Caring for Those who Teach Online – Reflections from a Virtual Staffroom

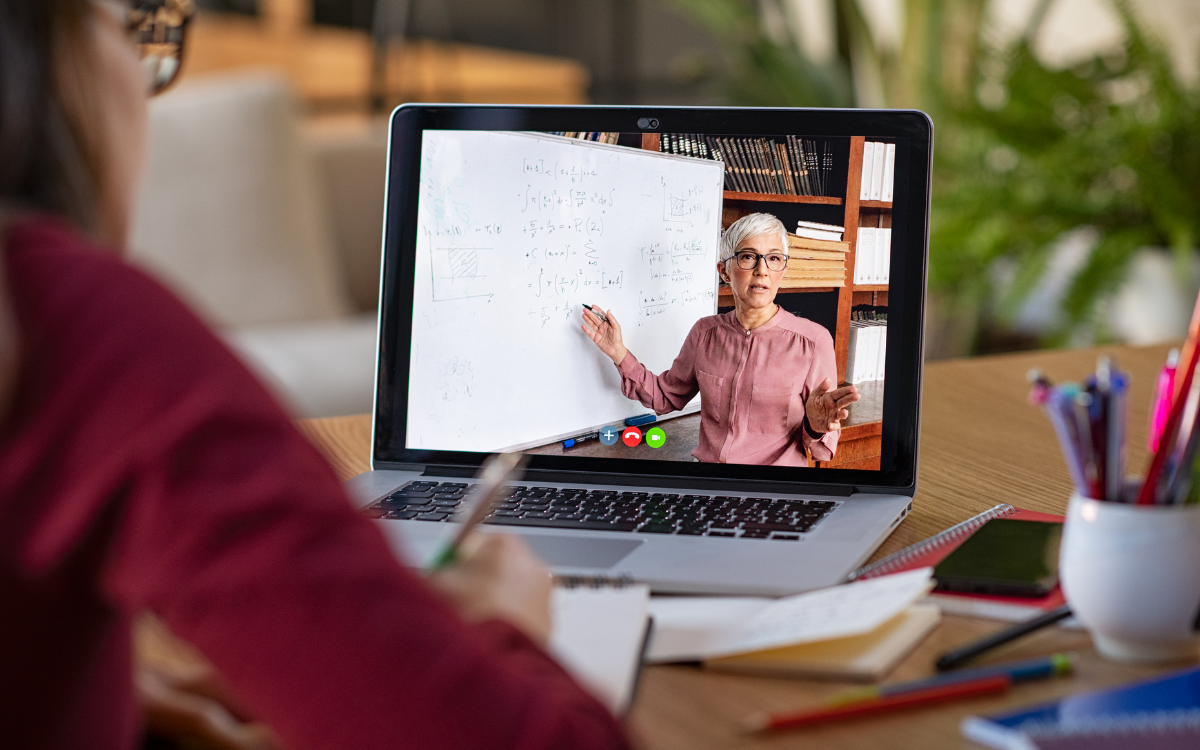

When schools and higher education institutions closed their doors in March 2020, some of the implicit and informal supports for teacher educators disappeared. As teacher educators migrated to new modes of teaching and learning, institutional supports such as IT upskilling, educational technologies, professional development, and assistance from HR were provided. However, many staff commented that the burden of the expectations placed on them often exceeded what they felt capable of responding to in a personal capacity. With this as the backdrop, I want to reflect on how staff in one institution developed more informal ways of supporting each other and building community in a time of isolation and fragmentation.

The imperative to create what Noddings calls ‘a climate in which caring relations can flourish’, and through which a sense of belonging can be maintained, led to us setting up a virtual staff room. The staff room doors opened for a coffee break from 11.00 to 12.00 every morning. To date, this has happened on over 120 occasions with more than 90 colleagues engaging in the staff room at different times. This casual drop-in space was hosted on Zoom with a reminder sent to all staff ten minutes before the room was opened. The live interaction was supported by emails, phone calls, and some shared photography and cooking projects.

As with any staff room, the tone was set by the people in the room at any given time. Ultimately what emerged was a supportive conversational space which broke down barriers as people swapped the small details and intimacies of everyday living and allowed colleagues glimpses into one another’s lives. This online space was characterised by a framework of CARE: a space for free-flowing conversation on a range of topics from the sublime to the ridiculous, attention to each other, deepening relationships with colleagues, and an increasing empathy as we observed something of each other’s homes and family lives. What we learned from the virtual staff room is that each element of this framework of CARE has to be supported by a number of integrated principles for practice: presence, production, performance, persona, personal, pastoral, and peer-to-peer.

Presence: Developing and maintaining a supportive space for conversation demands the fully engaged presence of the host in the virtual space. The host cannot dominate the conversation but will have to facilitate it. The continuity of having the same host, meeting at the same time, and sending a regular reminder, offered people a sense of assurance that some things stayed the same. As one colleague noted: ‘Just knowing that there are opportunities like this to connect goes a long way to help you feel more connected right away’.

Production: We learned that there should be no agenda or expectation of having to engage in quizzes or activities so that participants have the chance to ‘switch-off’ from having to do something. Participants wanted to ‘be’ with each other rather than to ‘do’.

Performance: Some personality types were comfortable adopting a virtual persona and spoke comfortably to the camera in the early stages of the virtual staff room, whereas it took others time to be comfortable in the space. Trying to ensure that all participants can be seen on one screen is vital for bringing quieter participants into the chat.

Persona: During the early weeks of meeting each other, there was a sense that participants were conscious of performing for the camera and projecting a positive persona. This mitigated against revealing what was really happening for them. Empathic conversations ensued when someone risked saying that things were not going so well for them.

Personal: The host has to ensure that people are introduced to each other as many colleagues may not have met in real-life. Deepening relationships in a CARE framework means that the virtual staffroom welcomed children, partners, and pets and provided glimpses of each other’s homes and gardens as part of caring for each other. In the words of one participant: ‘I like meeting people’s children and pets and seeing their homes and gardens – makes me feel more connected.’

Pastoral: Taking a CARE approach to hosting the virtual staff room will occasionally draw the host into providing pastoral support for some participants. CARE will sometimes call for actions that we might not have anticipated.

Peer-to-peer: CARE is ultimately a peer-to-peer activity based on the realisation, again in the words of a participant, ‘that we are in this together, I look forward to seeing the familiar faces.’ The virtual staff room extended people’s social network by creating new links and new modes of engagement between colleagues.

What began as an informal approach to caring for staff and keeping us connected with each other, the virtual staff room has become an example of how taking a CARE approach to an online space can provide a positive space for conversation, characterised by empathic attention to each other in our evolving relationships.

The door remains open, and the kettle is on.

Dr Sandra Cullen

Assistant Professor of Religious Education, Dublin City University

Dr. Sandra Cullen is Assistant Professor of Religious Education at Dublin City University where she specialises in second-level religious education. As Director of the ICRE (Irish Centre for Religious Education) she supports research and teaching in religious education in a variety of contexts. She is the APF (Area of Professional Focus) leader for Religious Education on the Doctor of Education Programme at DCU, and serves on the Executive of EFTRE (the European Forum for Teachers of Religious Education) and on the International Advisory Board of the Journal of Religious Education.