistic aspects are relevant when students are working on a task

- Any of these aspects can influence whether a maths problem is perceived by the student as easy or difficult. Not understanding the maths problem, therefore, does not unambiguously point to a level of mathematical ability

- Certain aspects of language can be open to interpretation, such as when using images. We need to be aware of this and take more care when using everyday tasks and phrases that might cause confusion.

Alexandra Dannenberg

Research Assistant and PhD candidate, Kassel University, Germany

Alexandra Dannenberg is currently a research assistant and PhD candidate at Kassel University, Germany, and the graduate school InterFach. She studied primary education in the subjects mathematics, German as a first language, and natural & social sciences. During her studies, she discovered her interest in education research and began her current position in primary education research shortly after graduating. In her doctoral studies, she focuses on the relevance of language in primary school mathematics classroom interactions. Her general research interests are power relations in education, educational disparities, and institutional discrimination.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Baroody (1984): Children’s Difficulties in Subtraction: Some Causes and Cures. In: The Arithmetic Teacher, 32, 3, pp. 14-19. https://www.jstor.org/stable/748349?seq=1&cid=pdf-reference#references_tab_contents

Rathgeb-Schnierer & Green (2015): Cognitive flexibility and reasoning patterns in American and German elementary students when sorting addition and subtraction problems. In: Proceedings of CERME 9 – Ninth Congress of the European Society for Research in Mathematics Education, pp. 339-345. https://hal.science/hal-01281858/document

Torbeyns&Verschaffel (2013): Efficient and flexible strategy use on multidigit sums: a choice/no-choice study. In: Research in Mathematics Education, 15, 2, pp. 129-140. https://doi.org/10.1080/14794802.2013.797745