Procrastination, teachers, and posthuman theories – when social media and educational research collide

The use of social media by teachers and education researchers is a topic that generates a lot of debate – much of it, ironically, on social media. Jo Albin-Clark found unexpected benefits from using Twitter and agreed to share these with us.

If you’d like to join in the discussion on Twitter, here’s where to find the EERA twitter account and Jo on Twitter.

Procrastinating with Twitter

Twitter is a gift to the procrastinating researcher. As anyone with a writing deadline will attest, you get very creative. At times I can write fluently, collaborate with ease and produce abstract after abstract. But other times, I can find so many reasons not to write.

The ultimate procrastination tool nestles in the palm of my hand. Twitter is the gift that keeps on giving. Discovering other people’s research, snorting at funny memes, and networking with like-minded souls has brought fresh collaborations (Albin-Clark et al., 2021). Twitter has me hook, line and sinker, and it can stall my writing plans if I let it. But what I had not expected was how Twitter would become a means to write. I didn’t see that coming.

Researching with Twitter

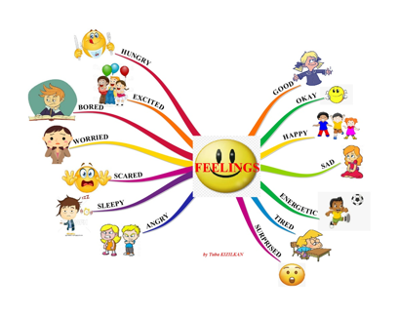

As a teacher of young children and now a university-based researcher of documentation practices, I started to notice how my subject manifested through Twitter. I’m interested in teachers’ documentation practices, where photography, video and/or written narration capture playful learning (Albin-Clark, 2021).

I’ve found posthuman and feminist materialism theories happy bedfellows for researching documentation. Through this, you can imagine the rich, dynamic entanglements afoot (Strom et al. 2020 p 2). Documentation is re-imagined as lively and agentic matter (Lenz Taguchi, 2010; Elfström Pettersson, 2017; Merewether, 2018). When you start thinking about a non-human thing (like documentation) having an agency, teachers slip from the central focus. Such moves have enabled leaps from questions about the meanings of documentation to what documentation is doing (Albin-Clark, 2021).

Now I’ve started wondering about how teachers engage with Twitter and in what ways documentation can become a digital doing (Albin-Clark, 2022; Thompson, 2016).

Teachers using Twitter

Teachers are always looking for the new and have employed technology through digital documentation (Flewitt and Cowan, 2019; Flewitt and Clark, 2020). Mobile documentation is gaining in popularity, where mobile devices connect home and school (Lim and Cho, 2019). But once I started to pay attention, teachers were tweeting documentation all over the show.

Klinkenborg (2012 p.127) attests that; ‘Being a writer is an act of perpetual self-authorization’.

So, it seems I can combine procrastination with research practice!

Twitter and documentation of children’s learning

Most days, Michelle, the teacher I researched with, put documentation to work. It adorned classroom walls; shared endlessly with children’s families. Charged and troubled planning-assessment cycles (Albin-Clark, 2019). What got me thinking was a tweet Michelle made called ‘Rainbow Spaghetti’. It told stories of exploratory play with unconventional materials. ECEC teachers have an eye for the unorthodox.

In the tweet, Michelle’s home kitchen countertop provides the setting, with cold, cooked, brightly coloured spaghetti sitting in bags. Counterposed with the day after, sociable little fingers lunge into an overspilling spaghetti-filled tray (Albin-Clark et al., 2021). Michelle explained how the hashtags came about (#readytowrite, #sensory play, #messy play). They gesture towards playful learning as instrumental to curricula progress and associated learning with active and sensory exploration.

If you notice the mobile documentation of Rainbow Spaghetti, the more-than-human comes into view. Bags of cold spaghetti on the kitchen top are timestamped and reveal evening time activity. Social media here becomes an additional labour; the personal and professional blur. As Michelle’s family kitchen becomes visible, vulnerabilities become observable in digital spaces (Stratigos and Fenech 2020).

Implications for tweeting teachers (and procrastinating researchers)

So, what were these tweets doing in the “digital-material-sensory-affective-spatial assemblage”? (Ringrose and Renold 2016, 238).

I have only just scratched the surface. But mobile documentation performs. For teachers, it blurs the boundaries between personal and professional subjectivities. Hidden labours lurk in liminalities, ethical tensions remain for children being documented and objectified in cultures of surveillance (Lindgren, 2012).

Further enquiries might investigate socially mediated multiplicities. Diverse and lively intra-actions abound in creating, sending, hashtagging, reading, liking, commenting, datafying and much more besides (Albin-Clark, 2022; Mertala, 2019).

Amongst the liveliness of timestamps and hashtags we glimpse more. Whole discourses vibrate with the phone’s materiality in teachers’ back pockets. And pedagogical tools present themselves (Luo and Xie 2019).

Now more than ever, teachers need to tell stories (Moss, 2015). Storytelling what is important could open fractures to resist dominant neo-liberal narratives (Moss and Roberts-Holmes, 2021; Archer and Albin-Clark, 2022). Twitter, therefore, offers accessible ways for teachers (and researchers) to swiftly operationalise digital doings that are hopeful, bite-size and accessible storytelling.

I am telling you; Twitter is where procrastination is at! It can be a productive space. So, use social media to connect to like-minded souls. You never know where it may take you.

Key Messages

- Social media is not just procrastination, with theories from posthumanism, they can bring interesting lenses for early childhood research practices.

- Social media offers accessible ways for teachers (and researchers) to swiftly operationalise digital doings that provide hopeful, bite-size and accessible storytelling.

- Documentation of young children’s learning in digital spaces brings ethical questions and recent platform changes may add further complications.

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Dr Jo Albin-Clark

Senior Lecturer Early Education

Dr. Jo Albin-Clark is a senior lecturer in early education at Edge Hill University. Following a teaching career in nursery and primary schools, Jo has undertaken a number of roles in teaching, advising and research in early childhood education. She completed a doctorate at the University of Sheffield in 2019 exploring documentation practices through posthuman and feminist materialist theories in early childhood education. Her research interests include observation and documentation practices and methodological collaboration and research creation through posthuman lenses. Throughout her work, teachers’ embodied experiences of resistances to dominant discourses has been a central thread.

https://orcid.org/0000-0002-6247-8363

https://research.edgehill.ac.uk/en/persons/joanne-albin-clark

References and Further Reading

Alasuutari, M., A. Markström, and A. Vallberg-Roth. 2014. Assessment and Documentation in Early Childhood Education. Abingdon: Routledge.

Albin-Clark, J. 2019. “What Forms of Material-Discursive Intra-Action are Generated through Documentation Practices in Early Childhood Education?” Educational Doctorate thesis, University of Sheffield.

Albin-Clark, J. 2020. “What is Documentation Doing? Early Childhood Education Teachers Shifting from and between the Meanings and Actions of Documentation Practices.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood: 1-16. doi:10.1177/1463949120917157

Albin-Clark, J., Latto, L., Hawxwell, L. and Ovington, J. (2021). ‘Becoming-with response-ability: How does diffracting posthuman ontologies with multi-modal sensory ethnography spark a multiplying femifesta/manifesta of noticing, attentiveness and doings in relation to mundane politics and more-than-human pedagogies of response-ability?’, entanglements, 4(1): 21-31 https://entanglementsjournal.org/becoming-with-response-ability/

Albin-Clark, J., 2022. What is mobile documentation doing through social media in early childhood education in-between the boundaries of a teacher’s personal and professional subjectivities?. Learning, Media and Technology, pp.1-16. https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/full/10.1080/17439884.2022.2074450

Archer, N., & Albin-Clark, J. (2022, Jul 7). Telling stories that need telling: A dialogue on resistance in early childhood education . (2 ed.) Lawrence Wishart. https://journals.lwbooks.co.uk/forum/vol-64-issue-2/abstract-9564/

Elfström Pettersson, K. 2017. “Teachers’ Actions and Children’s Interests. Quality Becomings in Preschool Documentation.” Tidsskrift for Nordisk Barnehageforskning 14 (2): 1-17. doi:10.7577/nbf.1756.

Flewitt, R. and K. Cowan. 2019. Valuing Signs of Learning: Observation and Digital Documentation of Play in Early Years Classrooms the Froebel Trust Final Research Report. Edinburgh: Froebel Trust.

Lenz Taguchi, H. 2010. Going Beyond the Theory, Practice Divide in Early Childhood Education. 1. publ. ed. London: Routledge.

Lim, S. and M. Cho. 2019. “Parents’ use of Mobile Documentation in a Reggio Emilia-Inspired School.” Early Childhood Education Journal 47 (4): 367-379. doi:10.1007/s10643-019-00945-5.

Lindgren, A. 2012. “Ethical Issues in Pedagogical Documentation: Representations of Children through Digital Technology.” International Journal of Early Childhood 44 (3): 327-340. 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2007.01517.x.

Luo, T. and Q. Xie. 2019. “Using Twitter as a Pedagogical Tool in Two Classrooms: A Comparative Case Study between an Education and a Communication Class.” Journal of Computing in Higher Education 31 (1): 81-104. doi:10.1007/s12528-018-9192-2.

Mertala, P. 2019. “Digital Technologies in Early Childhood Education – a Frame Analysis of Preservice Teachers’ Perceptions.” Early Child Development and Care 189 (8): 1228-1241. doi:10.1080/03004430.2017.1372756.

Merewether, J. 2018. “Listening to Young Children Outdoors with Pedagogical Documentation.” International Journal of Early Years Education 26 (3): 259-277. doi:10.1080/09669760.2017.1421525.

Moss, P. 2015. “Time for More Storytelling.” European Early Childhood Education Research Journal 23 (1): 1-4. doi:10.1080/1350293X.2014.991092.

Moss, P. and G. Roberts-Holmes. 2021. “Now is the Time! Confronting Neo-Liberalism in Early Childhood.” Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood: doi:10.1177/1463949121995917.

Ringrose, J. and E. Renold. 2016. “Cows, Cabins and Tweets: Posthuman Intra-Active Affect and Feminist Fire in Secondary School.” In Posthuman Research Practices in Education, edited by C. Taylor and C. Hughes, 220-241. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK. doi:10.1057/9781137453082_14.

Sparrman, A. and Lindgren, A. 2010. “Visual Documentation as a Normalizing Practice: A

New Discourse of Visibility in Preschool.” Surveillance & Society 7 (3/4): 248-261. 10.24908/ss.v7i3/4.4154

Stratigos, T. and M. Fenech. 2020. “Early Childhood Education and Care in the App Generation: Digital Documentation, Assessment for Learning and Parent Communication.” Australasian Journal of Early Childhood,46 (1): 1-13. doi:10.1177/1836939120979062.

Strom, K., J. Ringrose, J. Osgood, and E. Renold. 2020. “PhEmaterialism: Response-Able Research & Pedagogy.” Pedagogy . Reconceptualizing Educational Research Methodology, 10 (2-3): 1-39. https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/10091313.

Thompson, T. 2016. “Digital Doings: Curating Work-Learning Practices and Ecologies.” Learning, Media and Technology 41 (3): 480-500. doi:10.1080/17439884.2015.1064957.