Socioeconomic School Segregation: Differences Between Countries

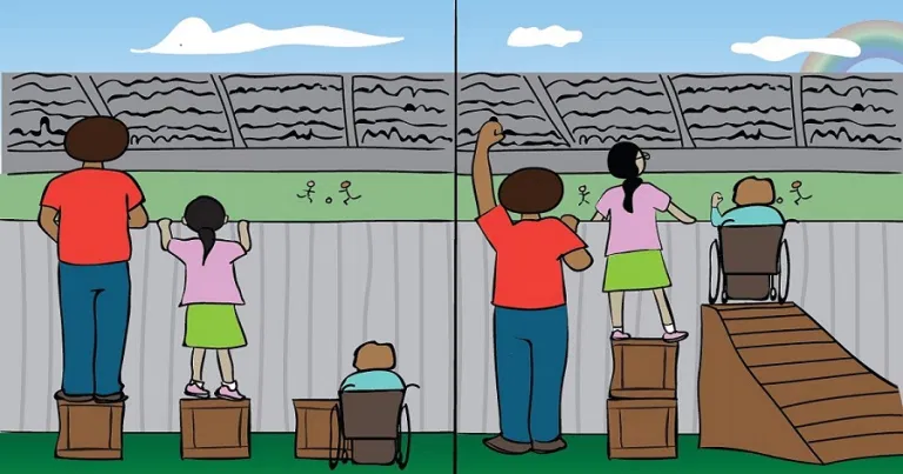

The segregation of students into different schools according to socioeconomic status, ethnicity and migration status is a substantial social problem in many countries. This can often lead to the provision of differing learning opportunities to students according to family background. School segregation can lead to national schooling systems strengthening intergenerational social inequalities. Such schooling systems present challenges to social cohesion and the individual development of students.

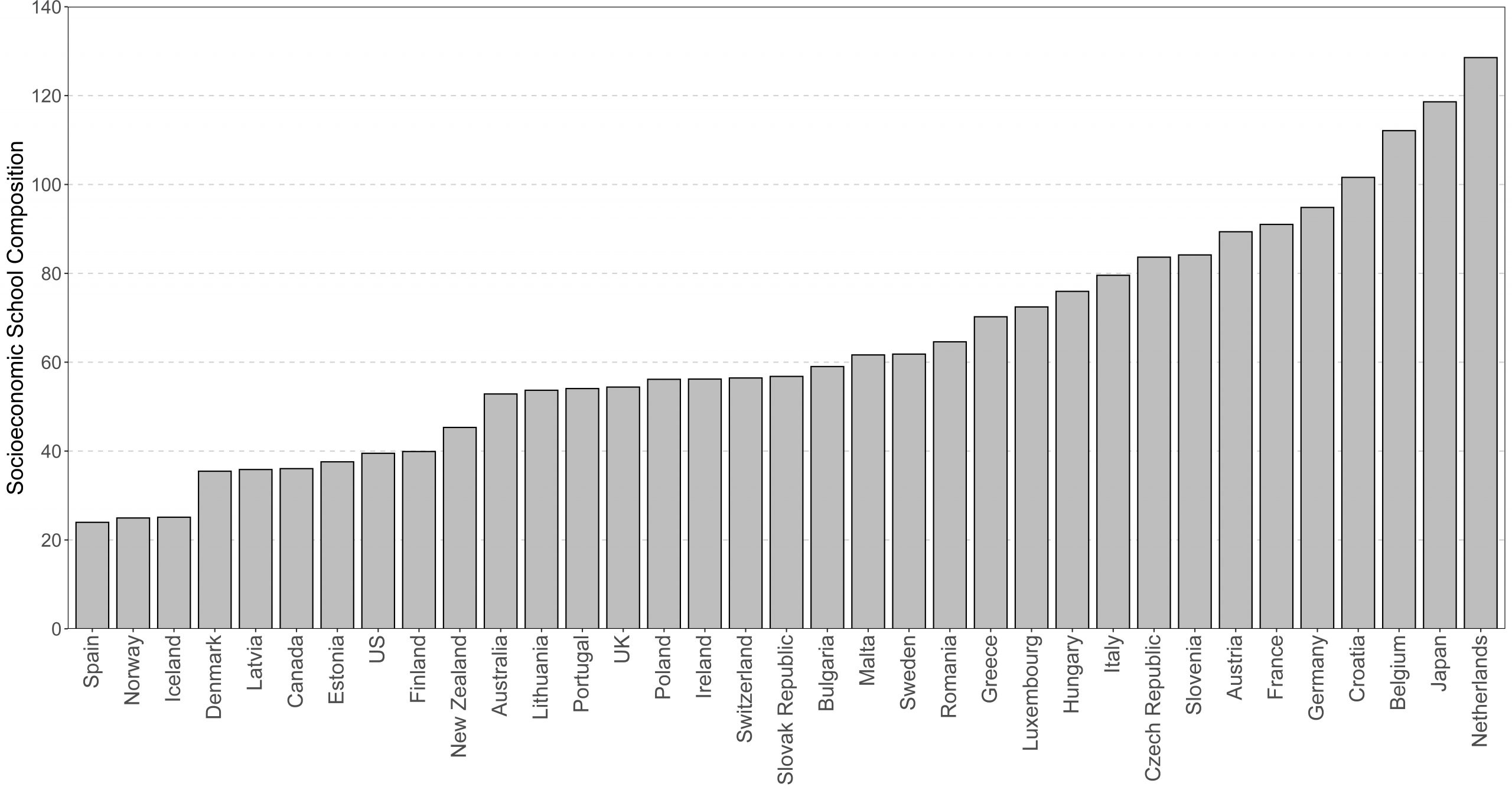

An outcome of socioeconomic school segregation is disparities between the socioeconomic composition of schools, or average school socioeconomic status, within national schooling systems. Researchers have found that socioeconomic school composition predicts achievement growth, university enrolment and social cohesion. International large-scale assessments such as the Programme for International Student Assessment have found that the relationship between school composition and academic achievement differs between countries. This suggests that policy differences between national schooling systems may predict international differences in the influence of school segregation on student learning.

Policy Settings Associated with Socioeconomic Compositional Effects

Research has associated tracking, academic selection, school competition and the private provision of schooling as potential causes of segregation, which in turn may predict international differences in compositional effects. Tracked schooling systems allocate students to curriculum streams that differ by emphasis on academic or vocational curriculum. Such systems tend to segregate students as academic schools are likely to enrol students from advantaged backgrounds, whereas vocational schools are likely to enrol students from disadvantaged families. This is unlike comprehensive schooling systems that offer a common academic and vocational curriculum across the majority of schools.

Academic selection also exists in some comprehensive schooling systems. In such systems, a minority of schools enrol the highest achievers in academic selection tests. Academic selection is associated with segregation as entry tests tend to favour students from advantaged family backgrounds, and advantaged families are more likely to pursue access to selective programs.

School competition or choice policies tend to segregate students as parents may seek to enrol their children in schools with peers of a similar social background, and higher-income families tend to have a greater capacity to exploit the benefits of school choice. Government subsidies to private schools may increase school choice to middle-class families, resulting in the socioeconomic residualisation of public schools.

Current research

International differences in school composition effects: PISA 2018 (Reading).

Our research examined these policy settings and found that tracking age, and the proportion of students attending public schools, partially explained differences in the socioeconomic compositional effect between developed countries (as defined by the United Nations). We found that countries that delayed the age at which tracking decisions are made, and those with a high proportion of students in public schools, tended to have lower school compositional effects.

The compositional effect tended to be smallest among Nordic and Baltic countries, which also tend to delay tracking to post-compulsory school-age and have minimal private provision of schooling. Among English-speaking countries, all of which have comprehensive secondary schooling systems, those with higher proportions of private school enrolments had stronger compositional effects. For example, Australia has a high proportion of secondary school students enrolled in private schools. Australian private schools receive substantial public funding whilst still charging fees. Our research has associated this policy setting with higher levels of compositional effects compared to Canada and the US which have much lower rates of private school enrolment.

Tracked European schooling systems tended to have sizeable compositional effects, being up to five times the size of Nordic countries. The Netherlands exhibited the largest compositional effect, which was associated with a substantial proportion of students in private schools and a tracking age of 12. In general, among European countries, those with earlier ages at which students are tracked tend to have higher compositional effects.

Policy responses

A number of policy reforms are suggested by this research to minimise systemic segregational effects. Schooling systems that have increased the age at which tracking takes place have improved the equity of academic outcomes. Further progress could be made in European schooling systems to minimise the socioeconomic segregation of students into differing curriculum streams, such as delaying the age of track selection or ensuring each track enables access to university study. In regards to comprehensive education systems, a reversal of school-choice policies, particularly among English-speaking countries, may lower school segregation effects towards levels in Nordic countries.

Key Messages

- The segregation of students into differing school types can lead to the provision of different learning opportunities.

- Socioeconomic compositional effects vary between countries and are associated with a range of student outcomes.

- Tracking, academic selection, school competition, and the private provision of schooling may explain international differences in the size of socioeconomic school compositional effects.

- Our research found that tracking age, and the proportion of students in private schools, predicted international differences in compositional effects.

- Compositional effects were lowest in Nordic and Baltic countries with no academic tracking and very small private school enrolment proportions.

- European countries with early tracking ages tended to have the largest compositional effects

Other blog posts on similar topics:

Michael Sciffer

Ph.D. student at Murdoch University, Perth, Australia

Michael Sciffer is a Ph.D. student at Murdoch University. His research interests are school segregation, compositional effects, interactions between social contexts and school effectiveness and the appropriate specification of statistical models.

References and Further Reading

Alegre, M.À., & Ferrer, G. (2010), School regimes and education equity: Some insights based on PISA 2006. British Educational Research Journal, 36(3), 433-461. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411920902989193

Ball, S. J., Bowe, R., & Gewirtz, S. (1996) School choice, social class and distinction: the realization of social advantage in education, Journal of Education Policy, 11(1), 89-112, doi: 10.1080/0268093960110105 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/0268093960110105

Bonal, X., Zancajo, A., & Scandurra, R. (2019). Residential segregation and school segregation of foreign students in Barcelona. Urban Studies, 56(15), 3251–3273. https://journals.sagepub.com/doi/abs/10.1177/0042098019863662

Brunello, G., & Checchi, D. (2007) Does school tracking affect equality of opportunity? New international evidence. Economic Policy, (22)52, 782–861. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0327.2007.00189.x

Chesters, J. (2019) Alleviating or exacerbating disadvantage: does school attended mediate the association between family background and educational attainment?, Journal of Education Policy, 34(3), 331-350, doi: 10.1080/02680939.2018.1488001 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02680939.2018.1488001?journalCode=tedp20

Dustmann, C. (2004). Parental background, secondary school track choice, and wages, Oxford Economic Papers, 56(2), 209–230. https://econpapers.repec.org/article/oupoxecpp/v_3a56_3ay_3a2004_3ai_3a2_3ap_3a209-230.htm

Jenkins, S. P., Micklewright, J. & Schnepf, S. V. (2008) Social segregation in secondary schools: how does England compare with other countries?, Oxford Review of Education, 34(1), 21-37, doi: 10.1080/03054980701542039 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03054980701542039

Kristen, C. (2008). Primary school choice and ethnic school segregation in German elementary schools. European Sociological Review, (24)4, 495–510, https://doi.org/10.1093/esr/jcn015

Martinez-Garrido, C., Siddiqui, N., & Gorard, S. (2020). Longitudinal Study of School Segregation by Socioeconomic Level in the United Kingdom. REICE. Iberoamerican Journal on Quality, Effectiveness and Change in Education, 18(4), 123–141. https://dro.dur.ac.uk/31783/

Meghir, C., & Palme, M. (2005). “Educational Reform, Ability, and Family Background.” American Economic Review, 95(1), 414-424. doi: 10.1257/0002828053828671 https://www.aeaweb.org/articles?id=10.1257/0002828053828671

Molina. A. & Lamb, S. (2022) School segregation, inequality and trust in institutions: evidence from Santiago, Comparative Education, 58(1), 72-90, doi: 10.1080/03050068.2021.1997025 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03050068.2021.1997025

OECD (2016), PISA 2015 Results (Volume I): Excellence and Equity in Education, PISA, OECD Publishing, Paris, doi.org/10.1787/9789264266490-en. https://www.oecd.org/publications/pisa-2015-results-volume-i-9789264266490-en.htm

Rumberger, R.W., & Palardy. G.J. (2005). “Does Segregation Still Matter? The Impact of Student Composition on Academic Achievement in High School.” Teachers College Record 107(9), 1999-2045. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ718513

Saporito, S. (2003). Private Choices, Public Consequences: Magnet School Choice and Segregation by Race and Poverty. Social Problems, 50(2), 181–203. https://doi.org/10.1525/sp.2003.50.2.181

Sciffer, M.G., Perry L.B., & McConney A. (2022). Does school socioeconomic composition matter more in some countries than others, and if so, why?, Comparative Education, 58(1), 37-51, doi: 10.1080/03050068.2021.2013045 https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/03050068.2021.2013045