The Effects of COVID-19 Lockdowns on Children’s Education

The theme of the ECER 2020 conference was Educational Research: (Re)connecting Communities. This focus was initially prompted by the concerns about the potential effects of Brexit and other fractures in communities in Europe. The conference aimed to interrogate the capacity of educational research to address the complexity of the challenges that are encountered in connecting and reconnecting communities in contemporary Europe.

The effects of Covid-19 and the consequent lockdowns that swept across Europe and the world led to further, more extensive, fractures and disconnects across Europe. Schools, universities and workplaces were closed. There were severe restrictions on travel and movement around Europe.

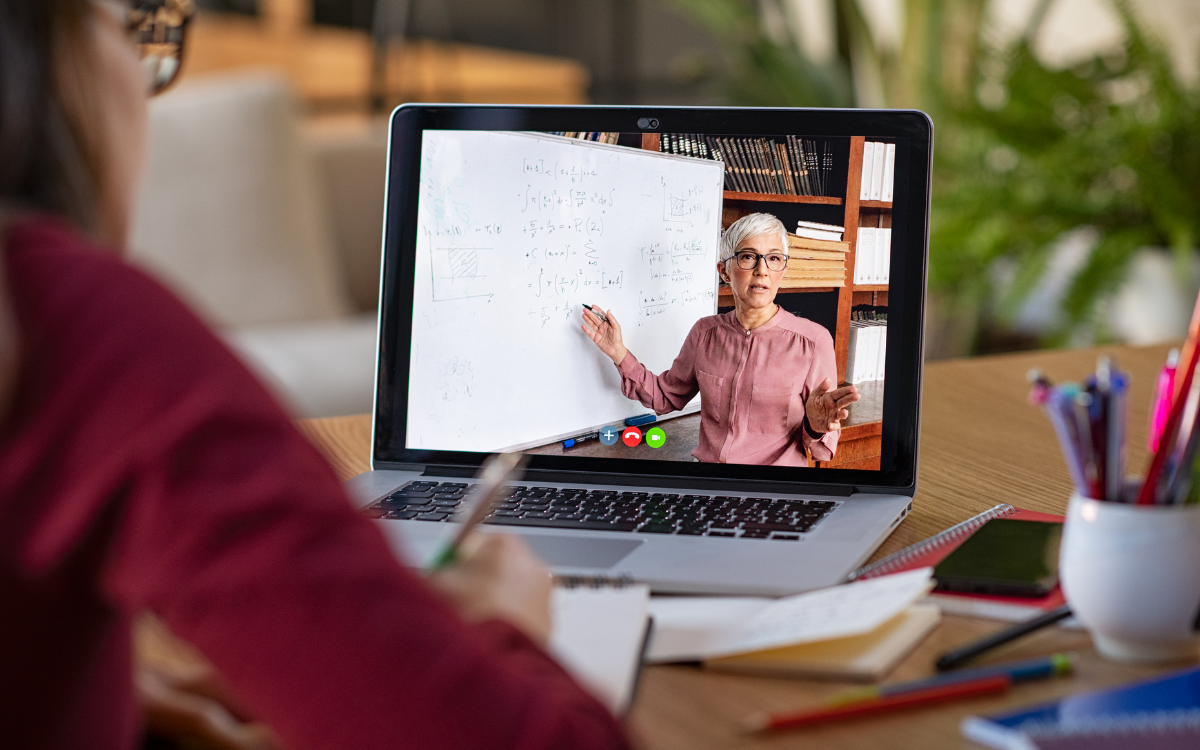

As the Covid-19 pandemic and the lockdowns continued, a number of serious issues arose for children and the continuation of their education in Scotland. For many children and young people, school became an online engagement with teachers. The use of platforms and materials and the frequency of contact varied across Scotland’s 32 local authorities with learning resources provided by schools, media companies and commercial companies.

The Effects of Home Schooling

Recent research indicates that the move to learning at home for the majority of pupils led to mixed results for pupils, parents and teachers. Some parents and carers became anxious about adopting a greatly enhanced role in supporting the formal education of their children in the home. The formal education of children is normally assumed, almost exclusively, by highly qualified professional teachers in a school setting. There were not always sufficient resources at home to support formal home learning.

The effects of digital poverty, or digital exclusion, became apparent as awareness grew that some families did not have adequate equipment or even access to the internet to support their children in online learning. Not all members of the teaching profession had the skill set for the sudden move to online teaching and learning and, like many other professionals, had to upskill. Further, all teachers had to spend a substantial amount of time preparing and implementing online learning. There was serious disruption to the exam diet for senior pupils and a highly publicised reconfiguration of assessment practices leading to a controversial recalculation of grades for the major public examinations.

All of this unfolded in the context of serious concerns about rising levels of child poverty pre-COVID-19 and further increases as a result of job losses during lockdown. This situation contributed to a rise in food insecurity for many families and more families now seek free school meals for their children and access food from foodbanks. The effects of the rising levels of child poverty will have consequences for the physical and mental health and well-being of the children and young people.

The New Normal

There are other ways to view the outcomes of the lockdowns. As we came out of lockdown and schools resumed, ‘The New Normal’ was a phrase that came into current use. An important aspect of ‘new normal’ is the new knowledge, which will inform any altered concept of normality. New knowledge can emerge through any number of activities, but typically, it is the result of sustained engagement with others, materials and contexts during which we come to assimilate the nuanced experiences and perspectives of others in a new way.

Positive Effects of the Lockdown for Learners

Children and young people will have had a range of experiences of lockdown. As a result, they will have developed new knowledge about themselves as learners. There are likely to be pupils who will have experienced ‘schoolwork’ differently in a positive way; who have engaged with their learning at their own pace and on their own terms. Some will have enjoyed working alone, whilst others might have benefited from engagement with siblings and parents.

Anecdotally, we have probably all heard of examples of children and young people learning new things and developing skills and interests not directly connected to schoolwork. They have already blended their own ways of organising and engaging with their learning, their own interests and other people with whom they have interacted during this period.

The likelihood is that all young people will have learned new things and have a stronger sense of themselves as people and learners. It is important that this new knowledge is sought out, recognised and built on as our children, young people and schools return. We are in a unique situation and should take the opportunity to engage children’s and young people’s new skills, newly-realised abilities and personal interests. We should blend these insights into practice and pedagogy in schools as we simultaneously explore new ways to allow them to demonstrate their learning.

Positive Effects of the Lockdown for Teachers

Teachers will have learned new things about themselves, their colleagues and the children and young people with whom they work and the relationships among them. Teachers know that young people’s emotional experience of learning is as important as their cognitive experience. The current situation presents a unique stimulus for teachers to make sense of the relationships they have with each of their pupils.

Teachers already see their pupils as learners and not simply people who have to be taught. They will already be aware of pupils’ skills abilities and interests, and the new experiences which young people bring to school could be used to enhance and enrich the learning of all young people. Teachers’ interactions with pupils during lockdown will have enriched their own sense of themselves as teachers and their place in the lives of their charges. This new knowledge will help reinforce any new sense that pupils have of themselves as learners and teachers have of themselves as teachers.

EERA also has a role to play, and the recent online events had a significant role in reconnecting our research communities. The events provided new spaces in which education was explored, theorised and researched from the perspectives of all member associations and networks. EERA also has a role in generating the new knowledge that will increasingly and relentlessly nudge forward our understanding of education.

Professor Stephen J. McKinney

Professor, School of Education, University of Glasgow

Stephen J. McKinney is a Professor in the School of Education, University of Glasgow. He leads the research and teaching group, Pedagogy, Praxis and Faith. He is the past President of the Scottish Educational Research Association. He is on the Editorial Board of the Journal of Beliefs and Values, Improving Schools, the Scottish Educational Review. He is a visiting professor in Catholic Education at Newman University, an Associate of the Irish Institute for Catholic Studies and on the steering group for the Network for Researchers in Catholic Education. He is a member of the European Educational Research Association Council. He is the Chair of the Board of Directors of the London School of Management Education. His research interests include Catholic schools and faith schools, the impact of poverty on education and education and social justice and he has published widely on all of these topics.

Dr George Head

Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the School of Education, University of Glasgow

George Head is Honorary Senior Research Fellow at the School of Education, University of Glasgow, Scotland. George is a past-president of the Scottish Educational Research Association (SERA) and has represented the association on the European Educational Research Association (EERA) Council and served as Senior Mentor to the EERA Emerging Researchers Group. He is a visiting professor at Newman University, Birmingham. His areas of academic interest include Inclusive Education and the learning and teaching of young people whose behaviour schools find difficult. George was a member of the Local Organising Committee for ECER 2020 which was scheduled to take place in Glasgow